Timeline

World War II Declaration – Sept 1 1939

On September 1st, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Seventy-two hours later Neville Chamberlain informed the British People that their country was at war with Nazi Germany. Robert Menzies, Prime Minister of Australia, took the onus upon himself of supporting the ‘Mother Country” by declaring that as Britain was at war with Germany so too was Australia.

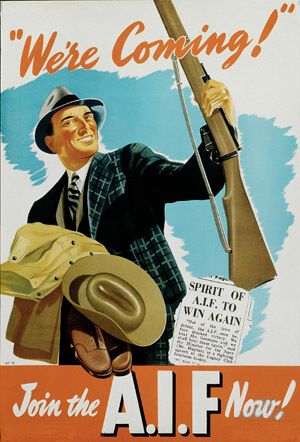

As had occurred at the commencement of World War 1, many Australian youths headed for recruiting offices and enlisted for overseas service. There were many reasons why these men volunteered to serve in a war which was once again to be fought half a world away on the fields of Europe. Some were unemployed and saw it as a job; some wanted to see the world and this was an opportunity to do so at the government’s expense; some volunteered out of a spirit of adventure; some because they saw, even at that stage, the horrors of Nazism; and some out of loyalty to the ‘Mother Country’.

2/4th Machine Gun Battalion Formed

On 7th November 1940 it was announced by the Minister for the Army, Francis Fordes, that Lt-Col M.J.Anketell, was to form and train the 2/4th Australian Machine Gun Battalion.

