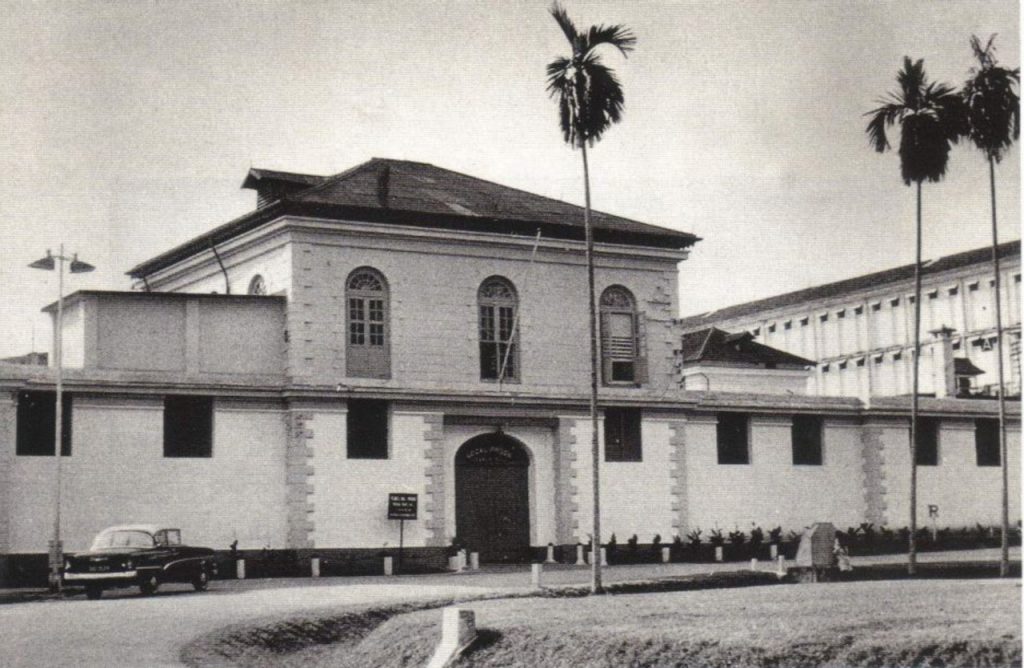

Outram Gaol Singapore

The story of FIVE AUSTRALIANS WHO SHOULD NEVER HAVE BEEN SENT TO THIS HELL-HOLE

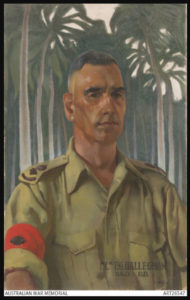

Condemned by Australian Lt-Col Roland Oakes – Adam Park, 1942

At the outbreak of World War 2 Oakes was appointed as a Major with 2/19 Battalion and then given command of 2/26 Battalion (with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel) just as the Japanese invaded Singapore island in February 1942. With the fall of Singapore a week later, Oakes became a prisoner of war and was sent, in May 1943, as second in command of ‘H’ Force, to Thailand to work on the Thai-Burma railway at Hellfire Pass.

Young Australian soldiers felt shame, humiliation and total bewilderment at being taken POWs of Japan with the Allied surrender on 15-16 February 1942. They all marched from Singapore city to Changi.

Most would have thought of escaping. They soon found this not nearly so easy as originally believed.

From the overcrowded Selarang Camp these young Australian men were pleased to move out of the Changi complex to other camps such as the former military barracks 50 km from Changi called Adam Park. The task of Adam Park POWs was to build a shrine to honour the glorious Japanese dead.

Relaxed security at Adam Park provided new opportunities –scrounging food and sourcing other useful items such as parts for radios. There were many partially wrecked houses formerly occupied by British and wealthy Chinese where they were able to source good contraband.

The Australians quietly sabotaged the construction of the Japanese Shrine whenever possible, although the work was hard with POWs virtually acting as human pile-drivers while the Japanese overseers screamed and shouted.

