Major Bruce Hunt A.A.M.C. served in WW1, studied medicine on return to Australia. He was a tall, well built man with a personality to match.

Major Hunt left Changi with ‘F’ Force, travelled by train to Bampong in Thailand.

Hunt with his medical team marched with ‘F’ Force on the 300 kilometre march from Bampong to Shimo Sonkuri, Burma. They marched at the rear to ensure stragglers were assisted to the next transition camp. Hunt also ensured POWs were taken care of and did not hesitate to stand between the Japanese guards and their well-being. Many of ‘F’ Force were unwell before leaving Changi and not fit for a working party. It was a tortuous journey.

The POWs soon learnt of or experienced the dedication of Hunt and Hunt quickly earned the admiration of the marching POWs and of those at camps which ‘F’ Force passed through on their journey north.

Although several dedicated and committed M.O.s assisted Major Bruce Hunt, he was the most respected by the men of F Force. He outshone other senior service officers and was an excellent Camp Commander. The Japs also respected Bruce Hunt. Hunt’s services and commitment to Australian and British POWs was nothing short of remarkable.

Much of the following is taken from the report by Bruce Hunt. Major A.A.M.C., Commanding Officer, Burma Hospital.

On 29 June 1943 IJA first intimated their intention to construct a hospital in Burma to receive ‘F’ Force men incapable of work for at least two months. Rolls were prepared for 2,000 men. On 8 July plans were cancelled. On 21 July fresh orders were issued to prepare rolls for a 1250 bed hospital. Lt.Col Harris, commanding ‘F’ Force appointed Bruce Hunt O.C, Hospital on 1 July and Hunt was taken to Burma by the IJA in company with Lieut. Saito to examine the hospital site.

Bruce Hunt returned on 2 July and left on 30th July with the advance party for Burma.

Later when evacuation of sick to Tanbaya took place, several camps were closed down and POWs were concentrated at 2 main camps at Kami Sonkurai and Sonkurai with the new HQ Camp being established at Nikhe.

When Changaraya, Nikhe and Shimo Nikhe were about to close an order came through on 2nd August to regroup at Sonkurai and Kami Sonkurai so each camp could supply the same number of POWs for the Japanese engineers on the line.

Patients too ill to be transferred to the newly established Tanbaya Hospital Camp and expected to die were ordered to remain with their carers until told otherwise.

Four diseases dominated Tanbaya Hospital Camp. In the order of mortality, they were Dysentery, Tropical Ulcers, Beri Beri and Malaria.

Major Hunt, as O.C. of the Hospital was responsible for all medical treatment and administrative control of all medical personnel whether professional or amateur and of all patients. Lt. Col. Hutchinson as Administrative Commandant of the camp was responsible for such services as cooking, securing of wood and water, hygiene and pay. Tanbaya ran smoothly and efficiently as was possible under the circumstances.

Patients were segregated as far as was possible to assist in facilitating treatment and prevent cross infection.

There were seven wards and each held about 190 men under the control of a Wardmaster who was a combatant officer who had several assistants. The Wardmaster was responsible for nominal rolls, discipline, hut cleanliness, messing, canteen supplies and generally everything taking place in the ward except those matters which involved technical medical knowledge or skill. Additionally the Wardmaster through the medical officer or senior nursing N.C.O. had supervisory control over activities of the nursing orderlies in regard to their non-technical functions.

This system with the wardmaster was first devised in Shimo Sonkurai Camp and was further used in camps in Burma. The system was found to be of the greatest possible assistance in running hospitals. Discipline and general ward efficiency were better than they usual under N.C.O. control

Bruce Hunt wrote “I was particularly fortunate in having a very able body of Wardmasters; they worked, ate and slept in their wards and were completely devoted to their duties and to the interests of their patients. I should like here to express my appreciation of their valuable services”.

Hunt referred to the seven wardmasters including Captain George W. Gwyne, WX3450 from 2/4th who was also with ‘F’ Force. Other wardmasters were Lt. I. Perry (2/1 Heavy Bty A.I.F.), Capt. H. Walker (2/26 Bn A.I.F.). Major R. Hodgkinson (R.A.S.C.), Major W. Auld ( M.A.O.C.), Capt. B. Berry (2/10 Fd. Rgt. A.I.F.) and Lt. Col. Ferguson (18 Div H.Q.)

A Wardmasters’ conference, attended also by O.C. hospital, Registrar and Messing Officer, was held at 1530 daily, and this proved a most satisfactory means of keeping the wards in close touch with camp policy.

A daily check took place at 1500 hours where all drug requisitions were checked and counter signed by O.C. – thus providing a fair distribution to wards and to assist in conservation of supplies.

As the health of patients improved and they became fit for camp duties they were sent to the ”‘labour exchange” to be vetted by the O.C. Hospital and then assigned to various sections of the hospital to assist.

The R.A.M.C. and A. A. M. C. staff numbered 142 at the most – many of these men arrived as patients, died at Tanbaya or remained as patients throughout their time in Burma. Nine members of R.A.M.C. and eight members of A. A. M. C died at Tanbaya. Five R.A.M.C. members and nine from A.A.M.C. remained behind as seriously ill patients when the bulk of Tanbaya Camp was moved in November 1943.