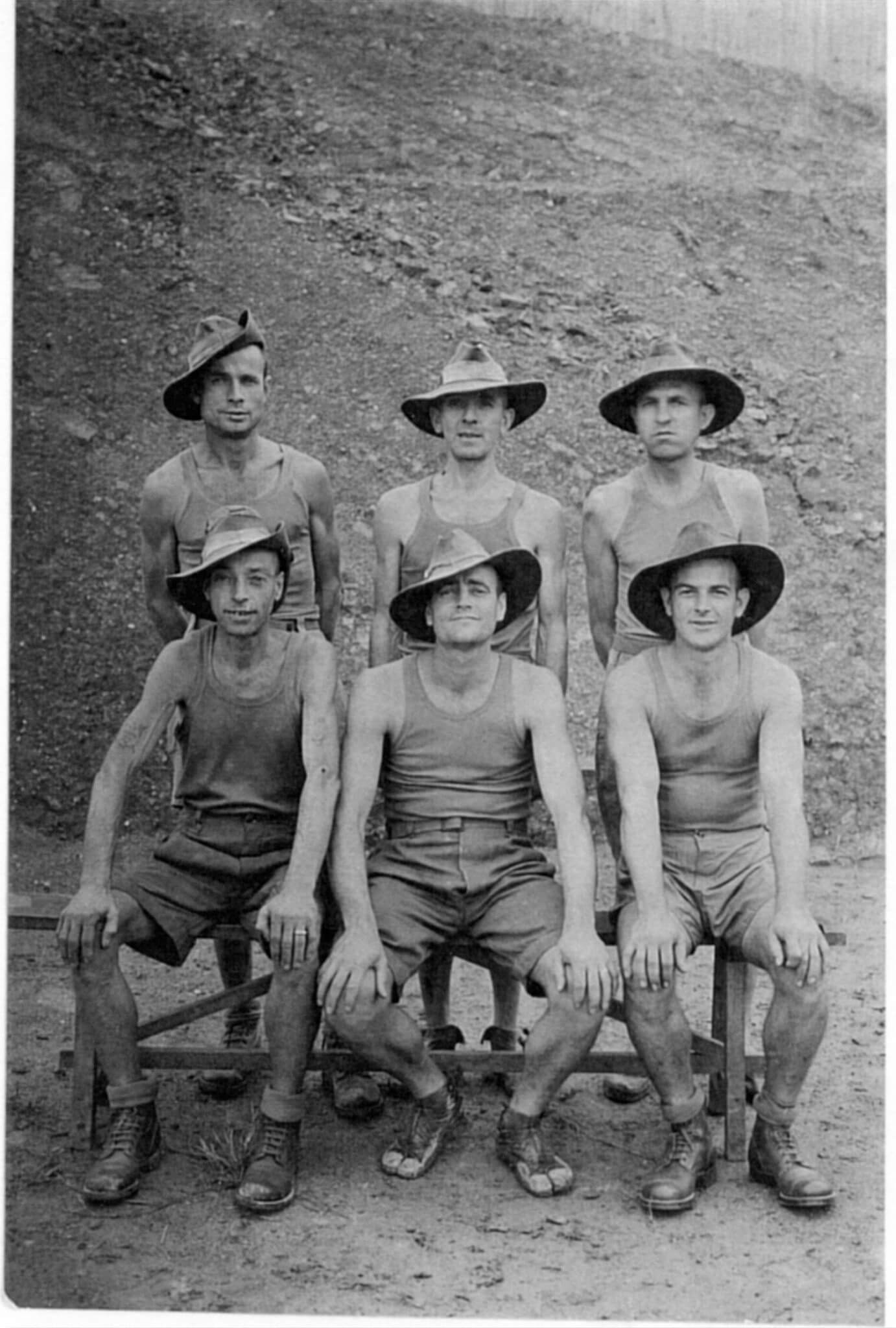

Western Australia’s 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion was raised as one of the support units for the ill-fated 8th Division. Formed with men from across the state, they all came together at Northam military camp, east of Perth, where they carried out their initial training.

March from Northam to Perth

Film courtesy of Luke Tannock, great nephew of WX9413 Frank Noble.

Battalion embarked Duntroon or Katoomba to Adelaide

In July 1941 the bulk of the battalion boarded the coastal steamer Duntroon at Fremantle. We were bound for Woodside, a training camp in the Mount Lofty Range 30 miles East of Adelaide. Harris p11

Move to Darwin

After three months in South Australia we left Woodside for Darwin, travelling by train, changing at Quorn to the 3ft 6inch gauge to make Alice Springs, where we spent the night. The most popular recreational activity there was watching an open-air picture show from the depths of a deck chair. The next day we set off along the Stuart Highway in a convoy of trucks bound for the rail terminal at Birdum, camping each night at regular staging post. When we reached the desolate siding which was then the Northern territory’s southern rail terminal, we found a string of old cattle wagons waiting to take us the rest of the way to Darwin,. There simply weren’t enough passenger coaches to accommodate the military needs of a nation at war.

The cattle trucks were covered by tarpaulin. The ancient locomotive known as the Darwin horror, was powered by steam from a wood burning boiler. At regular intervals it would shower the whole train with sparks and soot. Our destination, Winnellie, a half finished camp straddling the highway a few kilometres south of Darwin was quite unlike Woodside.

Japan attacks Pearl Harbour

December 7th 1941 was another crisis, but of world-shattering proportions, Japan attacked Pearl Harbour. The USA entered the war, and now there was a ‘new’ ball game.

Battalion departs Darwin

Told of their move just before Christmas, the battalion left Darwin on 30 December, embarking on the ‘Westralia’ or the ‘Marella’ to Port Moresby where they transshipped to the Cunard Liner ‘Aquitania’. The ‘Aquitania’ , only half full, sailed south to Sydney to take on more soldiers before sailing on to Fremantle to take on a small detachment, among them the reinforcements for the 2/4th, ‘E’ Company.

Battalion arrives Fremantle

On that early Thursday morning, January 15th 1942 (exactly one month before Singapore surrendered) as the ‘Aquitania’ sailed serenely into Gage Roads between Rottnest Island and the coast some of the men could see their homes.

The “Aquitania’ was to refuel, take on stores, water, equipment and a small detachment of troops, among them the reinforcements for the 2/4th, ‘E’ Company, and she was to be at anchor for about 36 hours.

The military authorities made a gross error. Because there had been problems in Sydney, and, because of the purported security risks, their decision was that the men would not be permitted ashore in Perth.

No shore leave? To men who could see their homes, or nearly so, and who had not seen loved ones for nearly seven months, and might never see them again, this was too much, especially when they learned that members of the ship’s crew had leave. With faultless logic the men reasoned; if the crew were permitted ashore, then security could hardly be a factor. As tankers, ferries and lighters came out to deliver, fuel, reinforcements, and provisions, so they carried back to port privates, corporals, sergeants, who had scrambled through portholes, slid down ropes, commandeered a gang plank, disobeyed orders (told one subaltern, silly enough to draw a pistol and threaten the ‘deserters’ ‘piss off and grow up’) and so made their triumphant home-coming. Saggers p7

Ninety-four men missed the departure of the ‘Aquitania’ for Singapore and were later sent north to Java, where they were subsequently captured.

