Omuta – Just when you think you have read the worst about POW Camps…

Just when you think you have learned or read the worst story or stories about POWs – illnesses they suffered, tropical ulcers which destroyed limbs, bashings they endured, deaths of mates, the stench and fifth they lay amongst, the months and years of hoping ……the terrifying sea journey wondering if they would live to see another day – these men arrived to work at Mitsui Omuta, Japan.

Omuta Camp 17

Bay of Omuta about 17 miles northwest of Kumamoto & 40 miles south of city Fukuoka as was liberated 2 Sep 1945.

The mine was ruled by Mitsui, the camp was ruled by IJA and finally there was the American mafia to deal with. They all used brutality beyond our comprehension.

The Australian POWs had to quickly learn that honesty and spirit of comradeship which existed in Singapore and on the railway did not exist at Omuta. Thieving, cheating and racketeering was the way of life. Wet clothes could never be hung to dry out unless you watched over them. The same for food and utensils in the mess hall.

The American mafia was in fact a group known as the Democrats run by Lt. Edward Little of the US Navy who ran the Mess Hall and Sgt Bennett who was in charge of Omuta Camp Duties.

Starving men traded anything and illegal food trading took up much of camp routine.

Corporal Billy Alvin Ayers, 4th Material Squadron 1942 Bombardment Group, US Army Air Corps wrote in his Affidavit:

“Bennett and Little made every effort to win favour of the Japanese prison authorities”

“The two Americans would report minor infractions of Omuta’s fierce rules to the Japanese, causing POWs to suffer severe discipline by the Japanese.”

This was quite probably the real home of ‘King Rat”.

Lt. Little was court-marshalled after the war, however this is little compensation for the misery for which he and his thug mates were responsible. It is not possible to bring back limbs, health or life.

The above information has been gathered from several sources including:

‘No Time for Geishas’ by G.P Adams, Corgi, London 1973

‘On Paths of Ash’ by Robert Holman edited by Peter Thomson, Pier 9, Murdoch Books P/L, NSW 2009.

‘Slaves of the Son of Heaven’ by Roy Whitecross, Kangaroo Press, 2000.

To read further about Omuta Camp No. 17, please look up camps.

And read Hambley’s Affidavit whilst POW Omuta

And Kranostein’s Omuta Camp Affidavit.

For some men the thought of being crushed by collapsing ceilings, suffocation and/or blast injuries were very real at the Omuta Mines. Others simply feared working in a confined space. Apprehension was dealt with the usual Japanese method of persuasion and brutality. It is known some Dutch and Americans deliberately injured themselves (such as breaking an arm) to avoid mine work. Who can blame them. The working hours were constant, work, sleep, work. They had some time about once monthly for themselves. With travel to and from the mines their work day was 12 hours or more.

WX16727 ‘Lou’ Lonsdale who arrived with ‘Aramis’ Party 19 June 1944 describes working underground in his Affidavit to War Trials. (AWM54 File 1010/4/92)

‘We were worked 8 or 9 hours a day on shift work in the mine and were actually away from camp about 12 hours because we had to march about two miles to the mine and back again. Work in the mine was divided into three sections.

-

Work in the extraction section consisted of blasting the coal wall and shovelling coal into trucks and elevators to the surface.

-

In the preparation section work consisted of building rock walls along the tunnels as coal was being taken out, to make it as safe as possible.

In the exploration section work consisted of tunnelling through from given points making new laterals and coal.

Japanese and Koreans were working in the mine at same time as the POWs and Chinese labour battalions worked in the adjoining mine, which connected with the mine we were working in. Reports came to us that the Americans had originally owned the mine and abandoned it as they considered it unsafe to extract more coal. When we arrived at Omuta we found the mine had been re-opened. We were taking out pillars of coal that should have been left there for safety measures. In some parts of the mine laterals had sunk so low we were bent almost double while carrying tools such as jack hammers, shovels, picks etc. and heavy logs for timbering. There were quite a lot of falls of coal and rock. Ironically the Japanese suffered most in these falls’.

Joe Starcevich WX8758 had his left leg injured in a rock fall on 5 Jan 1945 while working underground at Omuta.

More than 50 years later his leg was amputated.