Queenslander Signalman Chris Neilson was a strong willed young man and his best mate Green were always looking for wireless parts. They were approached by a young Chinese man asking what they were looking for. ‘Wireless parts’ replied Neilson. The Japanese had cleverly removed all the master valves rendering the radio sets useless. Approached again by the same Chinese men the two men were told wireless operators were needed for the guerrilla forces in Malaya. Neilson and Green again bumped into the same Chinaman with the same message. They offered the Australians guided passage and plenty of food in Malaya confirming there were a number of British, Australians and Indian soldiers who had escaped capture by the Japanese already with the guerrillas. Besides two radio operators, the guerrillas wanted three mechanical men – truck drivers. He offered safe passage with a guide to Jahore where they would be met by another guide to take them to the mainland.

Back at Adam Park Neilson discussed this plan with three Motor Transport men they knew from SA – Ken Bird, Reg Morris and Bill Goodwin. Neilson began making arrangements and discussed the plan with his immediate senior officer Captain Fred Stahl who provided Neilson with quinine and a code to use if he was every able to make contact by radio with the outside world. They were even provided with information to access arms and ammunition buried in the area after action.

Equipped with a Tommy gun, pistols, compass and quinine the five men made arrangements to leave with their contact assuring them food would be provided at designated points on the journey as well as confirming they would receive some dark Chinese clothing for the escape.

The Australians at this particular time were not guarded as such when they arrived back at Adam Park after a day’s work. The only guards were on the main road coming in so the party skirted around them. Their young Chinese boy was good, leading them single file dressed as coolies emphasising to them to shuffle as the Chinese did, and bow to every sentry on their way with their weapons concealed beneath their sarongs. They walked past unchallenged.

Walking though jungle paths and rubber plantations in total darkness for about 10 miles they arrived about 400 yards from Jahore Strait where they would meet the next guide to take them over the strait to the Malay mainland the following night. The plan was to wait until the regular Japanese patrol boats passed and then set out about 8pm.

At 4pm Bob Green came down with a bad attack of amoebic dysentery. One of their guides went to a nearby village where he was known but was unable to get any drugs – the Japanese had taken everything. The Australians tried an enema with a bicycle pump – but nothing worked. This desperate situation went on for five days. Green became delirious and was by then screaming and raving. On the 6th day the Australians sat and discussed their alternatives. Green was Neilson’s friend – the men knew Green would give them away sooner or later. As Neilson saw it, they had two choices knock Green on the head and go on or go back to Camp. With the toss of a coin the decision was made. The escape party would return to Adam Park.

They managed to return to Adam park without being detected by the guards and got Green to the Medics – they had to hit him a few times to quieten him. The four immediately planned to exit with a replacement technician and go out again that night.

The escape party had initially been covered up for three nights before the Japanese were informed five men were missing. The Camp had been paraded, the POWs counted but no officers were physically beaten.

Below: Chris Neilson 1940 – we acknowledge ABC Radio National ‘Earshot’

Neilson, C. (2021). Chris Neilson. Retrieved 7 October 2021, from https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/earshot/neilson/6082874

When the Australian Commanding Officer Lt. Col Roland Oakes heard the escapees had returned he ordered them to parade before him. The escape party were amazed and totally shocked to learn their own CO had decided to turn them over to the Japanese for punishment. Oakes told them ‘I am not prepared to risk my life or the lives of the men in this camp for the sake of a few irresponsible men who try the impossible’.

Neilson argued ‘You can’t hand us over the Japanese to lop our heads off’.

Oakes replied ‘I’ll ask the Japanese if I can try you and I’ll be severe’.

Neilson argued ‘They wont take any notice of you. It’s your duty to help us and it’s our duty as POWs to escape’.

Years later Bird confirmed this conversation had taken place, adding Oakes claimed he was ‘building up confidence with the Japanese’.

Bird told him ‘You silly bastard.’ Oakes was terrified of them (the Japanese) that’s what it was, said Bird.

Another escapee Reg Morris testified in a statutory declaration in 1946 to AWM ‘Colonel Oakes saw fit to hand us over to the Japanese’.

The party of exhausted men were then allowed to get some sleep while waiting for the Japanese response.

Neilson said “I was woken up with a boot in the ribs.”

The Kempeitai, Japanese military secret, police arrived. In the presence of Col Oakes and Captain Stahl, the five men were handcuffed and chained, tied together and pushed from the room with their legs locked with leg-irons. Every Japanese guard in the camp had their head bowed (in fear) as the prisoners were escorted out of Adam Park.

