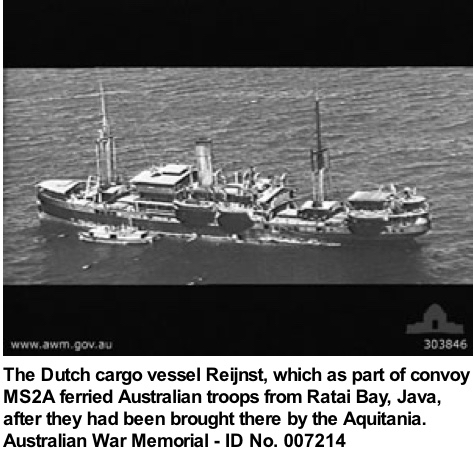

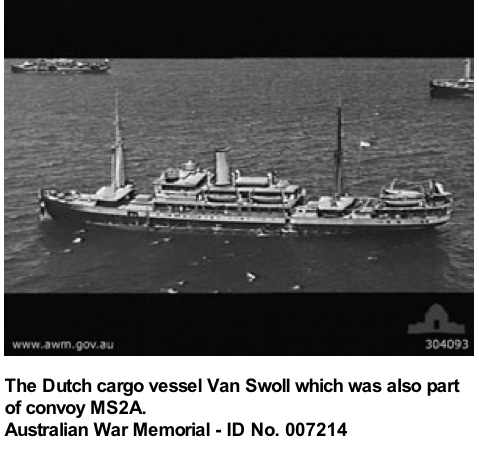

RMS ‘Aquitania’ transported nearly 4,000 Australian troops from 8th Division including the 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion to Ratai Bay in the Sundra Straits where it anchored on 20th and 21st January 1942 to allow the men to be transported to Singapore onboard Convoy MS2A which included Dutch ships Reijnst, Van Swoll, Both, Real, Sloet van der Beele, Van der Lijn and Taishan with naval escorts and arrived at Singapore on 24th January at 1030 hours.

It was considered too dangerous for such a large ship like ‘Aquitania’ to enter Singapore harbour.