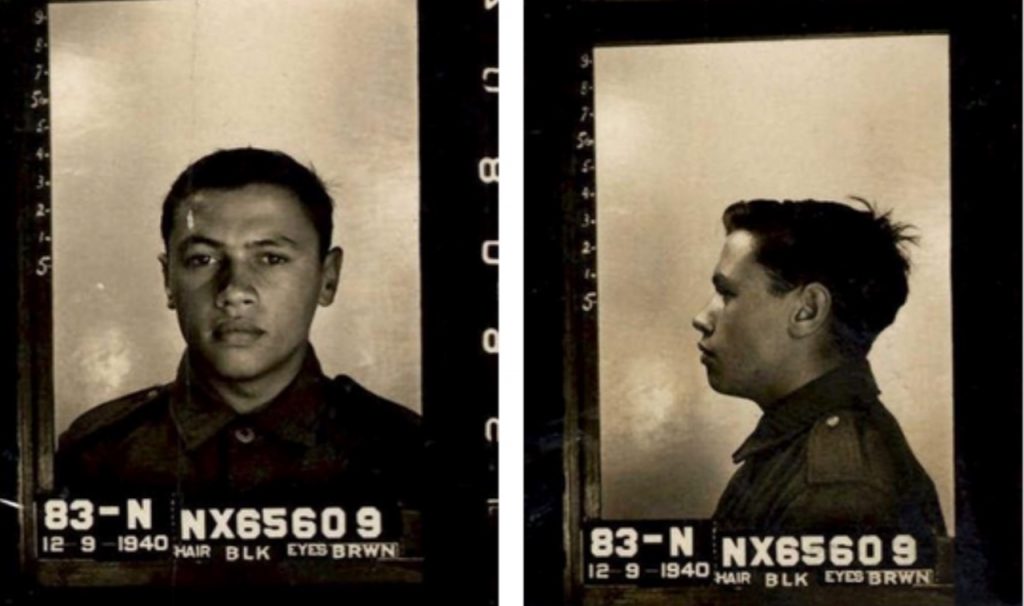

Above Krasnostein

Please read Krasnostein’s Affadavit

You can also read Wilke’s Affadavit

You can read further about Omuta

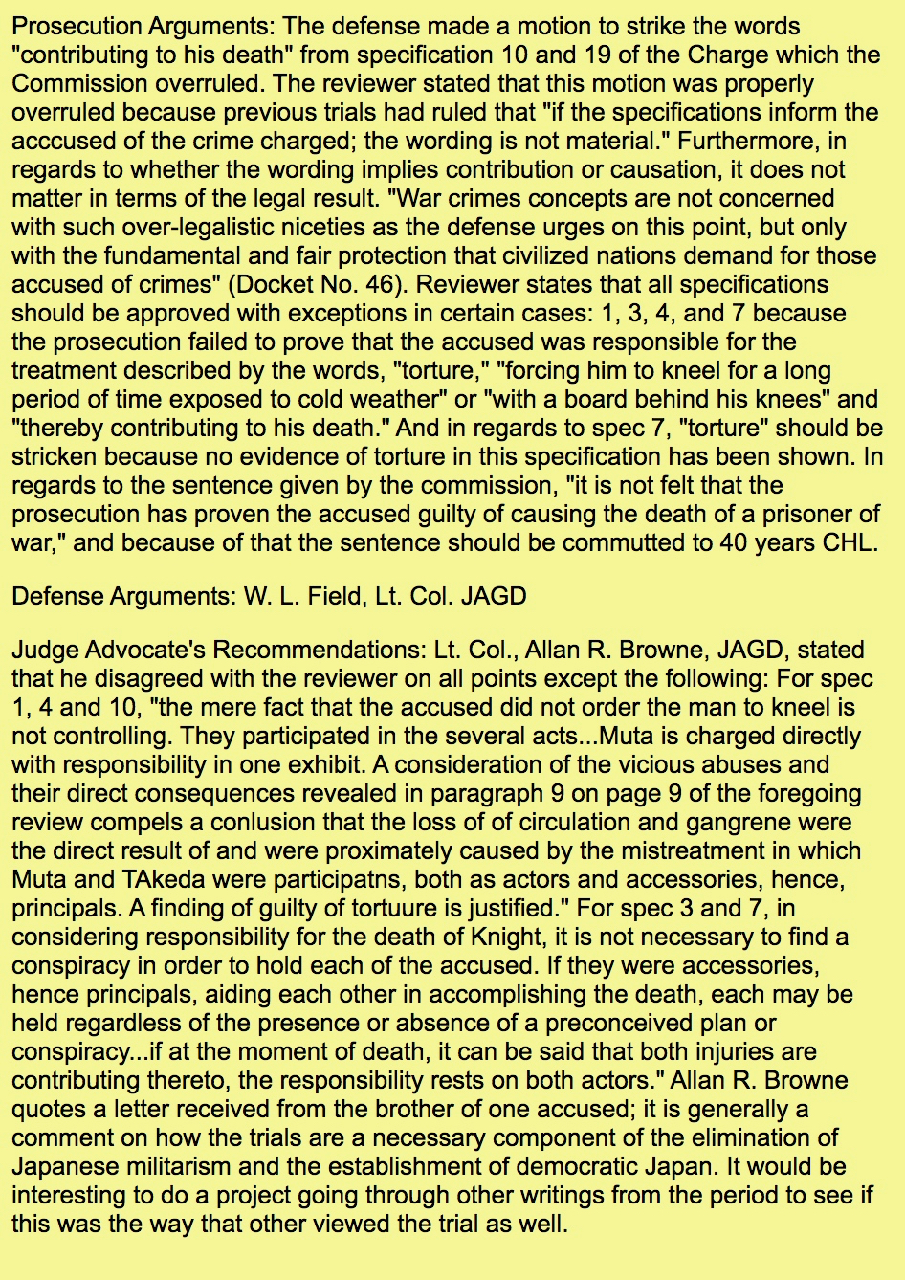

MORTALITY

Dec. 1978,

DAI JU NANA BUNSHO [CAMP #17]

NIGHTMARE REVISITED

by THOMAS H. HEWLETT, M.D., F.A.C.S., COL. U.S.A. (Ret)

Our mortality is recorded, and I might comment that it is lower than Dr. Proff and I predicted it might be after our first two months in Camp 17. One hundred twenty-six men died in the 2-year period; 48 deaths attributed to pneumonia, 35 to deficiency diseases, 14 to colitis, 8 to injuries, 5 to executions, 6 to tuberculosis, and 10 to miscellaneous diseases.

MORTALITY RATE (in percentage points)

Total population 1859 (126) 6.7%

American 821 (49) 5.9%

Australian 562 (19) 3.3%

British 218 (17) 7.7%

Dutch 258 (41) 4.2%

(“A” 500 (21) 4.2%)

What has just been presented to you is not documented elsewhere in the medical annals of this country, the proverbial land of plenty. Certainly no human would knowingly submit to a controlled laboratory study aimed at duplicating this experience. I believe, along with Dr. Jacobs, that we survivors still face disabling physical and emotional problems which can be traced to our experience. Medical computers and the young physicians of the V.A. are, I believe, completely confused when called upon to evaluate our problems. Medicine is not an exact science — it has chosen to deem the profession an art and a science. Our hope must then lie with those physicians who evidence art in dealing with the whole patient.

There is no summary to a nightmare that was permanently tattooed in our brains, but that is how it was for those who were “expended”…..

We wish acknowledge and thank the Mansell website for above information. Please read further

Please listen to a AWM recording/interview with Australian POW David Runge, Driver with AASWC, 8th Division who was at Omuta Camp