As the men were being dragged into a truck, Neilson managed to speak to the adjutant, his signals officer Capt Stahl and told him

“If they lop me I’ve got three brothers in the Army, and if any of you make it out I want you to drum them that this bastard (Oakes) turned me in for doing my duty and they will fix him.”

Stahl responded “I don’t think you’ve got much chance. We’ve been reading orders from the Japanese twice daily for the last five days that anyone caught attempting to escape will be publicly executed.”

This incident would have enraged the Aussies in the Camp.

An Australian Officer reporting Australian soldiers, POWs to the Japanese!

What about Capt. Stahl who initially approved their escape providing quinine and weapons?The arrested men must have felt a huge sense of betrayal.

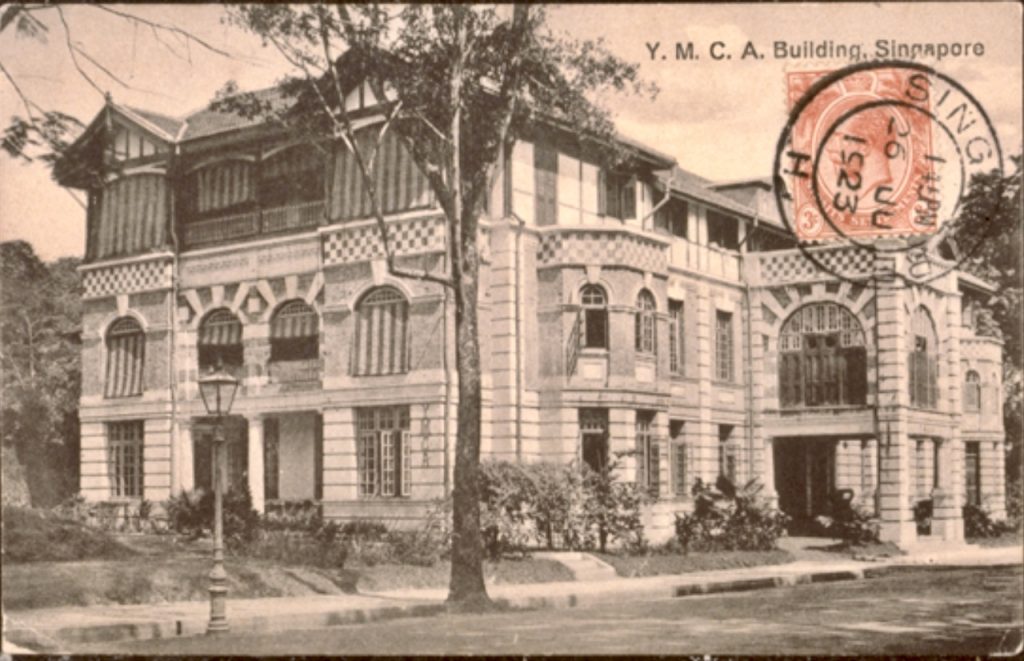

The Kepitai threw the Australians into their truck and they were driven to the YMCA building where Kempitai interrogations began. The group made a decision to plead ‘they were out scrounging for food’ and not escaping.

Please read the War Trial of Capt. MIKIZAWA Koshiro

SX6846 Pte. Bird, K.J. 2/2 M.T

SX2654 Dvr Goodwin, W.C. 2/2 M.T

SX9427 Dvr Morris, R.L 2/2 M.T.

VX45936 Signalman Green, R.H. Signals 8 Div

QX3890 Signalman Neilson, C.H.E. Signals 8 Div

Below: The YMCA building which became HQ for Kempitai.

