Dr C.R.B. ‘Rowley’ Richard, was appointed Regimental Medical Officer of the 2/15 Field Regiment (2/15 Field Regiment) in 1940.

Dr Rowley Richards was one of 42 Australian Doctor POWs on the Burma-Thai Railway, selected with ‘A’ Force, made up of 3,000 POWs including many 2/4th men under the command of Green. They sailed on three ships from Singapore mid May 1942 to south west coast of Burma. ‘A’ Force spent several months at Victoria Point, Tavoy and Ye repairing and enlarging aerodromes left damaged during the retreating British Forces. By 1st October Green Force commenced work on the northern Burma end of the railway, the first Australians to do so.

Richards was a young man, known as ‘Baby’. He never failed to remind the commanding

officers and men of the principles and adherence of hygiene, prevention of illness and first aid. He believed this to be the reason that no man under his care ever lost a limb.

This is one of Richards’ books, ‘The Survival Factor’ . He was the Force Doctor for Williams No.1 Mobile Force which came into being at 26 kilo camp, KunKnitway working through to the joining of the two rail ends in October 1943. They worked right through the wet season laying sleepers and rails as well as ballasting – hard and demanding work which took its toll on the POWs.

After the war Richards was one of those Doctors who was never interested in self-promotion. He focused his efforts on preserving and honouring the veteran’s memories. In particular Dr Richards wanted recognition for the volunteer medical orderlies – men he described as friends and colleagues who served alongside him and whose services were absolutely invaluable to the hospitals up and down the railway.

During an interview he was asked what were the attributes he believed made for survival:

1) Mateship – he believed it was an Australian characteristic looked upon with wonder by British, Americans and Dutch.

2) Courage – in particular the courage of medical orderlies. Those who volunteered to care for cholera patients and risked their lives to look after mates. The men who volunteered to remain behind with the dying when the work forces moved on.

Those who risked their lives to go outside the wire seeking urgent food and medicine for their mates.

3) Innovation – a quarter of the Australian Force “were ‘bushies’ to whom you could give a pair of pliers and a piece of fence wire to solve so many problems” said Richards. Richards also included their city cousins who had survived the great depression and learnt self-reliance through hardship.

4) Sense of humour – during the darkest of moments, there would always be a witty remark or sometimes a voice from the back row.

The Rakuyo Maru Party was made up from ‘A’ Force men who had survived working on the railway from October 1942 to end of 1943. They were taken to Saigon to be shipped to Japan. This did not happen as the American submarines had successfully blockaded Japanese shipping sailing from this area.

There was a large group of British POWs who had been in Saigon for some time. Their circumstances were luxurious compared to conditions on the railway line.

Their wooden huts even had electricity! Some senior officers came to Rowley and other senior officers asked them to stop the Australians from spreading stories and fear to the Brits. The Brits obviously did not believe the stories of survival told by the Australians.

It was at this point Rowley Richards realized that if these British POWs did not believe them, how would they ever be able to share their lives and experiences when they got home?

He knew then, they could only ever share their feelings and thoughts with those who had been there. Nobody else would ever completely or fully understand.

The ‘Rakuyo Maru’ Party had to return by rail via Bangkok to Singapore to sail to Japan. On 12 September 1944, ‘Rakuyo Maru’ was attacked by American Submarines in the South China Sea. The ship took 12 hours to sink, but it took days and days of total despair for most of the survivors now covered in oil, clinging to debri, lifeboats deserted by the Japanese and temporary rafts without food and water to tire, go mad or slip away with fatigue and drown. Only a few were saved by the same submarine crew that attacked them days earlier.

Rowley Richards was one of a group who were picked up by the Japanese Navy including 2/4th’s Bert Wall. Richards spent the remainder of the war at Sakata,Yamagata Prefecture, in Japan’s cold northwest.