The maximum number of medical corps personnel available for work at any one time was 62 however was generally between 40 and 50.

With such low numbers it was necessary for volunteers from non-medical units to attend to the ongoing and constant needs of patients. The devotion and tireless effort of these volunteers is not only praised by the medical teams but the patients. They gave their time throughout the night and day.

Some volunteers were as good as and sometimes better than the professionals.

Many patients were in such advanced state of illness on arrival at Tanbaya, in particular the patients from Sonkurai No. 2 Camp where it was believed all very sick patients were evacuated. This wasn’t the case with other Camps who did not transfer their most sick men.

DYSENTERY

The dysentery wards were the most depressing. The patients fought bravely forcing down rice day after day and week after weeks hoping for medical supplies to arrive.

There were 114 deaths from dysentery and a total of 334 deaths with dysentery playing a part with other illness(es). An attack or recurrence of dysentery often brought on sudden death for patients suffering from beri beri or ulcers.

Tanbaya received the first and only supply of Etemine sufficient for 5 patients in November.

BERI BERI AT TANBAYA 1943

68 patients died of beri beri and a further 260 cases died with beri beri as one of the causes of death.

Beri beri was widespread throughout the camp and at its worst there were more 600 patients showing clinical manifestations. The disease seemed more severe at Tanbaya with oedematous and cardiac types predominant. Cardiac berri beri was common and severe. It was not uncommon for a sudden death to occur in the middle of the night.

TROPICAL ULCERS

Ninety-two patients died of ulcers alone at Tanbaya and 105 of ulcers complicated by other diseases. 60 amputations were performed. Because of the very poor general health of a patient undergoing an amputation many died of complications.

The lower extremities of the body were more prone to ulcers, in particular the region of the tibia. However ulcers could and did occur in any area of the body – lower spine, groin, elbows, wrists and fingers. An ulcer could follow a small scratch or small cut. Huge areas of skin and flesh were eaten away. In some cases bone was eaten away.

In the absence of Sulphanilamide and lodoform the only options included cleansing with Eusol or Saline 2-3 times days with often disappointing results.

MALARIA AT TANBAYA

As was the case in all railway camps malaria was universal throughout Tanbaya. During August and September malaria was recurrent and was the worst owing to a shortage of quinine supplies. At that time, 7 days was the maximum treatment period. After September when supplies were more readily available the time for treatment was 24 grams daily for 7 days and 32 grams daily for 12 days accompanied by .02 Plasmoquin daily.

One of the concerning features of malaria at Tanbaya was the high degree of resistance to quinine with some cases taking as long as 6,7, or 8 days for the fever to come under control.

Beginning in September 1934 strong representations were made to IJA that hundreds of patients would not survive a long railway journey south. As a result leniency was allowed in selection of patients chosen to travel. The careful choice of 900 patients who left Tanbaya for Kanchanaburi resulted in only 2 deaths from the arduous 5-6 day journey.

218 patients remained behind at Tanbaya with approximately 85 suffering from dysentery, 65 from ulcers and majority of the remainder had beri beri.

102 staff remained behind to look after them.

No drugs were delivered by IJA until 5th November. The pitifully small supply was totally inadequate.

The survivors from Tambaya left in March and spent around one month in Kanchanaburi where they met up again with Major Hunt. They were taken by train to Singapore some time in April, 1944, arriving approximately one year after their departure.

Bruce Hunt wrote in his report at Kanchanaburi 23 December 1943 in which he acknowledged the dedication of the following medical staff Major W. J. E. Phillips (R.A.M.C.), Capt. Emery (R. A. m. C.), Capt. F. J. Cahill (A. A. M. C.), and Assistant Surgeon Wolfe (I. M. D.). Outstanding nursing work was performed by Sgt. G. Nichol (A. A. M. C.). and by Cpl. Skippen and Cpl. Sutton (R. A. M. C.).

The following has been taken from “The Albert Coates Story” by Albert Coates & Newman Rosenthal”

“Towards the end of 1943, the Japanese brought a number (nearly two thousand) of the worst cases of tropical ulcers, gangrene of the legs and avitaminosis from the Thailand side of the railway to a camp at the 50 Kilo mark.

Major Bruce Hunt of Perth, WA was in charge of the party and on his way passed through 55 Kilo. camp, where he was detained by the Japanese guards. I was informed of his presence in the guardhouse and was able to talk for a while with my old friend of student days who had been an honoured staff member of the 13th AGH.

Some time later I was instructed by the Japanese to proceed to 50 Kilo camp and inspect the sick there.”

“Captain Frank Cahill, a younger surgeon who had been with me in the 10th AGH and had visited our 55 Kilo camp was in charge of the leg ulcer patients. They were in a shocking condition and mortality was very high. Most of them were already past help by amputation. Of the 1924 patients, 660 died. The conditions in that camp were even worse than those in the 55 Kilo. Camp. There were no facilities for operations. The camp was the usual abandoned working camp now called a ‘hospital’. It was nothing but a dirty depot for depositing the dying. Hunt and his colleagues had put up a gallant fight against hopeless odds”.