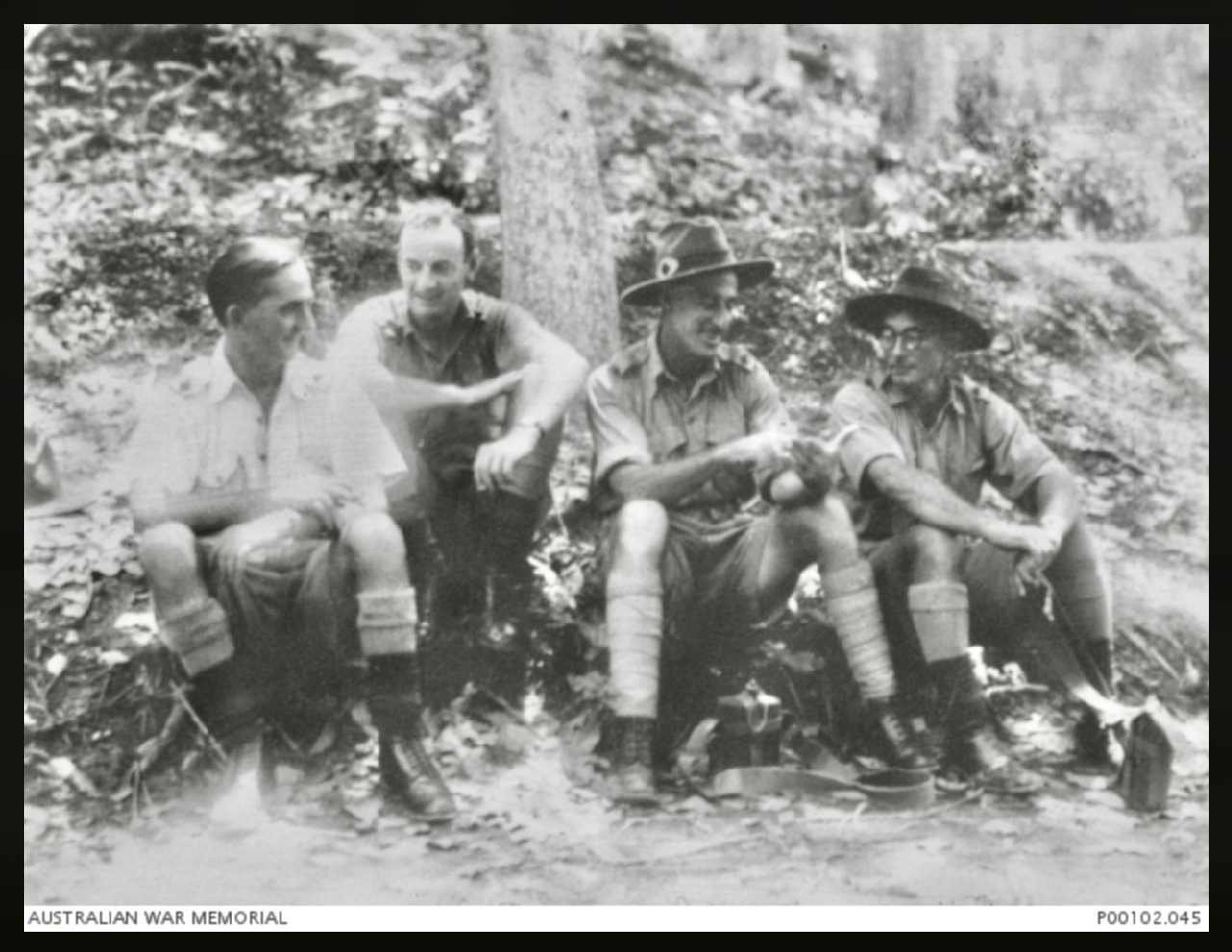

An informal group portrait of Company Commanders of 2/19th Battalion on reconnaissance near Seremban, sitting on ground talking. Left to right: NX34993 Major (Maj) E. H. J. (Bert) Bradley, `C’ Company, killed in action on 12 February 1942; Maj T. G. (Tom) Vincent, `D’ Company, who was awarded the Military Cross (MC), and killed in action on 9 February 1942; 3rd from Left Lt Col R. F. (Roley) Oakes, `A’ Company; Lt Col Charles Anderson, Commanding Officer. Lt Col Anderson was awarded the Victoria Cross (VC) for his leadership in the Malayan campaign.

NSW 2/19th Officers embarking for Malaya L-R: Major R.F. Oakes, Lt-Col D.S. Maxwell, Capt. C.H. Cousens

If a prisoner became seriously ill at Outram Road, it was more convenient for the Japanese to send them back to Changi to recover in hospital rather than have the prisoner die in their gaol.