‘On morning September 13, Nissho Maru, Kasuga Maru, CDV No. 11 and sub-chaser No. 19 were dispatched from Hainan and rescued the survivors of Kachidoki Maru. The three vessels which had been relieved from MANO-03 escort were also ordered to rush to the waters where HI-72 had been attacked. Of the survivors of Rakuyo Maru, the Medical Officer, Captain Roland Richards was on one of a group of four boats, and another group of seven boats on which Brigadier Varley and Colonel Melton were drifting, remaining within the sight of each other. On the morning of 14 September, a Japanese CDV appeared, and to the great surprise of the survivors, this CDV No. 10 rescued 157 POWs of Dr. Richards’ group. According to his statement, before they were rescued, they had heard gunfire. The survivors aboard those seven boats, including Brigadier Varley and Colonel Melton, were never seen or heard from again.’

‘On morning of 14 September, a Japanese CDV appeared, and to the great surprise of the survivors, this CDV No. 10 rescued 157 POWs of Dr. Richards’ group. According to his statement, before they were rescued, they had heard gunfire.’

Arrival Sydney

Richards returned to Sydney on an aircraft carrier with 1,000 former Australian POWs many of whom had survived the privations of Burma-Thai Railway. Gordon Bennett came down to the ship to welcome us and launched into a tirade about what a hard time they’s given him when he got back (Feb 1942). That was the type of fellow he was. Most of the fellows just walked away from the parade!

Dr Richards returned to NSW and practising as a doctor.

He died in 2015.

__________

ROWLEY RICHARDS 1916-2015

‘As a POW and medical officer on the Burma-Siam Railway during World War II, Dr Rowley Richards witnessed an unimaginable catalogue of misery, horror, sickness and death and saved countless Australian lives through his heroic efforts tending to men severely weakened by starvation, tropical disease and the systematic brutality of their Japanese captors.’

Throughout this ordeal, he reminded his men, and the officers commanding them, of the importance of hygiene, prevention of illness and first aid. His strict adherence to these principles saved many lives and ensured that no man under his care ever lost a limb to tropical disease.

After the war, despite his considerable achievements, Richards was never interested in self-promotion. Rather he focused his efforts on preserving and honouring veterans’ memories. He was particularly concerned with recognising the volunteer medical orderlies – men he described as friends as well as colleagues – who served alongside him.

Rowley Richards’ war efforts and contribution to medicine were acknowledged at the highest levels.

The starvation, frequent beatings and other cruelties inflicted on him by the Japanese could have led to hatred and bitterness, but Richards proved he could rise above that, making friends with some of the Japanese civilians who helped him during his time as a POW and keeping in contact with them and their families after the war.

Charles Rowland Bromley Richards was born in Summer Hill on June 8, 1916, the son of Charles Richards and his wife, Clive (nee Bromley). Charles was a draughtsman at Sydney’s leading cartographer, H. E. C. Robinson, who drew much of the original Sydney street directory, now known as Gregory’s. Clive was a teacher at the Deaf and Dumb School in Sydney and later a lay preacher at the Adult Deaf and Dumb Society.

Charles and Clive were both profoundly deaf, although they could speak clearly. They raised Rowley and his brother Frank in a strict but loving household and taught them to: “Trust in God and fear no man”.

Rowley’s holidays were spent with his Aunt Linda and her husband Dr Arthur Lewis in Kyogle, on the north coast. As a teenager, Rowley spent much of his free time accompanying Arthur on his rounds at the local hospital. The importance of hygiene and practical first aid were drilled into him.

Rowley attended Summer Hill Intermediate High School and Fort Street Boys High School then entered medical school at the University of Sydney in 1933. Alongside his studies, he served in the 1st Artillery Survey Company in the regular militia, working his way up to become a commissioned artillery officer. After his residency at the Mater Hospital in North Sydney, he was appointed Regimental Medical Officer of the 2/15 Field Regiment (2/15 Field Regiment) in 1940.