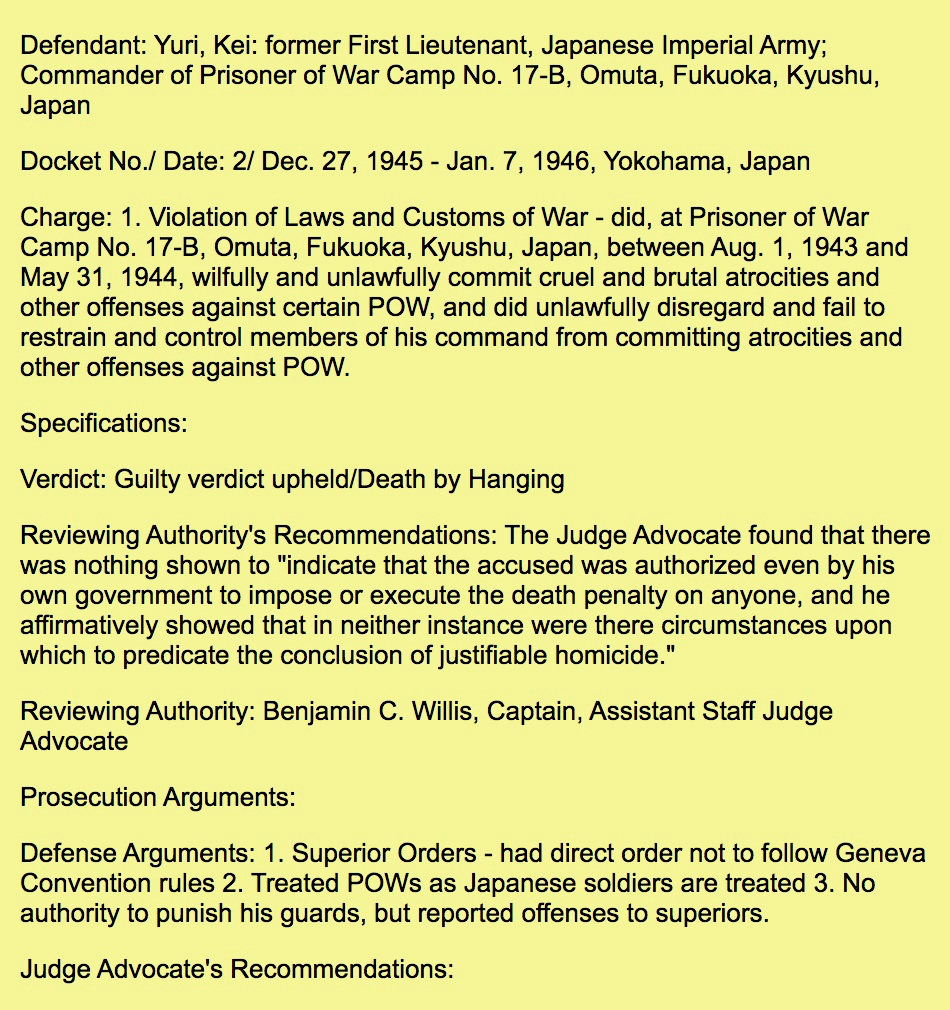

Runge was tortured, forced to kneel for days in snow. Dr. Duncan had to amputate legs below the knees. Guards carried legs around laughing. Documented in Whitecross’s excellent book, Slaves of the Son of Heaven. Published in 1951, the book mentions many names and incidents from Camp 17.

Below: Runge

Above: Runge being carried off his transport ship back to Australia, 1945.

‘The worst cases I saw were an American NCO Johnsen or Jones (something like that) who got a beating in front of the guardhouse with a rod or something of the kind, because he wore his US Army cap. The beating (we saw it from our barrack) was so bad that he died the next day.

In another case an Australian who took a nap in the coal mine and fell asleep, without warning his other companions; so at the roll call outside he was missing. After we were back in the camp again he had woken up and reported to the guards of the other shift. The Japs considered this as an effort to escape and was punished by kneeling in front of the guardhouse with a bamboo stick between his knees and calves on his legs during the whole night in wintertime. The result was quite evident.’

______________________

Below are two condensed versions of Little and Bennett’s US Naval Court Martial which I have copied so you read something of what life was like for the POWs at Omuta. (Cheryl Mellor, 2/4th MGB Historian 8 March 2022 – I wish to acknowledge the sources)

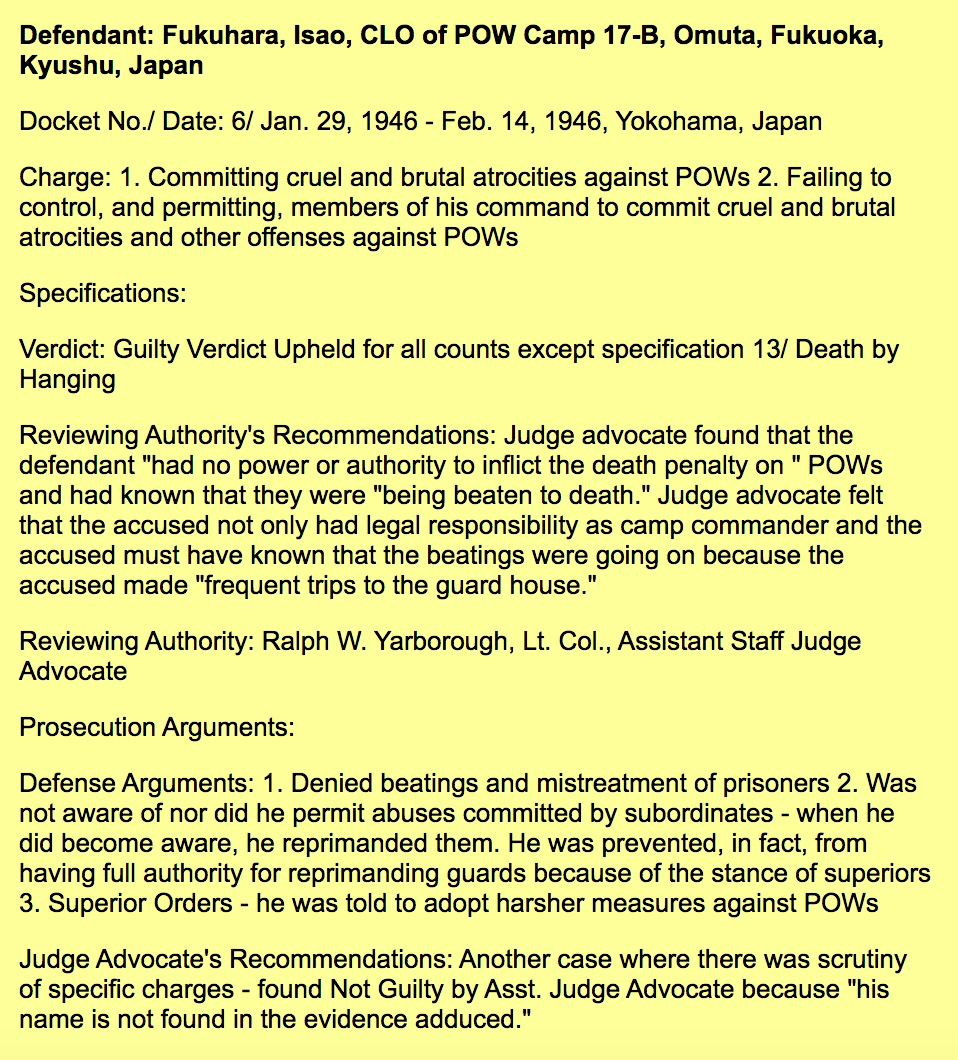

THE US NAVEL COURT MARSHALL OF LT COMMANDER LITTLE, IN CHARGE OF MESS HALL and T/SGT BENNETT, IN CHARGE OF CAMP DUTY – OMUTA CAMP, JAPAN