Below: John McGregor, 2/4th MGB Please read further about McGregor

John McGregor of 2/4th became became seriously ill with dysentery, beri beri, pellagra and scabies. The Japanese guards enjoyed this white man fighting to stay alive because that was what McGregor did. Unable to stand, McGregor was finally and unexpectedly transferred to Changi on 19 July 1943 with three other Australians and four Englishmen. The prisoners were led out of the gaol and into a truck. The near corpses were dumped on the hot bitumen at Selarang Barrack Square where the men remained until somebody noticed an out-of-place heap in the Square. On close inspection he found 8 skeletons lying in filthy rags, unwashed, with unkempt hair and quickly notified hospital staff.

The doctors quickly picked up each man carried them to the hospital section where others gathered around to assist to clean and shave these human wrecks amongst whom was a skeletal man named John McGregor. He was first offered three boiled lollies by Major Adrian Farmer from Perth who apologised for not having something better to offer. McGregor then broke down, overcome by kindness. He had come to heaven from a hell that only those who had been there would fully comprehend.

The medical staff were to soon isolate the four men from their well-wishers concerned as much about their fragile mental health as their physical health. Their faces were hidden beneath shaggy masses of matted, filthy and vile-smelling hair and their bodies had scabies, infected sores, badly swollen limbs, dry, parched and cracked skin.

McGregor underwent an operation for haemorrhoids, pterygiums (benign growth on conjunctiva) on both eyes were removed in an effort to boost his failing eye sight (McGregor became blind soon after returning home) and fed the best foods Changi could provide to fatten him up in preparation of returning to Outram Road Gaol. McGregor knew he was on borrowed time – a Japanese medical officer would visit every week looking for those POWs fit enough to return to their sentences.

Of course the Australian doctors did all they could to delay the men’s return, blinding the Japanese with medical jargon stressing their patient’s ill health. McGregor’s weight increased over several months. His doctors played on his failing eye sight. When the Japanese asked if McGregor’s eyesight would improve and was told no, they said McGregor may as well return to Outram Road.

McGregor’s former cell neighbour Chris Neilson also arrived at Changi blind. Neilson had better luck and remained at Changi for just over 12 months. His eyesight returned somewhat after being at Changi but lived the rest of his life without central vision in his left eye.

According to Neilson whenever the Japanese medicos came the Australian doctors busied themselves to find ways to keep the prisoners. The men lay out in the hospital verandah were it was very hot and not in the ordinary wards and never attended concerts parties, etc. They trained the men to control their reflexes to prevent their legs jerking or jumping up when the Japanese hit them in the right spot. With sufficient warning they would inject something to blow up the scar in Neilson’s eye or to make the men sweat to simulate malaria.

Changi was most fortunate to have many highly experienced and well trained doctors – simply because the 8th Division had been allotted two field hospitals in anticipation of returning troops from the Middle East to build up the number of combatant troops in Singapore.

In his book ‘Stubborn Buggers’ Tim Bowden, an acclaimed oral historian, broadcaster, radio and television documentary maker and author, wrote

‘Somehow the doctors seemed to be more successful at keeping Officers in Changi and most never returned to Outram Road, whereas other ranks did return to the Gaol.’

Medicos conspired to keep at least two Australian officers at Changi, John Wyett (author of ‘Staff Wallah’ see below) and Macalister had bones deliberately broken in their feet. Macalister recovered sufficiently and was the only officer to return to Outram Road but Wyett did not.

At Changi Chris Neilson was moving about freely when the Japanese unexpectedly ‘dropped in’ and was caught out. His was immediately ordered to return to Outram Road in late 1944. The guard was about to march him away when an Englishman called out to him. Neilson told Bowden he will never forgot the conversation. The Englishman yelled out that he had a mate at Outram Road – ‘one of a group that tried to escape through Burma. Most of the group were executed except his mate and another.’ He asked Neilson to pass a message to his mate that he was alive and well.

