Changi - Singapore & POW Leadership

Changi – Singapore & POW Leadership

Changi was at the north-eastern tip of Singapore Island, about 11 miles from city centre. An important British Garrison with large blocks of garrisons and workshops, fine European houses and flats for married quarters, beautifully kept gardens, lawns and playing fields and a native village of Chinese and Indian shops and houses.

Above Changi Camp

‘For much of its existence Changi was not one camp but a collection of up to seven prisoner-of-war (POW) and internee camps, occupying approx. 25 square kilometres. Its name came from the peninsula on which it stood, at the east end of Singapore Island. Prior to the war the Changi Peninsula had been the British Army’s principal base area in Singapore. As a result the site boasted an extensive and well-constructed military infrastructure, including three major barracks – Selarang, Roberts and Kitchener – as well as many other smaller camps. Singapore’s civilian prison, Changi Gaol, was also on the peninsula.’

Constructed in 1936 , Changi Gaol was at that time declared as one, if not the best prison camp throughout the British Empire.

Two days after the Surrender at Singapore 17 Feb 1942, Allied troops were ordered to gather all the food and clothing they could carry and march to Changi – the former British garrison of about 25 square kilometres on the north-eastern tip of the island. Changi’s infrastructure included three major barracks each 3 stories high, several smaller groups of buildings, large numbers of bungalows for officers, married officers and administrative staff. There were large parade grounds and playing fields, churches, canteens, theatres and cinemas, tennis and squash courts, swimming pools, bathing beaches and even yacht clubs.

‘Also located in the Changi area was Singapore’s forbidding civilian prison, Changi Gaol, which had been modelled on New York’s Sing Sing prison. This prison, which was designed to hold 600 prisoners, was initially used by the Japanese to house some three and a half thousand civilian internees. Two years later, as the POW population declined to about 12,000, the internees were moved to a nearby camp at Sime Road, and the remaining POWs were moved into the Changi Gaol where they were crammed into the gaol cells, as well as into atap huts that they built in the prison grounds. As several men were housed in a cell designed for one, with a single concrete bed in the centre, and with airflow severely restricted, to be located in a hut outside was far preferable’

CHANGI POW CAMP opened after Fall of Singapore 15 February 1942. It was main camp for captured British and Commonwealth Forces, including Australians.

Changi Prisoner of War Camp contained most of the Australians captured in Singapore on 15 February 1942. They occupied Selarang Barracks, which remained the AIF Camp at Changi until June 1944 when they were moved to Changi Gaol.

The gaol was built to hold a maximum of 600 prisoners.

In February 1942 3,000 civilians were housed in the Changi Gaol.

The POWs trudged past Changi Gaol from the city on their first humiliating march after surrender. The men noted the austere gaol exterior and iron grills, thinking they were pleased not to be staying there and they passed by to Selarang.

During the next years POWs were catch glimpses of the civilians, or even hear women’s voices.

At the Conference House in Changi Gaol the Japanese held court and issued their decrees to Allied Staff Officers to impart to POWs. This became the ‘battleground’ for Allied Officers to fight successive Japanese Generals – Fukue, Arimura and Saito in their unremitting struggle for better conditions.

If a special conference was called, the official party, protected by carrying a flag, would march down the winding road while the Camp waited.

Was it another work party for Thailand, an execution or another concentration in Barrack Square? Nobody would know until the officers returned from the Gaol – the seat of all infamy!

In October 1944, the Japanese unexpectedly ordered the Australian POWs move into Changi Gaol.

All 7,000 POWs within one month! The civilians were moved elsewhere.

The POWs remained in very overcrowded conditions until the end of war.

Many POWs lived in attap huts built outside the Gaol wall. Murray Cheyne mentions this in his memoirs.

‘A concert party of prisoners entertained fellow detainees on a regular basis until this was stopped by the Japanese guards towards the end of the war. Guards occasionally attended these concerts, and their presence often meant that subject matter would have to be censored. The Japanese surrender saw many POWs from working camps return to Changi to recover before being returned home.’

The building was damaged by bombing was finally demolished in 2000.

__________

Changi was one of the least brutal Japanese POW camps, particularly compared to those on Burma–Thailand railway.

Changi tended to be a transit camp for many prisoners who were shipped out on working parties to Japan, Thailand and Burma. POWs sailed from Java to Singapore on their journey to Burma-Thai Railway whether to be entrained to Thailand or sail onwards to Burma.

With various work parties departing Singapore for the Burma-Thai Railway during 1942 & 1943 and further work parties sent to Borneo and Japan – the number of POWs at Changi fell to less than 2500 men. These men were mostly disabled by illness or from battle injuries. There also remained a large contingency of POWs involved in essential services The administrative HQ of 8th Division continued, but had lost more than 80% of its personnel.

When the railway was completed by the end of 1943, some POW Work Forces such as ‘F’ and ‘H’, returned to Changi.

For POWs who left Changi – conditions there were far superior and life much easier than anywhere else. Changi seemed to them now like a holiday camp!

POWs at Changi rarely saw a Japanese guard/soldier – unless on work parties.

Many deaths at Changi occurred because of events elsewhere – men who had been wounded in fighting 1941-42 and debilitated POWs who returned from work parties off Singapore Island.

Changi was a prison of confinement, deprivation and severe malnutrition, but it was never a camp of brutality or frequent deaths. Because of the fluctuating numbers in Changi—from a total of 45,000 Allied prisoners to 5359—it is difficult to work out the exact death rate.