2/4th arrive Singapore

Prior to the arrival of the 2/4th, it was the Japanese routine to bomb Singapore at precisely 11 o’clock every morning. By sheer luck on Saturday, January 25th 1942, the day the 2/4th landed, the Japanese bombers did not come. Saggers p8.

By this time the Japanese had captured Malaya and were preparing to attack Singapore. Similarly, the British were desperately preparing their defences and the battalion’s companies were sent where they were needed: B Company was sent to the British Manchester Fusiliers, constructing weapons pits around the Naval Base; C Company went to support the 44th Indian Brigade on the west and south-west coast of the island; D Company supported the 22nd Brigade on the north-west coast; and A Company was in the 8th Division’s reserve, close to the island centre.

After days of air raids, the Japanese attacked Singapore on 8 February – crossing the Johore Strait and attacking along the 22nd Brigade’s front and the 27th Brigade near the Causeway. Deployed to different units, the 2/4th’s companies were quickly in action but by 10 February the Japanese had captured the island’s west coast. Five days later the British forces were pushed back to a defensive line protecting the city. However, the battle was virtually over and on 15 February Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival surrendered Singapore.

The machine-gunners suffered heavily. Between 8 and 15 February the 2/4th had 137 men killed or missing, 106 men wounded, and 24 described as having “shell shock”. These casualties constituted almost one-third of the battalion. Worse was to follow, with the battalion held in Japanese prisoner of war camps for the next three years.

Following the surrender, the 2/4th was concentrated in Changi gaol. From Changi the Japanese took drafts of men to work throughout their Greater South East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere. Some of the battalion were sent to Borneo, while others worked on the Burma-Thai Railway or in Japan. By the war’s end, another 263 men from the battalion had died as prisoners. AWM

On 17th February 1942 the 14,972 men of the 8th Division that were able to walk, were marched the 17 miles to Selarang Barracks Changi. Ewen p560

Selarang Square Incident

On August 30th 1942 all Prisoners of war were urged by the Japanese to sign a pledge not to escape. Upon their refusal under the terms of the Geneva Convention, all British and Australian prisoners were congregated into the barracks square at Selarang Barracks until such time as they agreed to sign. Ewen p561

They were kept there for three days without food, although water (from 2 taps) was allowed for drinking. With over 15 000 troops squeezed into an area of approximately six hectares sanitary conditions were dangerously septic. With the very great risk of losing not hundreds but thousands to disease, the allied commanders instructed the men to sign, but as it was under duress, they were not bound to honour it. Saggers p64

Burma - Thailand Railway

Between November 1942 and October 1943 a force of about 60 000 prisoners of the Imperial Japanese army, together with an even greater number of locally conscripted labourers, was mobilized to construct a railway from Kanchanaburi in Thailand to Thanbuyzayat in Burma. Many died in the construction process including 12 000 POW’s (2800 of them Australian). They died from overwork, beatings and ill treatment, exhaustion, malnutrition and disease. McCormack & Nelson p1

There were several reasons behind the Japanese wanting to build a rail link between Non Pladuk, the 000.00 kilometre point in Thailand , and Thanbyuzayat in Burma, the 414.92 kilometer point. At the top of the list was the Japanese military’s involvement in the China-Burma Theatre. Tokyo approved construction to commence on 20th June 1942. Ewen p601

Concentration of Prisoners of War in Thailand 1944

Singapore to Japan

Early in 1944 ‘fit’ men were chosen to be sent to Japan from Thailand, Java and Singapore to work in coalmines, factories and shipyards. John Gilmour describes his departure from Singapore to Moji, Japan.

‘Many prisoners left Changi in large groups, designated ‘A’ Force, ‘B’ Force, etc, I was in ‘J’ Force. We left Selarang Barracks, Changi, for Japan on May 15, some 600 British and 300 Australians of the 8th Division, Australian Imperial Forces. The following day I was aboard the Weills Maru, a rusty old tramp cargo ship of some 5000 tonnes, built some 50 years earlier and taken off the scrap heap for war duties. She was old and slow. We were given two meals a day on the ship; rice and cabbage soup.

The worst and most dangerous period in a prisoner’s life was travelling in captivity. Over-crowding, sickness, disease and the dangers posed by Allied submarines caused much stress and anxiety. Conditions on board these ships were severe: over a 1,000 prisoners might be crammed into spaces suitable for a few hundred and given little food, fresh water, or adequate sanitation facilities. Some journeys lasted just a few days, but the longest was a voyage from Singapore to Japan which took 70 days (this was the Rashin Maru, known to prisoners as the “Byoke Maru”, or sick ship). The prisoners of war called these transports “hellships”.