The ‘madly’ brave Neilson (I describe him as mad because he forever agitated the guards knowing he would be punished and bashed) pushed the Japanese guard aside – an especially brave move – walked over to the Englishman. Neilson told Bowden pushing aside the arrogant Japanese ‘threw’ the guard. So obsessed with their own power, the guard couldn’t comprehend being pushed by a prisoner. Neilson told the Englishman to give him the details fast ‘because the Japanese bloke was waiting to belt the piss out of him.’

The Englishman introduced himself as ‘Tich’ and was one of a group working on the Burma side of the railway – most of them came down with cholera. Tich said his mate thought he had died, but when the British said they could no longer carry him he was indeed lucky because a group of Australians passing through carried him to a bush hospital where he survived. ‘Tich’ and his mate had grown up together in London. It was vital his mate knew Tich was still alive. Neilson confirmed he would do his best and walked back to the Jap guard who had pulled his sword out.

The Australians watched for about four minutes expecting Neilson to lose his head. Neilson said he knew the guard wouldn’t touch him because he had to return Neilson to Outram Road or else the guard would lose his head for failing to do so. Instead the guard put the sword back into the scabbard, removed his belt and severely belted Neilson who lost a tooth and had his nose broken (which had to be reconstructed after the war). In the truck, Neilson was handcuffed so tightly his hands puffed up and on arrival he was placed in black punishment cells for a month.

When he got out of solitary Neilson found a very different Gaol to the one he had left behind more than 12 months earlier – solitary confinement had ended. There were too many prisoners now so there were 2-3 men per cell leaving barely sufficient room to lie down but at least there was somebody to talk with. The food was only slightly better and there were now opportunities to get out of their cells on work parties. Neilson was able to wrangle his way into these work parties.

It was 30 years before Bowden published ‘Stubborn Buggers’. His interviews were heard on ABC radio and recordings made and sold. ** He was asked who was the most interesting/fascinating person interviewed – a very challenging question indeed. Bowden was gracious and replied former POWs were ordinary men who lived through and survived extraordinary lives at Outram Road Gaol and other places. However Bowden wrote it was Chris Neilson who at Outram Road – slowly starved to death, confined in a solitary cells the prisoners forced to sit to attention all day on concrete floors forbidden to talk. They were bashed by guards if they failed and for many guards it was a game of sneaking up on the men and catching them out.

Neilson claimed he survived by goading his gaolers verbally and mentally, resulting in being bashed, sometimes severely. It was a form of mind games. Nelson claimed his actions broke the monotony.

During his ‘Survival’ radio documentaries Bowden titled Neilson ‘Just One Stubborn Bugger’ – this was Neilson’s personal approach to survival but has to be said was the same for all the other survivors including McGregor.

Neilson said he was not a hero, just one stubborn bugger. “You had to put your pride into it. Make others think you are a hero. He was frightened at times – it was alright to be frightened – but don’t let any other bugger see. That is the secret. It was alright to be frightened, he had been frightened, but he was the only bugger who knew it.”

Below: Neilson and Tim Bowden

We wish to acknowledge ABC Radio National for this photograph.

Neilson was one of the POWs who returned to Outram Road Gaol in an effort to identify the worst Japanese. But most had gone, replaced by others.

Returning to Australia, Neilson was 14 months in hospital, and obviously returned from time to time. He had continuing dysentery, a perforated bowel, depressed fracture of the skull and had picked up hepatitis at Singapore before coming home. The psychological problems Neilson and all POWs faced continued most of his life. Neilson had three brothers who had all served in AIF. It was three years before he was able to talk about his experiences. Like most POWs he sought out comrades from time to time. It was where they felt safest and secure.

Four years after retuning to Australia Reg Morris presented Bird with a copy of a paper proving Col. Oakes had turned the five Adam Park escapees over to the Japanese.

Historian and author Don Wall was delighted to receive a copy – he knew the facts of the escape and betrayal but required hard evidence. Driver Reg Morris had made a sworn statement in May 1946 (to AWM);

Oakes had questioned the men on their forced return to Adam Park and ‘saw fit to hand us over to the Japanese’.

No official action was ever taken against Oakes for the betrayal of his own men.

Neilson didn’t need to see any evidence and harboured a severe resentment at what had happened. He acquired a gun and in time he found Oakes living on a property in Queensland and where he then staked out the house. A youngish woman and small children changed his plans – he realised Oakes had a second marriage. Neilson waited until Oakes appeared and shouted to him he planned to shoot him for his betrayal of the Adam Park escapees but had seen his young wife and children.