Please read about Tanbaya Hospital Camp

Bruce Hunt was repatriated in 1945 he was awarded MBE in 1947 and testified before war crimes tribunals.

He was a devoted physician, beaten several times by his Japanese captors for standing up for his men.

Bruce Atlee Hunt died 29th October 1964 at Applecross, Western Australia

Men of 2/4th who died at Tanbaya Hospital camp included:

WX9131 Goodwin, Reuben ‘F’ Force d. 6 Nov 1943 beri beri and dysentery, 27 years (former Fairbridge student)

Born 1916 England he was sent to Fairbridge Farm School, Pinjarra. Goodwin had been working at Konnonggorring, WA’s wheatbelt area for several years before enlisting 30 Oct 1940. He later joined 2/4th’s ‘B’ Coy.

He left Singapore mid April 1943 with ‘F’ Force Thailand by rail for Burma-Thai Railway

Please read further about ” Force Thailand

WX7801 Hackshaw, Albert ‘F’ Force d. 2 Nov 1943 tropical ulcers aged 43 years just two days prior to Goodwin. Together their funeral was conducted by British Army Chaplain Duckworth on 15 November 1943 although Hackshaw was buried on 2 November.

Hackshaw born England 1900 came to Australia with his parents and large family of siblings. His younger brother enlisted the same day as Albert. Reginald Hackshaw WX7800 died in New Guinea.

Prior to enlisting August 1940, Hackshaw had been working at Roebourne, employed as a foreman to Main Roads Department.

WX9320 Heal, Herbert William

‘F’ Force d. 22 Dec 1943 beri beri and dysentery aged 33 years.

Like many young men, Bertie had never married or possibly held a permanent job because of the depression. He had moved to Toodyay working as a yardman prior to enlisting.

After the war his body as well as those of all who perished at Tanbaya, were moved to Thanbyuzyat War Cemetery, then Burma (now Myanmar).

WX9849 McIntosh, Archibald James L. (Archie) ‘F’ Force d. 10 Nov 1943 beri beri and dysentery aged 23 years.

Archie’s funeral was included Goodwin and Hackshaw on 15 November held by Chaplain Duckwith.

Archie was one of a number of 2/4th boys from Bassendean.

Please read further details of Archie McIntosh

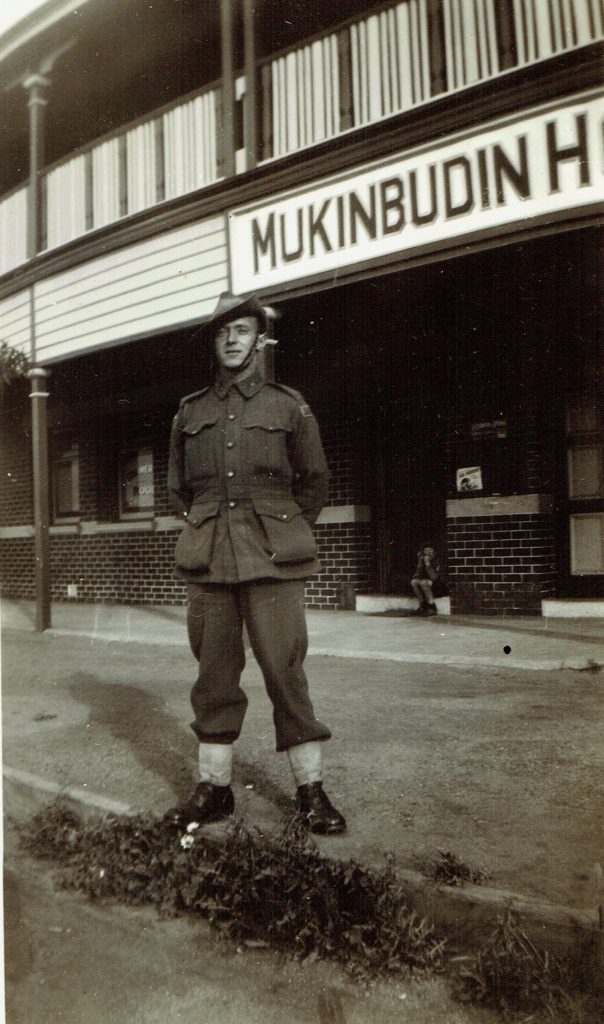

WX9143 SMITH, Montaque Joseph of Mukinbudin died 13 November 1943 of dysentery and tropical ulcers aged 27 years.

WX8699 Thackrah, Cyril Bernard

‘F’ Force d. 19 September 1943 of dysentery and malaria. He was 40 years old.

Known as Barney, Thackrah came to WA as a young man with his brother. Barney’s brother Dudley died at Katanning.

Barney’s older brother was KIA Flanders, WW1.

Barney was one of the earliest deaths of 2/4th men sent to Tanbaya.