In July 1941, he was shipped to Malaya. As various elements of the 2/15 were deployed to challenge the advance of the Japanese Imperial Army down the Malay Peninsula, Richards co-ordinated medical care and supervised his orderlies.

After Malaya fell in February 1942, Richards, aged 25, was incarcerated in Changi camp for three months. He was then deployed to various camps along the Burma-Siam Railway for the next two years. Throughout this time, he kept a secret diary, in the hope it might one day be used in war crimes proceedings.

Writing in tiny script on tissue-thin paper, he meticulously recorded statistical information and medical details from the Malayan Campaign, and from the primitive and brutal prison camps in Singapore and along the Burma-Siam Railway.

In September 1944, after he heard rumours he was to be shipped to Japan as part of a slave labour force, Richards hid a summary of the diary in a bottle and buried it in the grave of a colleague, Corporal Sydney Gorlick. He gave the full version to his friend and mentor, Major John Shaw, who stayed in Tamarkan Camp, in Thailand. Shaw hid it in the false bottom of a billy can and kept it safely until the war ended.

The ship carrying Richards to Japan was torpedoed in the South China Sea and he spent three days lost at sea before his rescue by a Japanese warship. He then spent a further eight months in captivity in bitterly cold Sakata, northwest Japan.

During his time in captivity, Richards endured malnutrition, dysentery, malaria, smallpox and starvation. His ordeal finally came to an end in August 1945, when the Japanese surrendered. He returned to Sydney in October 1945.

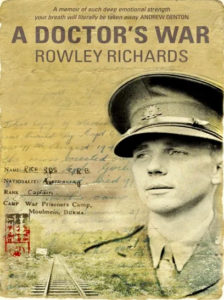

Major Shaw returned his diary to him later that year, and the Directorate of War Graves Services found and returned the buried summary to him in 1947. His diaries and records were used in war crimes prosecutions and also formed the basis for his two books, The Survival Factor (1998) and A Doctor’s War (2005). The diaries are now in the Australian War Museum.

In July 1946, Richards was working as a resident medical officer at St Vincent’s Hospital, Darlinghurst, when he met Beth McNab, a registered nurse. She knew her own mind and was independent and spirited. Richards, who could also be stubborn, knew he had met his match. They married in 1947 and built a house in Balgowlah. Also in 1947, Richards was Mentioned in Dispatches for his war service.

Richards, a firm believer that the most effective committee should have a membership of one, was active in the ex-service community for the rest of his life. He was president of 2/15 Field Regiment Association and the 8th Australian Division Association.

He built a successful and varied post-war medical career, practicing privately in Seaforth as a GP-obstetrician. He was chairman of the St Johns Ambulance Association in 1981, and was medical adviser to the Australian Olympic Rowing teams for the 1968 Mexico Games and 1972 Munich Games. He was honorary medical director of the City to Surf from 1977 to 1998 and honorary medical consultant after that.

In 1969, Richards was awarded an MBE and in 1993 an Order of Australia Medal. In 2003, he received the Australian Centenary Medal. He later was awarded an honorary doctor of medicine degree by the University of Sydney.

He was a foundation fellow of Australian College of Occupational Medicine and Australian Sports Medicine Federation and a fellow of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, the American College of Sports Medicine, and the Australian Institute of Management.

In 1972, with Beth as his assistant, he began his practice in Executive Health in North Sydney. He finally retired in 2000, aged 83.

He and Beth both loved entertaining and cooking. Richards was a keen horticulturalist and his garden was filled with native and exotic plants and flowers. He kept a glasshouse full of exquisite orchids and would always present one to Beth on special occasions.

He and Beth also travelled widely. In recent years he revisited Singapore, Malaya, Thailand, Burma and Japan. In 2011 he revisited Sakata, where he met several descendants of the Japanese civilians who had assisted him and his fellow POWs during the war.

Journalist Andrew Denton provided the foreword to A Doctor’s War, and wrote recently: “Rowley was as good a man as this country has produced”.