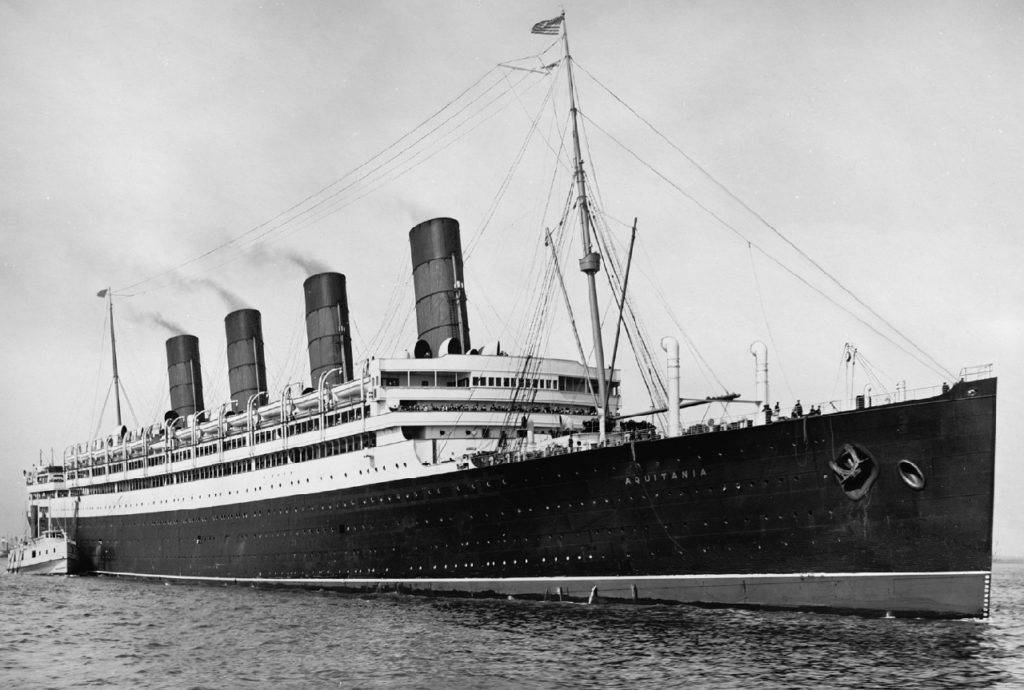

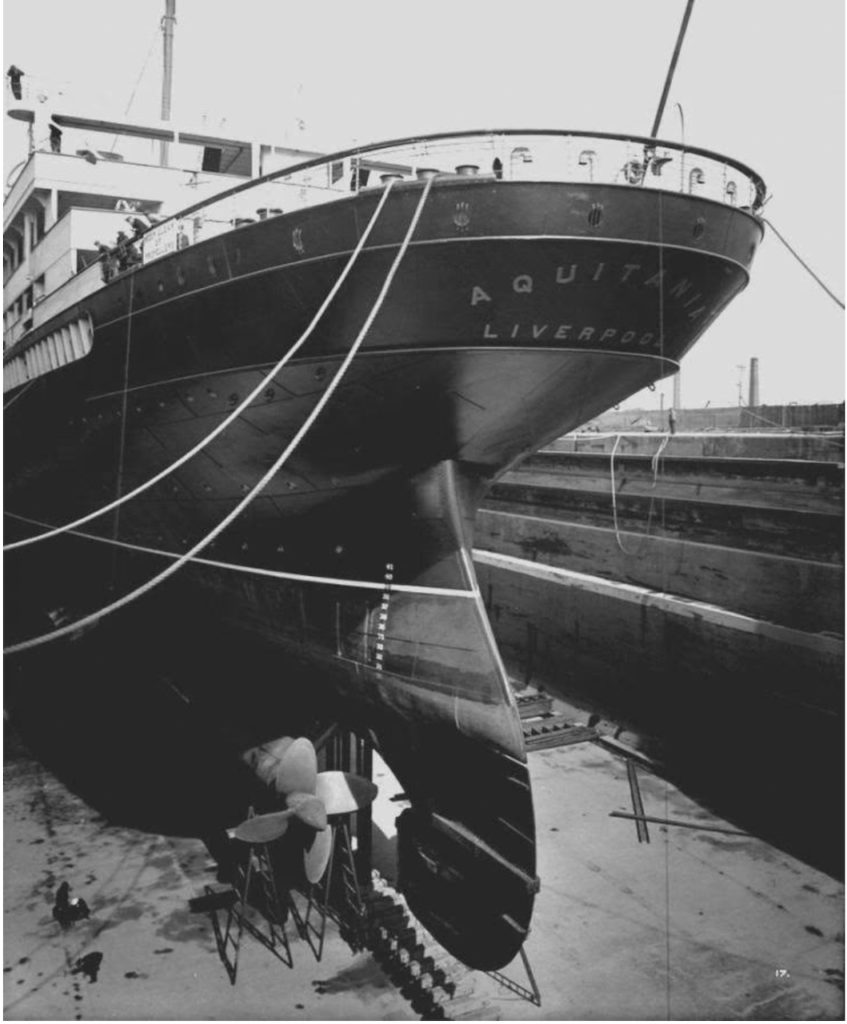

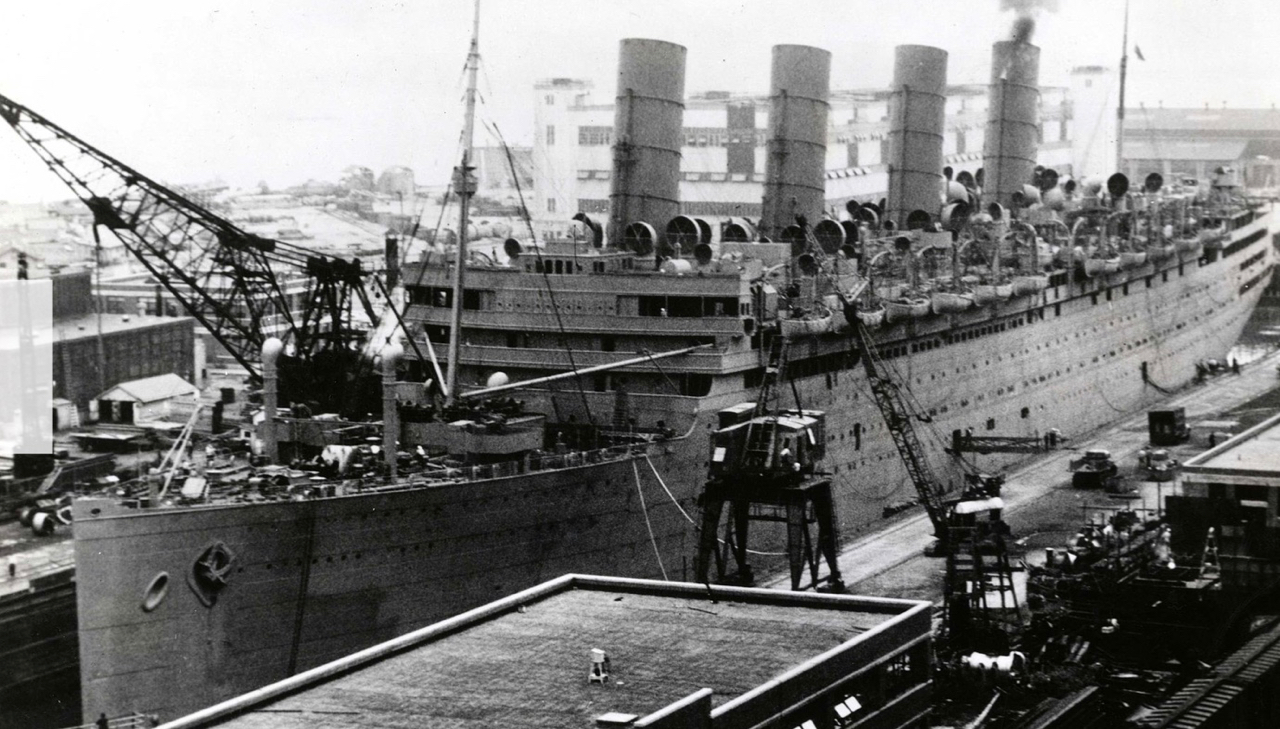

RMS ‘Aquitania’ was a British ocean liner from the Cunard fleet serving from 1914 to 1950 and was the last surviving 4-funnelled ocean liner. She was the third in a line of Cunard’s trio of luxury express liners.

Unlike other liners with four funnels, ‘Aquitania’ did not have a dummy funnel; every funnel was utilised in venting steam from boilers. ‘Aquitania’ was built larger and wider than her sister-ships ‘Lusitania’ and ‘Mauretania’.

The ship displaced approximately 49,430 tons of which the hull accounted for 29,150 tons, machinery 9,000 and bunkers 6,000 tons. She was under construction when ‘Titanic’ of the White Star line sank. White Star and Cunard were rivals and ‘Aquitania’ was built in response to ‘Titanic’.

She served in WW1 as a troop carrier and hospital ship and returned to the transatlantic route in 1920. She earned the nickname of “Ship Beautiful” by her passengers. She was also known as the ‘Lucky Ship’ and enjoyed a long life compared to ‘Titanic’.

She was about to be retired in 1940 when WW2 broke out and she served as a troop carrier until 1947, transporting Canadian, Australian and New Zealand troops.

‘Aquitania’ was retired in 1949 having serving 36 years as a passenger liner. She was scrapped in Scotland in 1950.

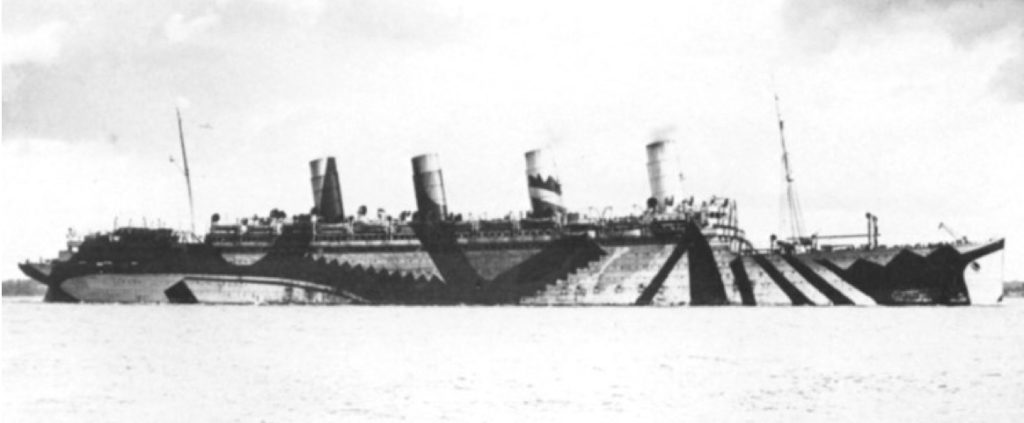

Above ‘Aquitania’ prepared for WW1

‘Aquitania’ 1942 in Boston

Above HMAS ‘Canberra’ the naval escort to ‘Aquitania’ sailing from Fremantle 16th January 1942 to Ratai Bay, Sundra Straits.