The Rakuyō Maru (with 1,318 Australian and British prisoners of war aboard) and Kachidoki Maru (900 British prisoners of war) were part of a convoy carrying mostly raw materials that left Singapore for Japan on 6 September 1944. The prisoners were all survivors of the Burma-Thailand Railway who had only recently returned to Singapore.

On the morning of 12 September 1944 the convoy was attacked by American submarines in the South China Sea. Rakuyō Maru was sunk by USS Sealion II and Kachidoki Maru by USS Pampanito. Prisoners able to evacuate the ships spent the following days in life rafts or clinging to wreckage in open water. About 150 Australian and British survivors were rescued by American submarines. A further 500 were picked up by Japanese destroyers and continued the journey to Japan. Those not rescued perished at sea. A total of 1,559 Australian and British prisoners of war were killed in the incident, all missing at sea (1,159 from Rakuyō Maru, 400 from Kachidoki Maru). The total number of Australians killed was 543 (503 AIF, 33 RAN, 7 RAAF) including 36 members of 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion.

POW of Japan

Once in Japan Australian POWs were broken into small groups and scattered across many camps. These included Akanobe, Ikuno, Kobe, Naoetsu, Oeyama, Ohama, Osaka, Sakata, Taisho, Takefu, Tokyo and Yokohama, all on Honshu island; Zentsuji, on Shikoku island; Moji, Fukuoka, Hakarta, Omuta and Kanoya, on Kyushu island; and Nisi Asi-Betu, on Hokkaido island.

The POW workforce was used in a range of Japanese industries. Mostly they worked in coal and copper mines, iron and smelting works, and shipyards (welding, riveting and painting and as riggers).

Wherever they were, prisoners endured long working hours, infestations of lice and fleas, and bad health resulting from a poor diet. The Japanese winters were particularly severe and some prisoners died of pneumonia. However, some of the deprivations they suffered were also being experienced by the wider Japanese population as the US blockade strangled the Japanese economy in the later years of the war.

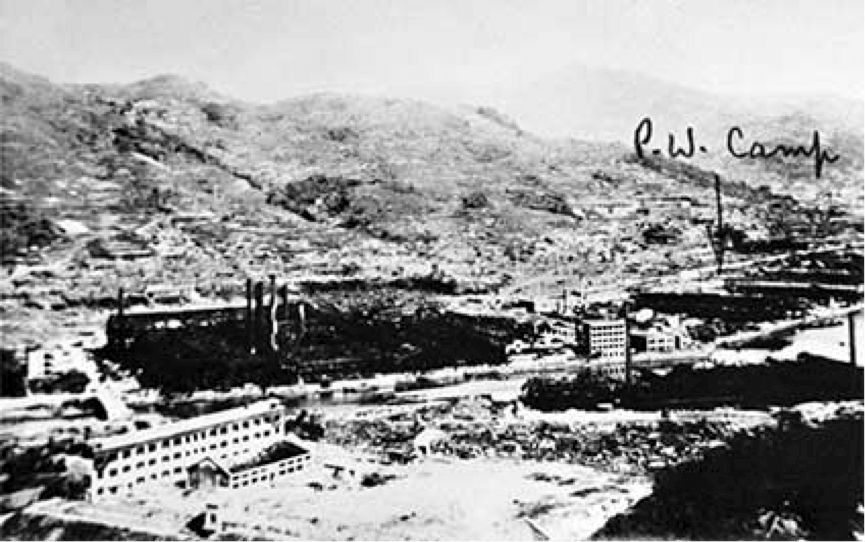

Prisoner of war (POW) camp 14, Nagasaki, after the date of the atomic bomb blast on 9 August 1945.