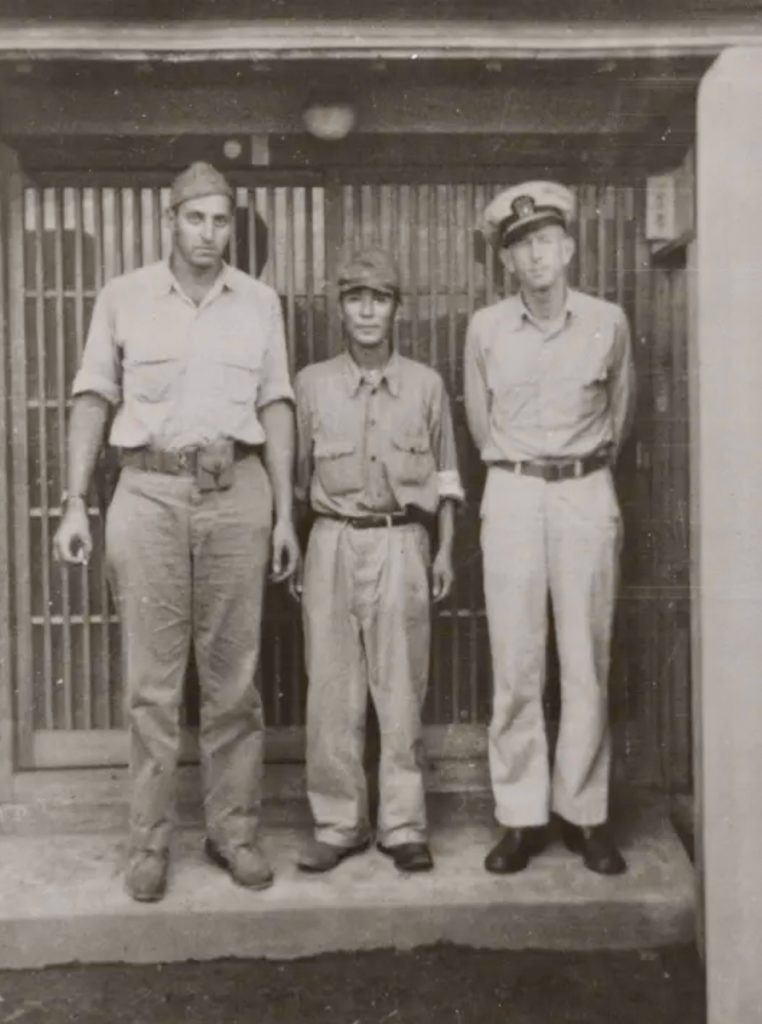

Above: Little is on right, guarding Kunimitsu Yamauchi – civilian interpreter with Mitsui Mining – later sentenced to 33 years fo his treatment of POWs. (Dec 1945)

The court heard of the shocking torture by Japanese of POWs – with electric currents. 1st Lt. Fukahara, Commander of Omuta Camp forced prisoners to hold iron bars in each hand which were about 8” long and 1” diameter. These bars were attached to electric current of approximately 100 volts. Water would be poured on the bars and the power turned on. Prisoners became unconscious for about 10 minutes then regain consciousness. This was repeated every two hours for a period of several days. Cold water was poured over the prisoner’s clothing and not permitted to dry out.

The Court placed some of the blame on Little and Bennett who collaborated with Japanese authorities by reporting infractions of rules rather than dealing with them in their own way.

One of the most gruesome events was the starving to death of Corporal James Pavlockus of the US Marine Corps (captured Philippines). Little of California, was being tried with Decatur for turning Pavlokus over to the Japanese.

Chicago- born Pavlockus of Greek descent, was unruly and difficult to discipline. He had a great fighting record as a member if 4th Shanghai Marine Regiment. According to Samuel Schulman of Brooklyn, who has preferred charges against Little, Little came over to Wise’s table and asked “Where did you get that rice?”

“From a friend” Wise replied .

“Don’t lie to me” Schulman quotes Little as saying. “You got it from the Greek for two and half Yen.”

Wise admitted this was the fact.

According to a Sworn Affidavit by Wiilie Reem of Gilbert, La:

Little turned Pavlockus over to the Jap authorities. “He was placed on solitary of rice and water for 30 days. The next 8 days his water was taken away. His rice ration consisted of one ¼ canteen cup per day. Pavlockus died on the 38th day of his solitary sentence, and was cremated in a nearby town.”

“I spoke to him on three occasions the last time was on his 25th day of confinement. He was pretty well gone by then. He had to hold onto the wall to get to me where I was standing in an open space. Little was responsible for this man’s death. Marine Sergeant Joe Dudley asked Lieutenant Little why he had turned Pavlockus over to the Japs and Lieutenant Little said if he had to do it over again, he would”.

Schulman states that other prisoners tried to throw food over the wall to Pavlockus, but the Japs saw to it that this was stopped. Major Thomas Hewlitt of New Albany, Indiana, senior medical officer who examined the body, said that Pavlokus’ weight was reduced from about 175 to 55 lbs. Schulman stated that Pavlockus was so thin and being a tall man his body was too long for a Japanese coffin and folded in half.

According to Schulman, Pavlockus though unruly, had a heart of gold and if he had extra food he would share it with other men. Schulman said Pavlockus had a previous row with Little for which he was turned over to the Japs. The latter said if they caught him again they would kill him.

Although secrecy shrouded the court martial trying Little, it was believed he was not being charged with the death of Pavlockus or Private William Knight of New York, who was also starved and beaten the death.

One charge against Little was for slugging Schulman in the mess hall and threatening him with words “You are standing on the brink of death”.

Schulman stated that before any threat could be carried out, Major Robert Schott, then Camp Commander, intervened.