Please read about the Incident at Fremantle’s Gage Roads when Aquitania anchored for one night on her journey to Singapore and the 2/4th men who were AWL

Also the stowaway found on Aquitania on route to Singapore

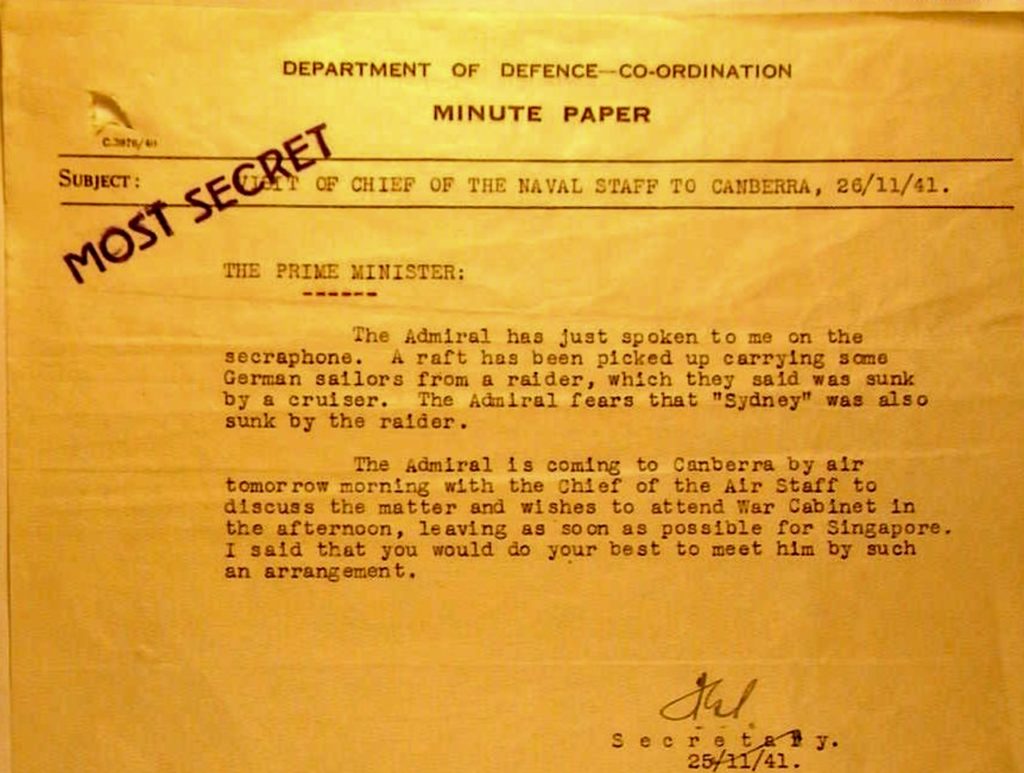

‘AQUITANIA’ PICKS UP 26 KOMORAN SURVIVORS 26 NOVEMBER 1941

On 19 November 1941 HMAS Sydney and German Ship Komoran encountered each other by sheer chance, approximately 106 nautical miles (196 km; 122 miles) off Dirk Hartog Island. The single-ship action lasted half an hour, with both ships destroyed.

HMAS Sydney was quickly disabled and all 645 Australian crew were lost.

Disguised as a Dutch merchant vessel, Komoran used the advantage of surprise to have Sydney close and enable Kormoran to bring maximum firepower to bear on Sydney

Below: Sydney

Just before 0600 on Sunday 23 November, a cabin boy on ‘Aquitania’ saw a low-lying raft bobbing on the pearly morning sea. The 26 men on the poorly equipped raft had seen her long ago, and were waiting anxiously for a sign that they had been noticed. (Komoran’s Captain, Detmers saw the troopship from another raft but did not make their boat’s presence known, as he hoped to be recovered by a neutral ship.)

The ‘Aquitania’ picked up these Kormoran survivors at 24°35’S, 110°57’E,4 200 kilometres off the coast of Western Australia. ‘Aquitania’ maintained radio silence continued her journey and did not report the discovery until her arrival off Wilson’s Promontory on 27 November.

Soon after, on 24 November British Tanker MV Trocas picked up 25 Germans in another life raft, and sent a coded signal to this effect to Navy Office. Later, another lifeboat landed, with 46 men, at Quobba Station, north of Cape Cuvier. This boat was one of two which were found along the coast north of Carnarvon, the other with 57 men.

Once the Navy Office had received news from Trocas that she had rescued survivors from a ship, it is believed this was the first time they learnt about Sydney and a full scale search was mounted, which included ‘every available aircraft in Western Australia’.

The search for Sydney began 24 November 1941. The search was coordinated by Captain Farquhar-Smith, District Naval Officer, Western Australia, who had ‘operational control over Sydney when she was working out of Perth or Fremantle … He was the one who initialled the search action so he obviously had some operational control responsibility of the ship. He initiated search action once [Sydney] was missing and he also reported back to the Chief of Naval Staff and to the navy office.

Sydney departed Fremantle 11 Nov 1941 for Singapore with transport SS Zealandia sailing to Sunda Strait, where the troopship was handed over on 17 November to HMS Durban. Sydney then turned for home and was scheduled to arrive in Fremantle late on 20 November. When she had not returned by 23 November, the concerned Naval board signalled her. There was no reply.

318 of the 399 crew aboard the German ship were rescued and placed in prisoner of war camps.

The raider Komoran had been operating in the Atlantic during which time she sank seven merchant ships and captured an eighth. Komoran sailed to the Indian Ocean in late April 1941. Only three merchantmen were intercepted during the next six months, and Kormoran was diverted several times to refuel German support ships.