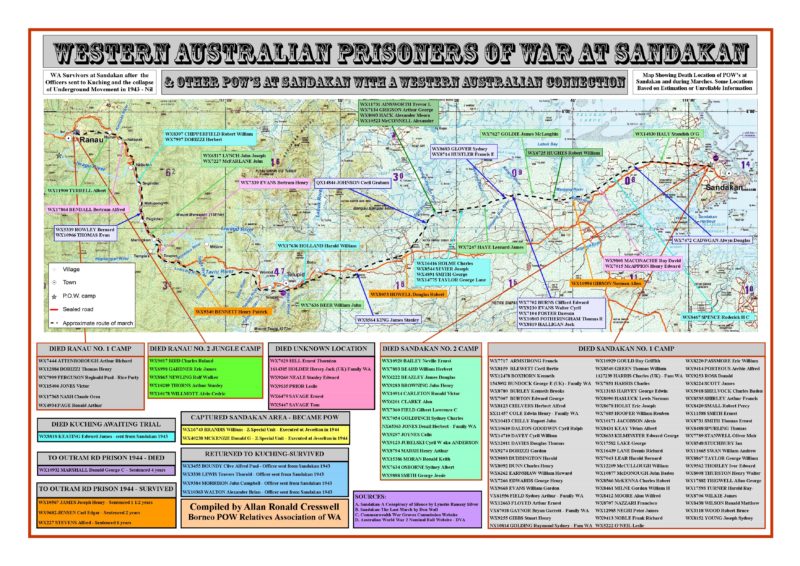

Sandakan

The Prisoners of War on ’B” and ‘E’ Force who were transported to the picturesque town of Sandakan in British North Borneo were involved in the greatest tragedy to befall Australian servicemen during WWII. The 2/4th’s contribution to these forces was thirty-three and thirty-six men respectively. Of these sixty-nine men the only survivors were Lt. John Morrison and Sgt. Alf Stevens from ‘B’ Force and Lt. Brian Walton from ’E’ Force. Ewen p675

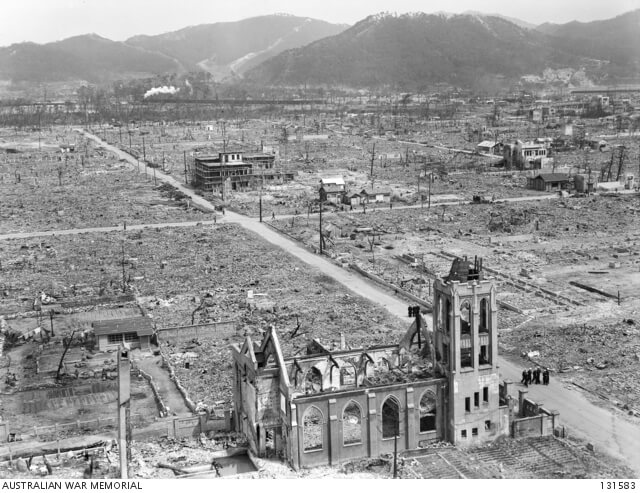

Victory in the Pacific

August 1945, devastated by allied bombing and the threat of invasion, Japan surrendered. On 6 and 9 August, American bombers had dropped atomic bombs on two Japanese cities, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively. The Japanese ceased fighting a week later on 15 August 1945 and on 2 September 1945 formally surrendered to the Allies in a ceremony on the deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. Other surrenders of Japanese armies in the field took place across Asia and the Pacific.

VP (Victory in the Pacific) Day, also referred to as VJ (Victory over Japan) Day, is celebrated on 15 August. This date commemorates Japan’s acceptance of the Allied demand for unconditional surrender 14 August 1945. For Australians, it meant that the Second World War was finally over.

The following day, 15 August, is usually referred to as VP Day. In August 1945 Australian governments gazetted a public holiday as VP Day and most newspapers reported it as such. However, the governments of Britain, the United States and New Zealand preferred VJ Day. It is not true, as some have claimed, that the day was originally called VJ and that the name was surreptitiously changed later.

Recovery of Soldiers to Australia

On the capitulation of the Japanese on August 15 1945, recovery teams from Australia moved into the South East Asia areas and repatriation was completed by the end of October. Of the 961 members of the battalion who went overseas, 137 were killed in action: and 263 died as prisoners of war in the hands of the Japanese. Harris p181

Altogether 14000 Australian prisoners of war of the Japanese came home. The men in Japan were gathered in by the Americans and came through Okinawa and Manila where they made their first contact with the Australian military. Many completed the journey South on aircraft carriers, the fittest played hockey on the decks, shooting sharks with 303’s, and all watching movies; ‘Casablanca’, ‘ Shine on Harvest Moon’, and ‘Heaven Can Wait’. In South East Asia most prisoners were flown to Changi and then waited to be called to a ship. Priority was given to the sick who were carried on board especially fitted aircraft or hospital ships.

Some of the prisoners had been away from their families for five years. Nearly all had been away for four years. Nelson p207