Apparently Little incurred the hatred of every enlisted man and officer amongst the 1700 American, Australian, Dutch and English POWs interred at Omuta. One officer remarked he was amongst the last of the 1700 liberated POWs to pass before the American examiners of war crimes, to whom statements were made regarding Japanese war guilt. The examiners remarked:

“You don’t need to tell us about Little. Every man before you has made a statement about him.”

One insight into the prisoner’s attitude towards Little is given by Donald D. Rutter, former US Navy radioman of Michigan who wrote this columnist the following:

“What has happened to the testimony of 1700 American, Australian, Dutch and English POWs that were under him hated him as much as they ever hated a Japanese – and for a good reason:

“My legs today have no reflexes because of Little – who turned me in for stealing a little rice.”

“Little stole – and it was our Red Cross supplies, otherwise how did he drink American coffee all the time, eat spam and smoke American cigarettes. His henchmen traded our ration of rice to us for the little we had. He was merciless and as cruel a dictator as Hitler ever was. He was even hated by the officers in our camp. We feared him as we feared the Japs.”

“Knight and other POWs caused trouble by stealing, but when Major Manerow was in charge, he handled the situation without turning our boys over to the Japs to torture and kill”.

On my mess kit are words inscribed in Japanese I will long remember as meaning nothing but pain and harshness”. On the bottom of my mess kit is the sentence in American ‘Get out of my mess hall’. These are Little’s famous, or more rightly infamous words he used often. Those words I will remember always. Words of hate in the hearts of all men who knew him in Camp 17-B, Omuta, Fukioka, Japan”. (1947)

Pavlockus had obtained two bowls of rice from a Japanese soldier and sold one to fellow POW Stephen Wise in the American mess hall.

A Naval Court Marshall in Washington tried Commander Little, Omuta POW Camp, Japan in strict secrecy. Court witnesses were lectured they were not to talk to anyone about their testimony. All the while, the Japanese public had complete access to all the facts.

In a Sworn Affidavit from fellow American POW Billie G Ayers presented to the court stated Lt. Little handed over fellow POWs for punishment to Japanese guards.

Omuta Camp Conditions

The barrack comprised 33 one-story buildings, 120′ x 16′, with ten rooms to a barrack, of wood construction with tight tar paper roofs. More barracks were built a more prisoners arrived. Ventilation was satisfactory. Three to four officers were billeted in one room, 9′ x 10′. No heating facilities, and while the climate was mild, it must be remembered that the men were sensitive to temperatures around 50 degrees F, and because of their weakened condition due to malnutrition, the dampness and cold were very penetrating. The barracks were light enough during the day without artificial illumination. Each room had one 15-watt light bulb.

Air raid shelters were dug into the earth about 6′ deep and 8′ wide, 120′ in length, timbered in similar manner, to coal mines, covered with 3′ of slag and an adequate splinter-proof roof.

During the bombardment in June 1945 two of our barracks — one of them was my housing — were hit and burned down; the occupants of these two barracks had to sleep with one blanket on the tables at the far end of the mess hall till the day we were evacuated! Luckily the occupants of the two barracks worked in separated mine-shifts.

The beds consisted of tissue paper and cotton batting covered with a cotton pad 5’8″ long and 2′ 6″ wide. Three heavy cotton blankets were issued by the Japanese in addition to a comforter made of tissue paper, scrap rags and scrap cotton.

(b) latrines. In each of the 33 buildings, and at the end thereof, were three stools raised from the floor about 1.5 feet on a hollow brick pedestal, each being covered with a detachable wood seat, and one urinal. A concrete tank was underneath each stool. The prisoners made wood covers for each of the stools, thereby reducing the fly nuisance. The offal in the tanks were removed by the Japanese laborers each week.

bathing. The bathing facilities were in a separate building equipped with two tanks (shown above) approximately 30′ x 10′ x 4′ deep, with very hot, steam-heated water. The American camp spokesman would not permit the men to immerse themselves during the summer months on account of skin disease. In the winter the tubs were used but not until the men had taken a preliminary bath before entering the tubs. The men were required to watch each other to see that none “passed out” because of the heat and their weakened condition. After bathing, the men would dress in all the clothing they had and go to bed for the night. Even then the prisoners would fill their canteens with hot water and place them beneath the covers. With these precautions, the men slept comfortably through the cold nights. Every two barracks had an outside wash rack, 16 cold water faucets and 16 wood tubs with drain boards. Prisoners washed their clothes by scrubbing with brushes on the drain board and rinsing them in the tubs. There was a constant shortage of soap.

OL: The mineworkers had to take a bath in the mining-compound with two large tanks with hot water, because you needed it to wash off the coal dust. I think it was the same in the sink factory.

mess hall. There was one unit mess with 11 cauldrons and 2 electric cooking ovens for baking bread, 2 kitchen ranges, 4 store rooms and 1 ice box. Cooking was done by 15 prisoners of war, 7 of whom were professional cooks, all working under the supervision of a Japanese mess sergeant. The men working in the coal mines were given 3 buns every second day to take with them for their lunch when they did not return to the camp to eat. Other days they were given an American mess-kit level with rice. Prisoners ate in the mess hall in which were placed tables and benches.

Goldy: The mess was entirely ruled by Lieutenant Little. If supervised by a Japanese mess sergeant, it was seldom evident. Little went as far as ingeniously constructing scales to make sure the POWs did not get an extra grain of rice. People working in the mine received only two meals a day. Going to work, they received a box about the size of a 25-cigar box with steamed rice and topped off by several slices of salted radishes and several strips of soy-soaked seaweed.

OL: There was plenty of hot tea in a huge wooden container in the mess hall, but it was tea from the stems only; tea leaves were not for POWs.

(e) food. Usually consisted of steamed rice and vegetable soup made from anything that could be obtained, three times a day. Upon occasion of a visit to this camp by a representative of the Red Cross in April 1944, a splendid variety of fats, cereals, fish and vegetables were served, which naturally impressed the representative, and in his report to headquarters he called particular attention to the menu. It is known that the spread was to impress the Red Cross man, and that it was the only decent meal served in two years. Rice and soup made with radishes, mostly water, remained the diet throughout. The men working in the mines were given 700 grams of rice, camp workers 450 and officers 300. Our American camp doctors stated that such scant ration was insufficient to support life in a bed patient. All of the prisoners were skeletons, having lost in weight an average of around 60 pounds per man. Again, only men in the mines were given buns to eat. The city water was drinkable.