The raider was carrying several hundred sea mines and was expected to deploy some of these before returning home in early 1942. The captain planned to mine shipping routes near Cape Leeuwin and Fremantle, but he postponed this after detecting wireless signals from a warship (Australian heavy cruiser HMAS Canberra) in the area. Instead, he decided to sail north and investigate Shark Bay.

At the time of the battle, the raider was disguised as the Dutch merchantman Straat Malakka and carried 399 personnel: 36 officers, 359 sailors, and 4 Chinese sailors hired from the crew of a captured merchantman to run the ship’s laundry.

Shortly before 16:00 on 19 Nov 1941 Kormoran was 150 nautical miles (280 km; 170 mi) southwest of Carnarvon. The raider was sailing northwards (heading 025°) at 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph). At 15:55, what was initially thought to be a tall ship sail was sighted off the port bow, although it was quickly determined to be the mast of a warship (HMAS Sydney). Captain Detmers ordered Kormoran to alter course into the sun (heading 260°) at maximum achievable speed (which quickly dropped from 15 to 14 knots (28 to 26 km/h; 17 to 16 mph) because of problems in one of her diesel engines) while setting the ship to action stations. Sydney spotted the German ship around the same time, and she altered from her southward heading to intercept at 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph).

Closing the gap, Sydney requested Kormoran identify herself.

Below: Komoran

Above: Komoran – largest of Germany’s auxuillary cruisers.

‘Kormoran was originally built as the German freighter Steiermark. Following the outbreak of World War II, the Kriegsmarine requisitioned the vessel converting it to a Handelsstörkreuzer (commerce raider). Named Kormoran, and placed under the command of Fregattenkapitän Theodor Detmers, she was the largest of these well-armed, disguised auxiliary cruisers. By November 1941 Kormoran, had sunk ten unsuspecting merchant ships and taken another as a prize.’ Please read further

Above: In 2008 a successful search located Komoran. This photo is of one of her guns, ‘Linda’ with painted with skull and crossbones.

Please read further about the communications and conflict between these two ships from WA Museum

Also read the AWM’s description

Thereafter a battle raged between Sydney and Komoran for half an hour.

The main phase of the engagement ended around 17:35, with Sydney heading south and slowing while Kormoran maintained her course and speed. Sydney‘s main armament was completely disabled (the forward turrets were damaged or destroyed, while the aft turrets were jammed facing port, away from Kormoran), and her secondary weapons were out of range. The cruiser was wreathed in smoke from fires burning in the engine room, forward superstructure, and around the aircraft catapult. Kormoran discontinued salvo firing, but the individually firing aft guns scored hits as Sydney crossed the raider’s stern.

By the end of the 30-minute battle, the ships were about 10,000 metres (33,000 ft) apart. Both were heavily damaged and on fire.

Sydney was proceeding on a south-southeast bearing, apparently not under control. The burning ship consistently lit the horizon until 22:00 with some German survivors stating that the light was visible consistently or occasionally until midnight. Sydney sank during the night; it was originally thought the cruiser exploded when fires reached the shell magazines or torpedo launchers, or took on water through the shell holes on her port side and capsized.

However, after the wrecks were located, it was determined that Sydney was under limited control after the battle, maintaining a course of 130–140 degrees true at speeds of 1.5 knots (2.8 km/h; 1.7 mph). The ship remained afloat for up to four hours before the bow tore off and dropped almost vertically under the weight of the anchors and chains. The rest of the ship sank shortly afterwards and glided upright for 500 metres (1,600 ft) underwater until it hit the seabed stern-first.

Kormoran was stationary, and at 18:25, Detmers ordered the ship to be abandoned, as damage to the raider’s engine room had knocked out the fire-fighting systems, and there was no way to control or contain the oil fire before it reached the magazines or the mine hold. All boats and life rafts were launched by 21:00, and all but one filled. A skeleton crew manned the weapons while the officers prepared to scuttle the ship.

Kormoran was abandoned at midnight; the ship sank slowly until the mine hold exploded 30 minutes later. The German survivors were in five boats and two rafts: one cutter carrying 46 men, two damaged steel life rafts with 57 and 62 aboard (the latter carrying Detmers and towing several small floats), one workboat carrying 72 people, one boat with 31 men aboard, and two rafts, each bearing 26 sailors. During the evacuation, a rubber life raft carrying 60 people, mostly wounded, sank without warning, drowning all but three aboard.

Total German casualties were six officers, 75 sailors, and one Chinese laundryman.

Read about Komoran’s route from 1940 to 1941

Please go to Sea Museum Sydney to read about the discovery of the wrecks

80 years later the RAN with available DNA were able to name the lone sailor whose body was discovered having sailed in a lifeboat for about 3 months in the ocean before perishing.

He was Thomas Welsby Clark aged 21 years

Below: Komoran survivors

SURVIVORS FROM GERMAN RAIDER ARRIVE IN AUSTRALIA

The information has been copied from an archive copy of the Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton) Thursday 4 December 1941.