POWs who left Singapore with Work Parties now worked like slaves, were starved, beaten, humiliated and knew they had to survive the sadistic and brutal Japanese guards and endless unknown tropical illnesses for which they had no medicines if they were ever to survive and return home to Australia.

Those POWs in Changi who volunteered for work parties did so generally from optimism and out of boredom – hoping food and conditions would be better! Opportunists always sought ways and means of pilfering who knows what? Something to eat, something to trade.

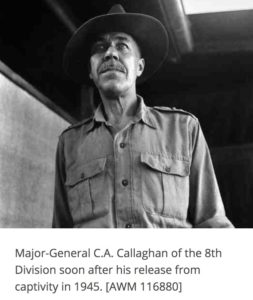

General Percival GOC Malaya, Major-General Cecil Arthur Callaghan Commander AIF and General Overaker of Netherlands East Indies departed Changi on 16 Aug 1942 for Japan and thence interned on Formosa until October 1944 when they were moved to Japanese held Manchuria until the end of war. They were released by American Forces.

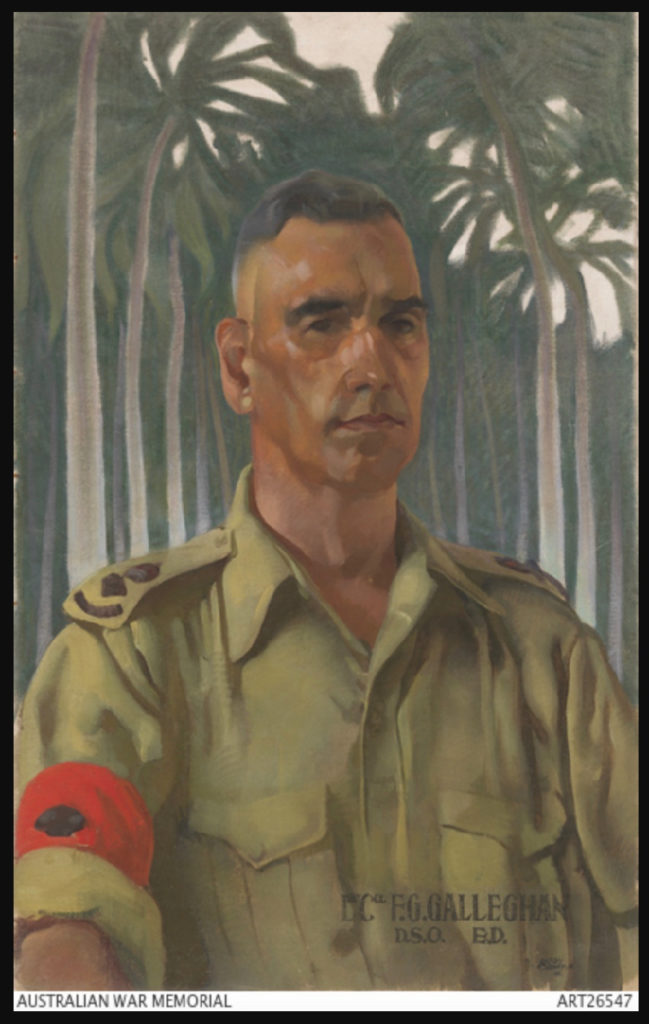

Lt. Col. (Black Jack) Frederick Gallagher Galleghan was appointed Commander of AIF in Singapore on Major-General’s departure.

Major General Cecil Arthur Callaghan CB, CMG, DSO, VD (31 July 1890 – 1 January 1967) who served during First and Second World Wars. He was commander of 8th Division when it surrendered to the Japanese Empire at the end of Battle of Singapore. He spent the wars years in captivity in formosa and Manchuria.

Major General Sir Frederick Gallagher Galleghan, a senior officer in Australian Army who served in First and Second World Wars was appointed Commander of AIF, Singapore.

Galleghan was born on 11 January 1897 Jesmond, a suburb of Newcastle, NSW. Of West Indian extraction, his dark complexion would in later life lead to his nickname of ‘Black Jack’.

In October 1940, Galleghan was appointed commander of newly formed 2/30th Battalion, part of 27th Brigade and originally destined for service in Middle East with 9th Division. However, the following month, the brigade and Galleghan’s battalion with it, was transferred to 8th Division.

Galleghan, a strict disciplinarian, had high expectations of his battalion and accordingly implemented a rigorous training program. The battalion would become known as ‘Galleghan’s greyhounds’ and was initially based at Tamworth but in the coming months would move around various bases in NSW. Training carried on into 1941 and in July the battalion embarked for Singapore on Dutch transport Johan Van Oldenbarnevelt.

In later years he was criticised for his very strict discipline at Changi and today, his leadership style is questioned by others.

Calleghan clashed with several officers, including Weary Dunlop and ‘Roaring Reggie’ Newton when they were in Singapore from Java before entraining to Thailand.

Looking back it can be said Changi accommodated officers who were from time to time, were involved in petty jealousies – particularly those who remained in Singapore throughout the entire war – and there were many!

Leadership of POWs was vastly different to leadership in the field. Not all officers adapted to their newfound status.

Please read further about POW Leadership

In particular, look at Pages 80, 81.

Also please read this Training and Leadership in the 2nd AIF: a case study of Brigadier F.G. Galleghan.

Please read Tom Bunning’s diary description of the last weeks at Changi prior to Japan’s surrender.

Below: Released Changi POWs 13 Sep 1945 being evacuated on the first ship to arrive in Singapore – patients awaiting to board MV ‘Manunda’ at Singapore after the end of the war – waiting to return home to Australia.

Above: Hospital Ship MV Manunda.

Above: Hospital Ship MV Manunda.