Goldy: I do not recall any vegetable soup or buns except on rare occasions. We were given a roll or baked sweet potato when we came out of the mine at the end of the work shift.

OL: I have never received any bun — this was luxury — as a meal for the mines, neither as one of the other meals, with the exception of 2 or 3 times we got baked bread (a third of a loaf as a complete meal). As for a meal, it normally was always rice with some pickled vegetables and/or seaweed and not more than a spoonful. I think the POW-personnel working as cooks did their utmost to make the best of it.

LD: Several POW’s have mentioned buns, however several noted that the buns were allotted by the mess hall crew and receiving one was sometimes dependent upon who, at the time, the mess crew “favored.”

(f) medical facilities. Medical section and surgical section of the infirmary had ten rooms each with capacity for 30 men. Isolation ward could accommodate 15 men. Daily medical and dental inspections by American officers, but they had but little to work with in the way of medicines and instruments. The dentists had no instruments and could only perform extract ions, and without anaesthesia. For dysentery, the Japanese provided a powder which they concocted, the use of which produced nausea and diarrohea when administered to the American patients. There were no American hospital corpsmen in this camp until April 1944, when 10 men were added to the hospital corps with two doctors and one dentist. After October 1944 medical supplies were provided and an operating room installed. Prior to October 1944 the camp was practically without medical supplies. The Japanese doctor was entirely disinterested.

OL: The only doctor I have seen during my 18 months was the Japanese doctor and American orderlies — mostly Navy personnel — who did an excellent job under these circumstances. I myself was treated because of ulcers because of lack of vitamins — two times by incision with a razorblade with no painkillers and another time because of a kind of tropical open wound, neglected and looked very bad and like green moss growing on it, but the orderly managed to clean the whole wound with pincers up to the fresh meat and powdered it with silver-nitrate of which he (the orderly) still had something left.

(g) supplies (1) Red Cross, YMCA, other: The first Red Cross and YMCA supplies were received early in 1944 on the Japanese ship Teia Maru. The items in the food parcels were doled out to the men sparingly provided he had a consistent work record in the coal mine and was not guilty of infractions of rules. In the aggregate each man was given the equivalent of about one complete parcel during the full period of the confinement. The favoritism shown the mine workers in the distribution of parcel items defeated the intention of the Red Cross because it tended to give protein foods to the more healthy rather than to the weak. The 1944 Red Cross shipment contained medicines, surgical instruments and other supplies which the Japanese refused to make available for the benefit of the invalid men, but helped themselves to them. The YMCA furnished several hundred books. (2) Japanese issue: The clothing (cotton) was issued by the coal mine company and was adequate. British overcoats were given out by the Japanese army. Each prisoner was given three heavy cotton blankets and a comforter made of tissue paper and scrap rags and scrap cotton. The canteen was practically bare. From it the men received regularly five cigarettes per day. Canned salmon could be bought about every two months, one can per man.

Goldy: I do not recall canned salmon, but I recall a round container containing dry fish powder, which we used as a condiment over our rice. At one time there was a beached whale, and we got left-overs.The whales was spoiled and some chose not to eat any. They were the fortunate men, as the whale made most of them very sick. The Red Cross parcel was a joke and not even worth mentioning.

OL: Rationing of cigarettes was based on one cigarette for one working-day; that is one pack of 10 cigarettes for one ten-days shift; I never have seen the mentioned can of salmon. Because of the scarceness of cigarettes they were priceless; two cigarettes for a half bowl of rice, or one and a half cigarette for the soup was a common daily deal in the mess hall. During my time I received one Red Cross parcel, that is to say that we only received the non-food articles; the cans of food were stored by the Japanese and occasionally we saw or tasted some in our soup and the market-value in cigarettes was accordingly double or triple! Unfortunately this storage-room (like my barrack) was also hit and burned down when our camp was hit during a bombardment.

(h) mail. (1) incoming: First incoming mail was received in March 1944, thereafter each 60 days. Some received mail, some received none at all. It as all at the “whim” of the Japanese. However, if there was bad news, the Japanese most always made sure a POW received that mail.

(2) outgoing: Prisoners were allowed to write a card about every six to eight weeks. Very few made them “home.”

(i) work. In coal mines and zinc smelters three shifts per day of approximately 100 men per shift. Conditions in the mines were pronounced dangerous although only three men were killed outright during the period of confinement of 22 months. Many men received painful injuries from falling rock and other causes. Fortunately for the prisoner there was among the group an experienced coal miner who gave the men safety talks and pointed out some of the dangers of coal mining, which were not apparent to the novice miners. The coal mines were operated largely by American prisoners, the smelters by the British and Australian prisoners. Coal mines were approximately 1 kilometer from camp. Hours of work: 12 hours per day, 30 minutes lunchtime. The men were given one day off every 10 days.

Goldy: My left hand was crushed in a mine cave-in and thanks to the expertise of Dr. Hewlett, it was able to be repaired when I returned to the US and entered a VA hospital.

OL: In the mine we were divided in working-shifts of about 15-20 men to work in one coal-galley supervised by a civilian hanchou who told you with arms and legs what you had to do and then find out for yourself. There were no instructors or something of the kind. The shifts were a 10-day shift and depending on the changing of the shifts you had a day (off) in between and that only occurred once in a month. Because of roll-calls and endless counting procedures in the Omuta Camp and on the mining compound you were about 12 hours ¨busy.¨ You had quite a rotten day when there also was one of the regular inspections on the camping ground. Work in the mines was done mostly by POW-s and also Korean contract-workers; unpleasant people.

(k) treatment. Often the men were beaten without cause with fists, clubs and sandals. Failure to salute or bow to the Japanese was an offense which usually was followed by compelling the prisoners to stand at attention in front of the guard house for hours at a time. Some men were beaten daily and other harassed by Omuta Camp guards while trying to sleep during their rest time.

OL: The worst cases I saw were an American NCO Johnsen or Jones (something like that) who got a beating in front of the guardhouse with a rod or something of the kind, because he wore his US Army cap. The beating (we saw it from our barrack) was so bad that he died the next day. In another case an Australian who took a nap in the coal mine and fell asleep, without warning his other companions; so at the roll call outside he was missing. After we were back in the camp again he had woken up and reported to the guards of the other shift. The Japs considered this as an effort to escape and was punished by kneeling in front of the guardhouse with a bamboo stick between his knees and calves on his legs during the whole night in wintertime. The result was quite evident: both legs to the knees amputated. But he survived anyway.