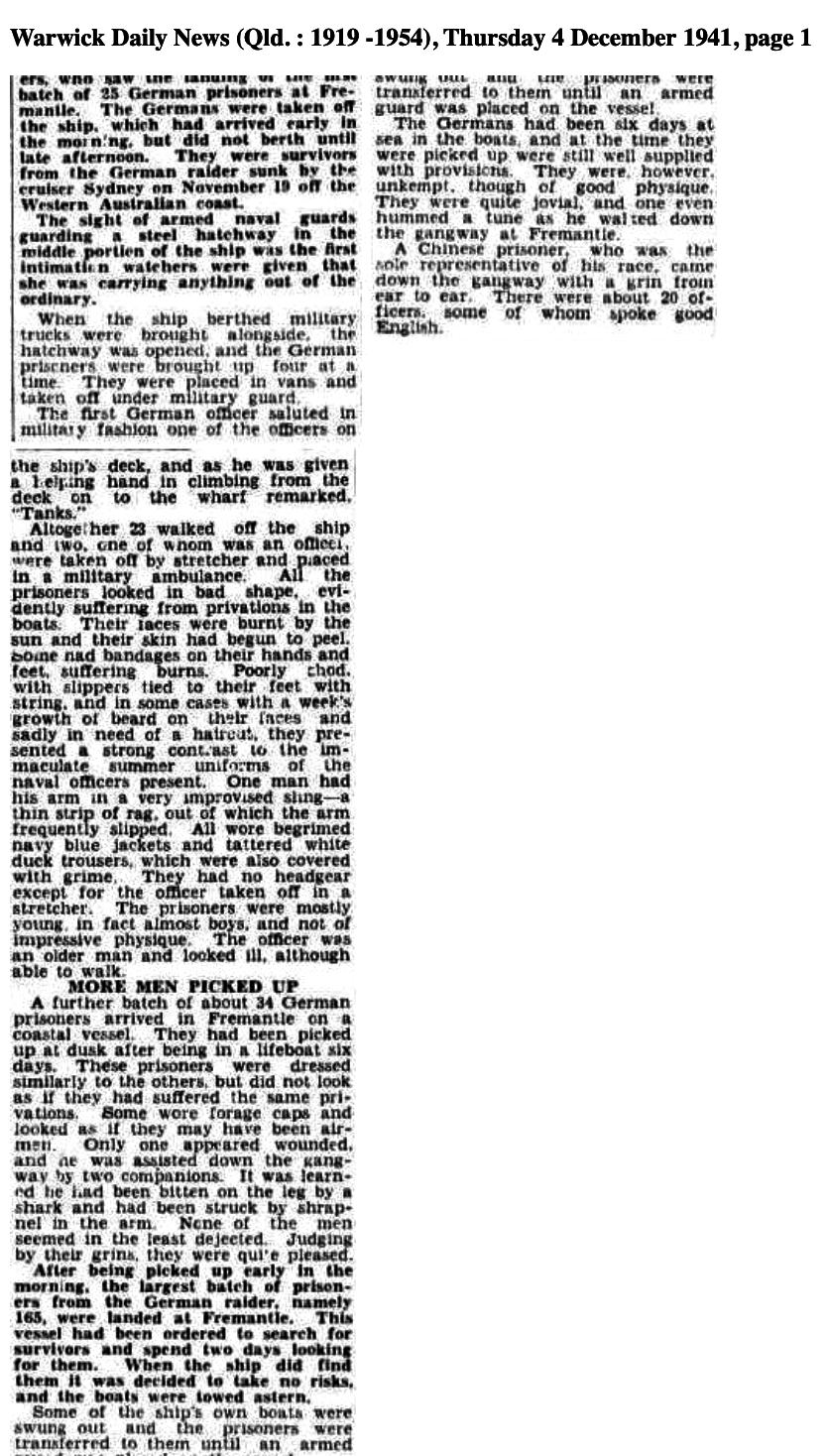

At least two groups of Komoran crew were brought to Fremantle early December. The first batch of 25 arrived in the early morning on a ship, but did not disembark until late afternoon. An armed naval guard was guarding the steel hatchway in the middle of the ship. Military trucks were brought along side and the Germans were brought up on deck four at a time. 23 of the 25 walked off the ship and two were stretchered off to military ambulances.

The newspaper reported this group ‘looked in bad shape and evidently suffered privation in the boat’. Their faces were sunburned and had begun peeling, some had bandages on hands and feet ‘as if suffering burning’. Only the officer who had been removed in a stretcher had a hat and head protection. They were poorly shod with string tied about their slippers on their feet and with a week’s growth of beard on their faces. ‘All wore begrimed navy blue jackets and tattered white duck trousers which also were covered with grime. The men were mostly young boys and not of very strong physique. The officer was older and of impressive physique, he looked ill but was able to walk.’

A further group of 34 crew arrived at Fremantle on a coastal vessel having been picked up at dusk and were in the lifeboat for six days. They wore the same clothes as the earlier group however did not appear to have suffered the same privations. Some wore forage caps as if they may have been airmen. One appeared wounded and was assisted down the gangway by two companions. It was learnt he had been bitten by a shark on the leg and was also suffering shrapnel wounds to his arm.

‘None of the men seemed dejected, in fact judging by their grins they were quite pleased.’

LARGEST GROUP

The largest group of 165 men had been picked up in the early morning. The vessel which found them was ordered to look for survivors and had spent two days doing do.

When the ship did so it was decided to take no risks and the lifeboats were towed astern, the wash from the vessel swamped the lifeboats but still the Germans were not taken on board. Some of the ship’s own boats were swung out and the prisoners transferred to them until an armed guard was placed with them. When picked up the prisoners still had provisions with them. Although unkempt, the men were of good physique and appeared jovial with one even humming a tune as he walked down the gangway at Fremantle.

There were about 20 officers who spoke good English. There was one lone Chinese who exited down the gangway with a grin from ear to ear.