Rowley Richards is survived by his son David, daughters-in-law Maria and Lois, and their extended families. Beth died in 2005 and their younger son, Ian, in 2008.

We wish to thank and acknowledge journalist Amy Ripley – Sydney Morning Herald, 27 March 2015 for this fine obituary of Rowley Richards, a doctor held in high esteem by Australian POWs.

Japan says sorry to former Australian POWs

AM / North Asia correspondent Mark Willacy

Posted Fri 4 Mar 2011 at 5:04am, updated Fri 4 Mar 2011 at 7:54am

Former Australian prisoner of war Norman Anderton shook hands with Japanese foreign minister Seiji Maehara in Tokyo. (Yoshikazu Tsuno: AFP)

Japan has apologised to a group of Australian former prisoners of war for the pain and suffering they endured as captives during World War II.

The apology was offered to the five old diggers in person in Tokyo by Japanese foreign minister Seiji Maehara, who told them he was sorry from the bottom of his heart for their treatment.

They came with walking sticks and in wheelchairs, five men the Japanese Imperial Army could not break – not in Changi nor on the Thai-Burma railway.

Once inside the Foreign Ministry in Tokyo, the group’s oldest member, Rowley Richards, 94, sat across the big table from Mr Maehara and he did not flinch.

“The important thing to our members, there are many of them as you know, are looking for an official apology,” he said.

After a 20-minute meeting with the foreign minister the old diggers emerged with something many POWs have been seeking for 66 years – a sincere apology for their suffering and pain.

“As I understood it, it was deep and expressed great remorse for the suffering that was inflicted on us and it was a very moving experience,” said 89-year-old Norm Anderton, who was used as slave labour on the Thai-Burma railway.

“He said to consider it a formal apology from the government.”

Standing next to Mr Anderton was 90-year-old Harold Ramsey. He said before the meeting that an apology would be worthless because it would come from a generation of Japanese who were not the ones who beat and humiliated him.

But after his meeting with the foreign minister, Mr Ramsay’s scepticism had melted somewhat.

“We waited a long time but it was sincere and much better time than when I was here before in 1944 … this is really good, very sincere,” he said.

Of the 22,000 Australian prisoners of the Japanese more than a third died in captivity.

The Japanese government realises time is quickly taking those Australians who survived the horrors of their captivity, so it is vowing to bring more former POWs to Japan to try to reconcile and offer remorse.

“I think we know that to have better future, it is very important to put right what was wrong in the past,” said ruling party member Yukihisa Fujita.

For Mr Richards, who as a doctor treated thousands of his comrades on the Thai-Burma railway, the time has come to forgive.

“I believe very firmly if any individuals hold bitterness, there is only one person who suffers – that’s the person who is being bitter and I’ve often said that if I feel bitter towards the Japanese country, they are not going to fall down on their knees and worry about it.”

Last year the Japanese government offered a similar apology to a visiting group of American former POWs.

Records returned

Foreign Minister Kevin Rudd has welcomed the apology and also thanked the Japanese government for their offer to return historical records of Australian former POWs held by Japan during World War II.

“I welcome their offer which is made in the spirit of cooperation,” he said.

“These index cards were originally offered to Australia by the Japanese government in 1953, but the Australian Government of the time chose not to take up the offer, believing that they would not contain any new information,” Mr Rudd said.

Veterans’ Affairs Minister Warren Snowdon says the Japanese records may shed light on the fate of the members of Lark Force, many of whom were lost when the Japanese transport Montevideo Maru was sunk by a US submarine in 1942.

“The Government recognises that there are families who remain uncertain about the fate of those captured by the Japanese during World War II,” Mr Snowdon said.

“In recent years, the Rabaul and Montevideo Maru Society have maintained interest in the fate of Australian prisoners of war and have pressed the Australian Government to seek access to the card system.”

The records are expected to be housed in the Australian War Memorial.