(l) pay. (1) Officers: were paid 20 yen per month until June 1944, when it was increased to 40 yen less 18 yen per month for mess. Each prisoner received 5 cigarettes per day regularly except for about one day per month. Postal savings accounts for officers were deposited with Protecting Power amounted to 7,688.26 yen. Prisoner of War headquarters ran its own destitute welfare. (2) Enlisted men: NCOs were paid 14 sen per day and privates 10 sen per day. No postal savings were deposited with Protecting Power.

OL: The payment was very unimportant to us as long as we received our cigarettes each 10 days a package of 10 and toothpowder and some soap.

The General Courts Martial of Lieutenant Commander Edward N. Little

November 13, 2018 By Ddancis, Posted In Navy, Marines, & Coast Guard, WWII Pacific

Today’s post is written by William Green, Archives Technician in Textual Processing at the National Archives in Washington, DC

U.S. Navy Lieutenant Commander Edward N. Little was a prisoner of war (POW) from April 1942 until August 1945, as one of the nearly 30,000 Americans interned by the Japanese during World War II. Having survived the Battle of Bataan and the Bataan Death March, Little arrived at the Fukuoka POW Camp 17 on August 10, 1943. Located 46 miles east of Nagasaki, Japan, Camp 17 was initially built by the Mitsui Mining Company, and most of the POWs were forced to work in the nearby Miike Coal Mine. As the highest ranking Navy officer, Little was assigned to be the Officer in Charge of the mess hall for Camp 17.

There were 1,737 POWs imprisoned at Omuta Mine Camp Fukuoka Camp 17, including 730 Americans, 420 Australians, 332 Dutchmen, 250 Brits, and five of other nationalities. One hundred thirty-eight POWs died while imprisoned, including thirty-seven Americans. Four Americans were executed or murdered by the Japanese. One man was executed for attempting to escape and another for fraternizing with Korean mine workers. Two others were killed for infractions at the mess hall: one for stealing buns and another for trading his rice for cigarettes. These two men were allegedly reported to the Japanese by Lieutenant Commander Little.

Little’s Courts Martial resulted after the War Crimes Office received numerous complaints about his conduct. Following the camp’s liberation in August 1945, dozens of former POWs reported violations of Rules of Land Warfare and Human Decency at Camp 17. One former POW, U.S. Army Corporal Billy Alvin Ayers, stated: “I wish to place some of the blame of such treatment of the men on LCDR Little, who collaborated with the Japanese authorities by reporting infractions of the rules to the Japanese authorities rather than dealing with them in their own way.” Another POW, William D. Lee, U.S. Army, attested that “the Japanese would slap someone’s face for a minor infraction but never deprived an offender of a meal. Little would often punish men by depriving food, many of which were also suffering from fever, diarrhea or beriberi.”

Following an investigation of the allegations, a General Courts Martial was convened on January 15, 1947, at the U.S. Naval Gun Factory in Washington, D.C. Lieutenant Commander Little was charged with the following crimes:

Charge 1: Conduct Unbecoming an Officer and a Gentleman.

Charge 2: Maltreatment of a Person Subject to his Orders.

Charge 3: Conduct to the Prejudice of Good Order and Discipline.

In addition to the three main charges, twenty-two additional specifications charged that Little:

1) Kept and consumed more than his share of food contents of Red Cross parcels, delivered to him for distribution to the POWs at Camp 17.

2) Beat U.S. Army Corporal Bertram Freedman corporal, by striking and throwing him to the floor, causing Freedman to fracture a rib.

3) Ordered the beating of U.S. Army Corporal Russell E. Beasley, resulting in multiple wounds and bruises.

4) Deprived meals to multiple POWs on numerous occasions, knowing that the daily ration furnished by the Japanese was grossly inadequate, thereby aggravating their undernourished conditions.

5) Discarded edible rice into the garbage or on the floor of his office as a form of punishment.

6) Reported his fellow POWs to the Japanese, knowing that the Japanese authorities at the camp caused infliction of unreasonable and cruel punishment upon American POWs who were reported to them. In particular, Little:

-

Reported U.S. Marine Corps Corporal James G. Pavlakos for selling a bowl of rice to James O. Wise for two packs of cigarettes. Pavlakos was punished and beaten for nearly 30 days by the Japanese until he died.

-

Reported U.S. Army Corporal Frank J. Savini for stealing one cup of flour from the mess hall, resulting in him being starved and beaten for eight days.

-

Reported U.S. Army private William N. Knight for stealing nine buns, resulting in him being starved and beaten for four days until he died.

-

Reported U.S. Navy Lt. Biagio H. Furnari for stealing one bun from the mess hall, resulting in him being stared and beaten for ten days.

Little denied all of the charges and specifications.