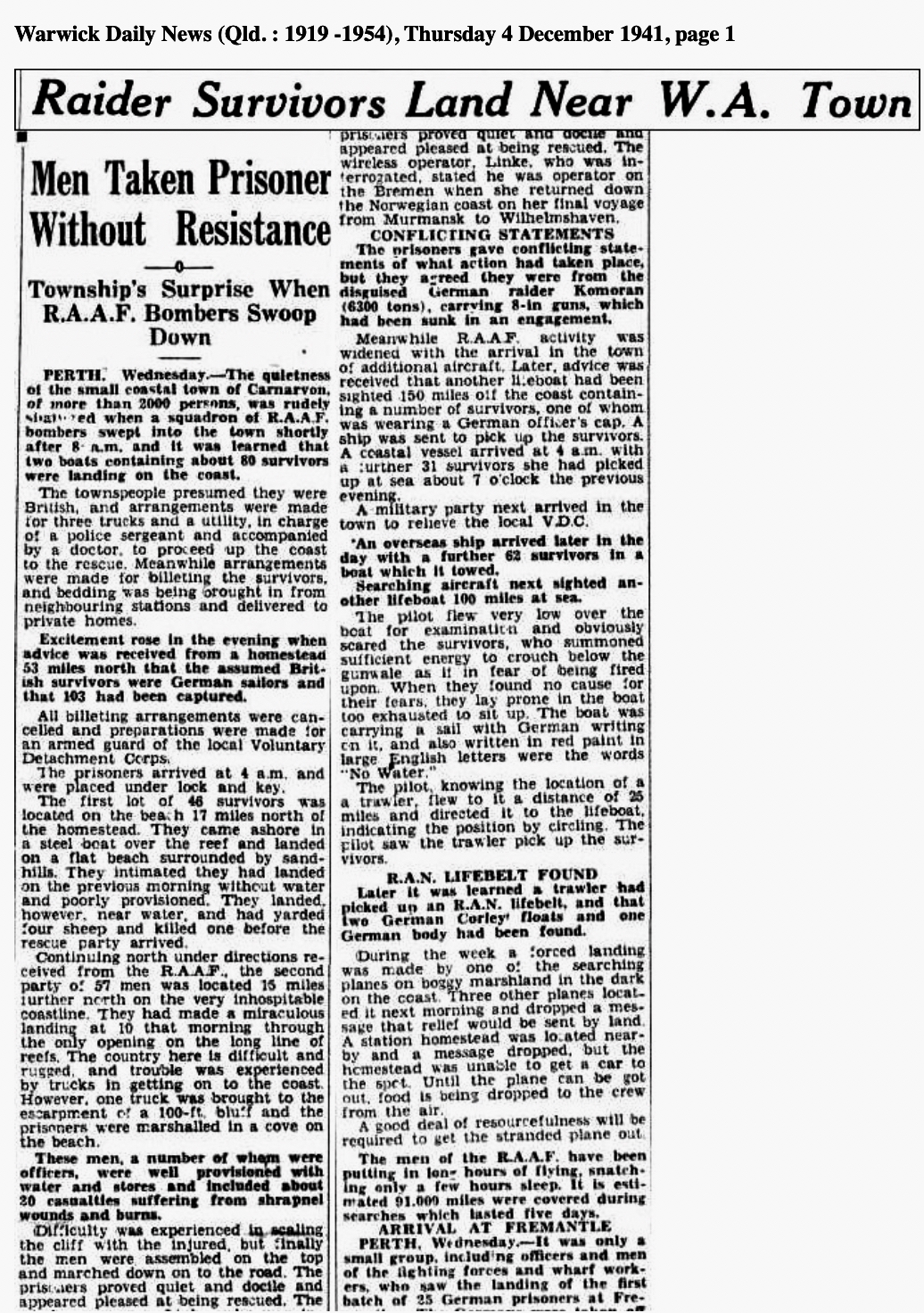

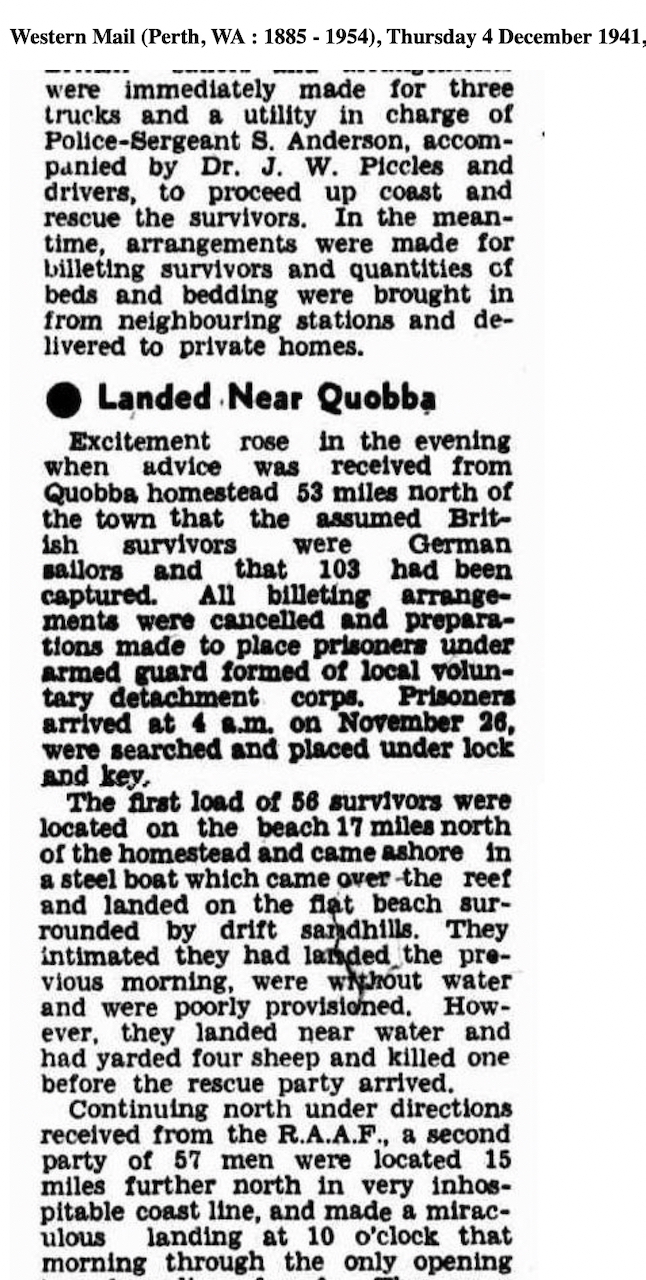

‘The small coastal town of Carnarvon with a population of less than 2,000 was excited when a squadron of RAAF bombers swept into town just before 6.00 am and it was learnt that two boats with about 80 survivors had landed on the coast. The locals assumed they were British. Excitement increased when Carnarvon received confirmation from a station 53 miles away probably (probably Quobba) that in fact the men were German and 103 had been captured. All billeting plans were discarded and preparations made for armed guards from the local Volunteer Defence Corps. The prisoners arrived at 4.00am and placed under lock and key.

The first load of 46 survivors arrived 17 miles north of the Station and came in a steel boat over a reef and landed on a flat section of beach with surrounded by sand hills. The men intimated that had landed without water and were poorly provisioned. They had in fact landed near water and had yarded four sheep and eaten one before the search party arrived.

MIRACULOUS LANDING

Continuing north under the directions of the RAAF the second party of 57 men was located 15 miles further north on an inhospitable coastline. They had made a miraculous landing that morning at 10.00 o’clock through the only opening in a long line of reefs.

With the rugged and difficult terrain the rescuers with their trucks were challenged to get to the men. One truck however was brought to the escarpment of a 100 foot bluff and the prisoners marshalled in a cove on the beach. These men, some of whom were officers were well provisioned with water and food. About 20 men were injured with shrapnel and burns. Although there was difficulty bringing these injured men to the top of the cliff the rescuers succeeded and the Germans assembled at the top of the cliff to begin marching to the road and other trucks.

The prisoners appeared quiet and docile and seemed pleased at being rescued.

They gave conflicting reports about what had taken place but all agreed their ship was the disguised German raider Komoran of 6300 tons, carrying 8 inch guns and had sunk.