** Australians Under Nippon. (2021). Retrieved 7 October 2021, from https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/archived/australians-under-nippon/australians-under-nippon/8238812

‘Prisoners of War: Australians Under Nippon’ 16 part series by Tim Bowden, ABC Radio 1984.

And ‘Survival’ 10 part series by Tim Bowden, ABC Radio 1987.

Tim Bowden ‘Stubborn Buggers’ published by Allen & Unwin 2014.

John McGregor ‘Blood and the Rising Sun’ self published Sydney 1980.

Don Wall ‘Sandakan: The Last March’ self-published Sydney 1998

John Wyett ‘Staff Wallah’ published Allen Unwin Sydney 1996

Lt.Col Oakes was the Australian CO with ‘H’ Force Thailand.

The Force Commander was Lt-Col HR Humphries of Royal Artillery, his second in command was Lt-Col Oaks.

‘H’ Force was initially an all-Australian force under the command of Lt-Col R.F. Oakes.

‘H’ Force HQ was at Tampie and the work Force were in camps along a 20 km stretch of railway line between Tonchan and Hintok.

Major Bert Saggers from 2/4th was his second in command and in charge of the group’s pay and records.

Please read further about ‘H’ Force.

Oakes did not stand up to the Japanese – he did not wish to have his face slapped – the usual treatment for Officers who questioned the Japanese Commanders. Oakes was quite fearful of the Japanese. He preferred to walk away and it was said he spent most of his day in his tent. The Japanese would have known Oakes was weak and would not have respected him.

One wonders if the Adam Park incident was in fact known about at Changi HQ – would Oakes have been given the role of CO of the Australians with ‘H’ Force?

We will never know, they may well have known and was the reason he was sent. Just as Weary Dunlop and Roaring Reg Newton were earlier sent to the railway because they stood up to Changi’s Australian CO Major General Frederick Gallagher known as ‘Black Jack’ Galleghan.

Five months after the Surrender on 21 July 1942, Galleghan took over Australian leadership at Changi when his commanding officer Australian Major General Cecil Arthur Callaghan, and British Malaya Command Lieutenant General Arthur Ernest Percival were sent by the Japanse to Mukden in China. ‘Black Jack’ was promoted from Lt. Col to GOC AIF, an inherited position because of circumstances.

Galleghan was a contentious choice. He was an uncompromising authoritarian and founded his leadership style upon regulation, order and discipline. He had an abrupt manner and his leadership style had antagonised AIF HQ. It took the intervention of former Prime Minister Billy Hughes at the beginning of the war, to secure his appointment at battalion level in the Second AIF.

‘Galleghan’s refused to acknowledge the limitations of his power in captivity, and the reality of his conditions, meaning that he struggled to achieve leadership legitimacy let alone followership amongst the men under his command‘

His men from 2/30th Battalion admired and respected him however others saw him s a tyrant because of his determined enforcement of discipline in the camp.

He ran Changi as if it were not a POW Camp and war-time – i.e. with the same stringent rules as a normal camp – forgetting that the men were living on limited food intake, and mostly working, many had returned from working on the railway and were often physiologically ill as well as physically. The POWs did not enjoy the same food as their officers, they were always hungry – hence the reason they were always searching for food./

‘Black Jack’ dressed immaculately every day and expected every POW to maintain the same standard.

Under Galleghan the crime rate increased. He was incensed and embarrassed with the scrounging by Australians. Had the POWs been given a larger slice of Changi’s food they would not have been continually scrounging.

There were a huge number of officers at Changi. Idle men with little to do Changi was filled with jealousies and gossip. Initially the officers each had their own batman. Later when there was a shortage of labour, the Japanese included many batmen in their work parties out of Singapore and sometimes in Singpore.

POWs returning to Changi Camp likened it to a ‘holiday camp’ compared to Camps on the railway.

Below: ‘Black Jack’ Galleghan

Roland Frank Oakes (1896–1986)

by Garth Pratten

This article was published:

-

in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 18 , 2012 and online in 2012