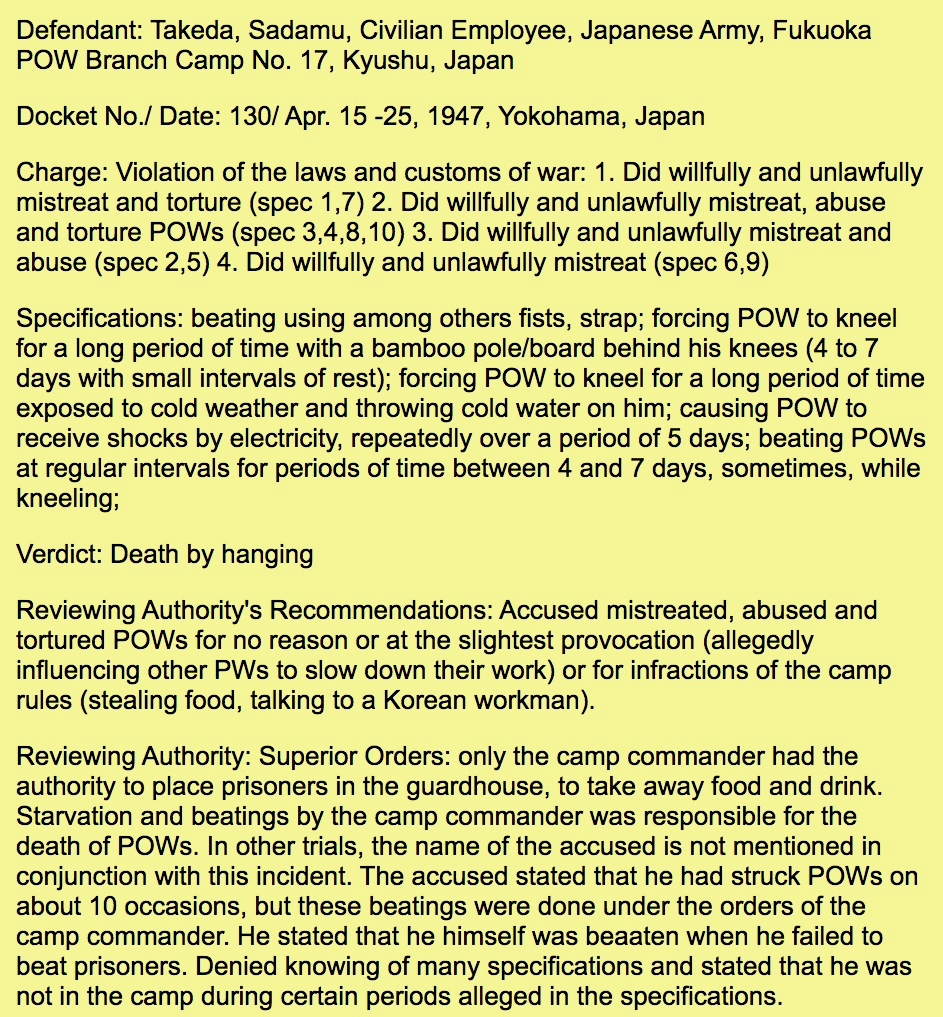

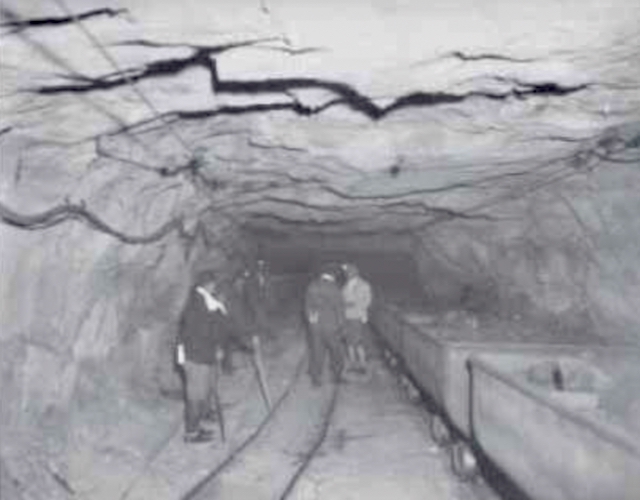

These photographs show the dangerous conditions for POWs working in the Omuta Mines – below Mikata Coal Mine taken Dec 1945

Above: All the support timber has been taken for general production anywhere across Japan leaving the mines vulnerable and dangerous.

Above: Mikata Coal Mine, Omuta – shows dangerous timber supports deteriorated because much of the timber has been removed. Imagine how terrifying it was for POWs to work every day/night in these conditions.

WHO WAS LT. COMMANDER LITTLE?

Little, age 39, had served in the U.S. Navy since 1924. He entered the service as an enlisted man and served for two years before being admitted to the Naval Academy in 1926. Due to that background, he believed he understood both the viewpoint of enlisted men as well as the officer’s leadership obligations to his men. Little, as one of the first 500 Americans to first arrive in Camp 17 from the Philippines, felt that it was his duty to get as many of the original 500 men home as possible. He testified that he believed the best way to do that was to maintain a fair and strict mess hall.

Violators of his rules in the mess hall at Omuta POW Camp often received punishment. Violations included trading food, skipping the line, stealing, and not sterilizing utensils. Punishment for infractions usually meant losing one’s daily ration. Private James Stacy, U.S. Army, testified that “Little often took away a man’s ration for some fancied wrong” and “took great delight in giving his orders in Japanese.” Little frequently gave orders to American POWs in Japanese, even when the Japanese authorities were not present.

Little said he didn’t know why he did it, only that it became a habit.

The most deliberated specification concerned the death of private William Knight, who was suspected of stealing nine buns from the mess hall. Knight had a reputation for theft in the camp and, according to Little, was “a habitual offender.” Knight even wore insignia on his jacket to signify that he was a known thief. Japanese guards took Knight to the camp prison and beat him with a pole that was two and a half feet long and six inches in diameter. When he lost consciousness, the Japanese revived Knight with cold water then continued beating him. Knight suffered fractures of his arms, legs, and skull, and died after four days of beatings.

Eighteen POWs testified that Little announced:

“I am the one who turned Knight into the Japanese this morning and I hope they beat him to death.”

The message was unmistakable: If you stole from the mess hall, Lieutenant Commander Little would tell the Japanese.

During the trial, Little claimed that he was shocked to learn of Knight’s death and denied reporting Knight for anything, at any time. Little also testified that he had tried to forget as much as he could from that time and didn’t remember many of the things he was accused of saying and doing.

The Japanese commander in charge of the camp was Captain Isao Fukuhara. During his own hearing in February of 1946, Fukuhara testified at the Tokyo War Crimes Trials that Little had requested punishment of a fellow prisoner (Knight) for stealing bread. Captain Fukuhara was later sentenced to death.

Little’s overall defense for his conduct relied on Article 8 of the Articles for the Government of the United States Navy.

Article 8 states that punishment, such as a General Courts Martial, may be inflicted on any person in the Navy who refuses or fails to use his utmost exertions to detect, apprehend, and bring to punishment all offenders, or to aid all persons appointed for that purpose.

Little’s defense claimed that because he was subject to the Articles for the Government of the Navy, he was under an obligation to report offenders. Essentially, his argument justified his right to report offenders to the Japanese authorities while denying ever doing so.

On June 17, 1947, after five months of trial, Little was found not guilty on all charges and specifications.

Following the trial, Little continued to serve in the U.S. Navy, including during the Korean War, and later retired with the rank of Commander. Edward Little died on June 28, 1967, at age 59, and was buried with honors at the Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno California.

What is most surprising is that former Omuta POWs did not attempt to take his life or at least make serious threats!

Source:

The records for this post are from File #157,962, Records of the Proceedings of General Courts-Martial, 1942 – 1951 (NAID: 2143324), RG 125: Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Navy).