RAAF

Additional aircraft arrived in Carnarvon. There had been another sighting of craft 150 miles off the coast with crew, one with a Commander’s cap. A ship was sent to pick them up. A coastal vessel had arrived about 4.00am with 32 survivors who had been picked up about 7pm the previous evening.

A military party arrived in Carnarvon to relieve the local V.D.C.

An overseas ship meanwhile arrived in Carnarvon with another 62 prisoners in lifeboats which it towed. Searching aircraft next found another boat 100 miles out to sea. This boat had a sail with words written in German as well as in English “No Water”. The pilot returned to the trawler guiding them back to the ‘sail’ boat who picked up the prisoners.

It was later learnt a trawler had picked up a RAN life belt, two German Carley floats and one German body had been found.

It was estimated the RAAF covered 91,000 miles during the five-day search. The crew only getting snatches of sleep had worked long hours.

Lucky Germans!

The Japanese didn’t undertake rescue of the POWs when ‘Rakuyo’ Maru sank in South China Sea Sept 1944. They did not need to organise rescue craft, and could have picked up the POWs when they collected their own men from the water.

Group portrait of German Officer prisoners of war (POWs) from the Kormoran interned in No. 13 POW Group at Dhurringile near Murchison. Back row, left to right: Leutnant zur See Rudolph Jansen (Prize Officer); Oberleutnant Heinrich Ahl (Sea Plane Pilot); Leutnant zur See Bruno Kube (Prize Officer); Leutnant zur See Wilhelm Bunjes (Prize Officer); Leutnant Dr Fritz List (Goebbels Propaganda Officer); Leutnant Walter Hrich (UFA Cameraman). Front row: Leutnant zur See Johannes Diebitsch (Prize Officer); Regierungsrat Dr Herman Wagner (Meterologist); Kapitanleutnant Herbert Bretschneider (Executive Officer); Dr Lienhoop.

Above: Komoran Captain and Officers, Dhurringile – POWs of Australia.

If you are interested in where the Komoran crew were interned please go to Tatura WW2 Camps

‘WORLD WAR 2 CAMPS

The Tatura group of 7 internment camps were established in this area because of the distance from a sea port and availability of adequate food and water. Holding between 4 and 8,000 people at any one time, these camps were located at Tatura (camps 1 and 2), Rushworth (camps 3 and 4), Dhurringile Mansion, Murchison (camp 13) and Graytown (camp 6).’

Newspapers across Australia reported stories of the Komoran Crew. Below are just a few copies of these many reports, below chosen for easier reading and quality of print.

Please read the WA Museum story of Komoran

Below: SS Mareeba

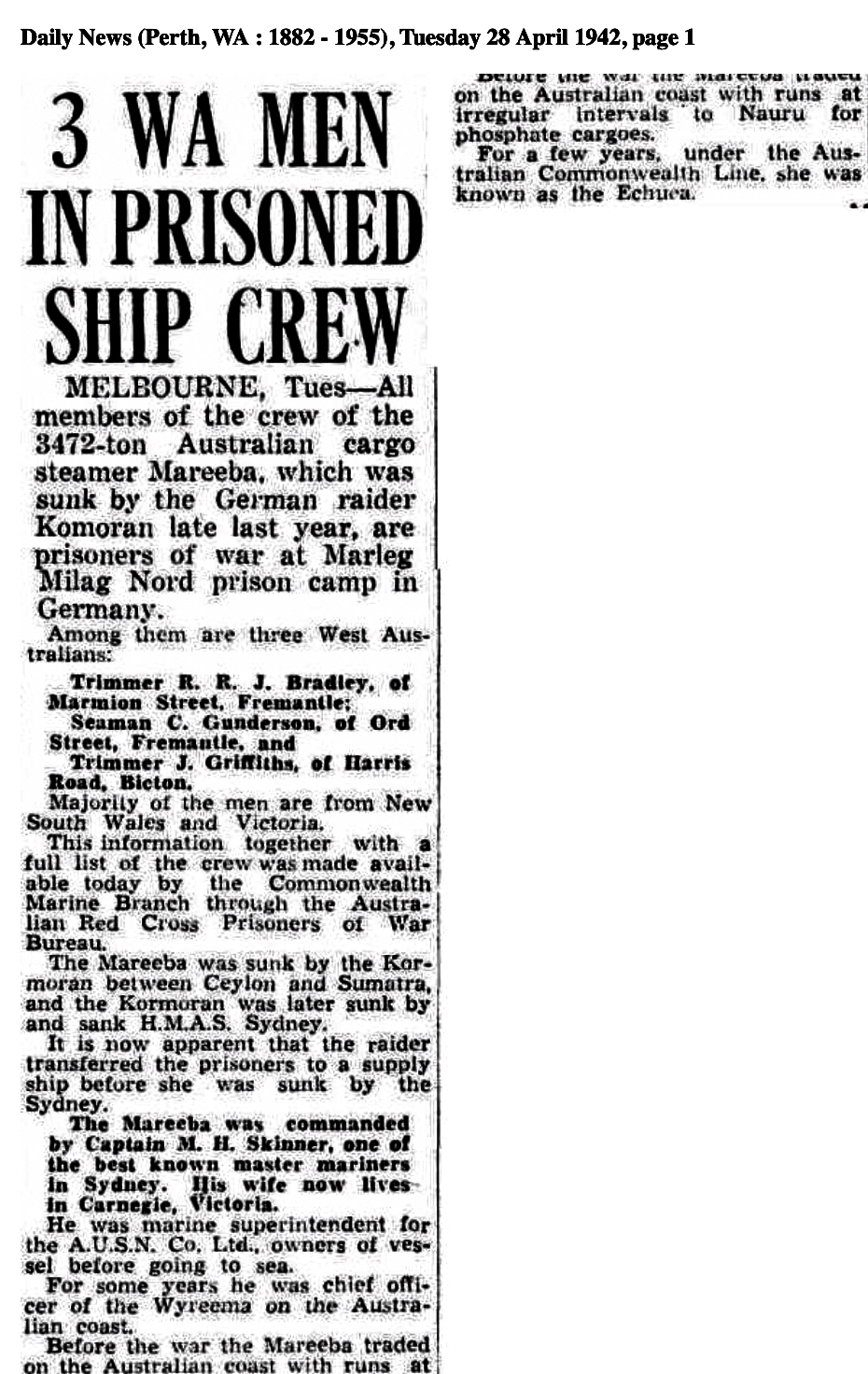

AUSTRALIAN MERCHANT SHIP SS ‘MAREEBA’

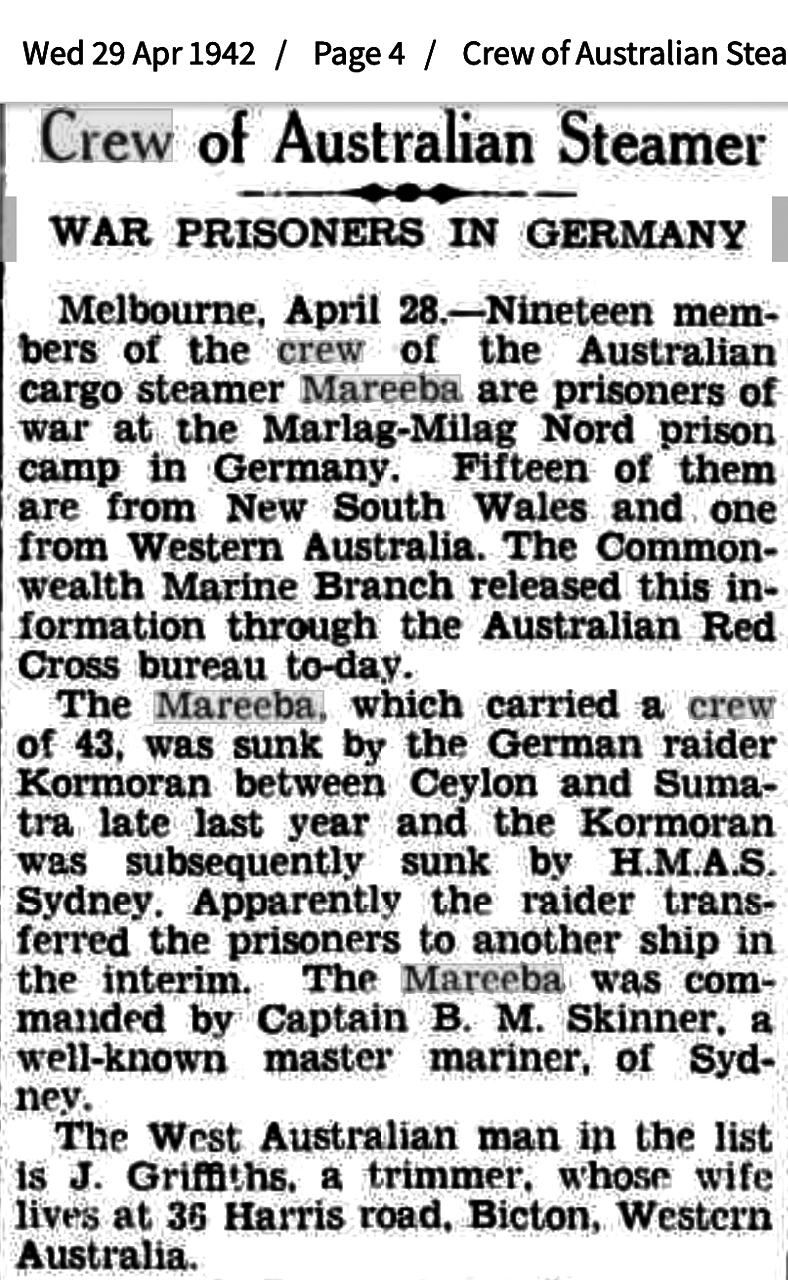

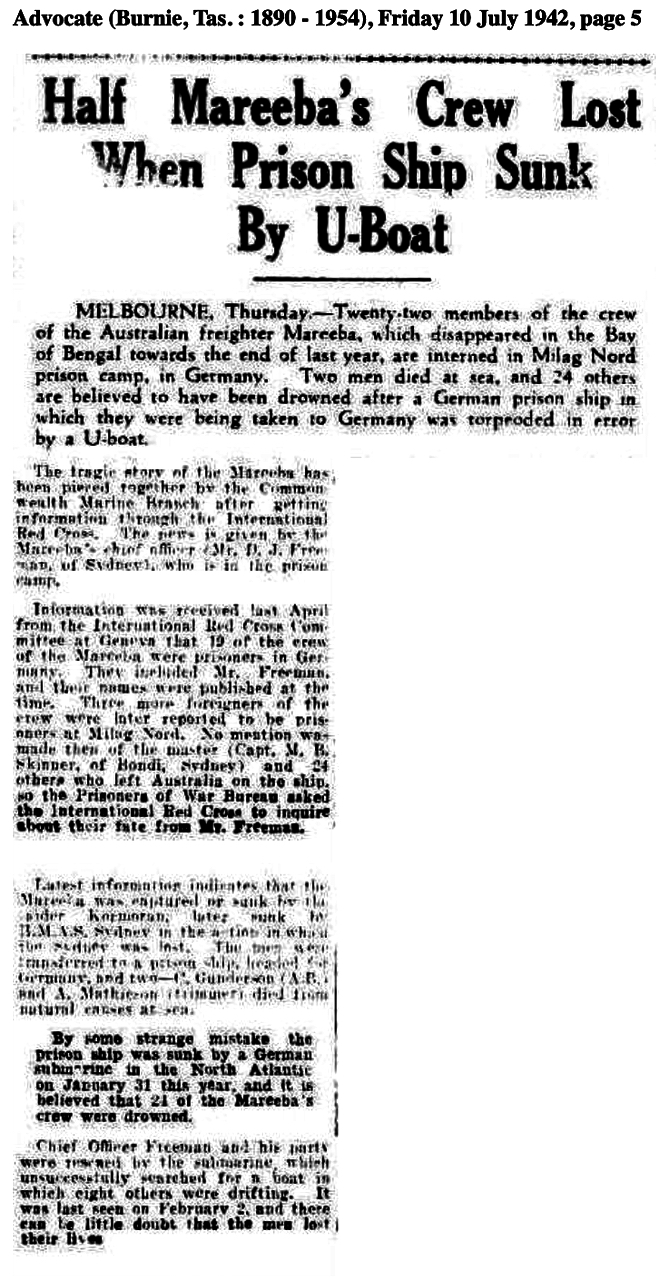

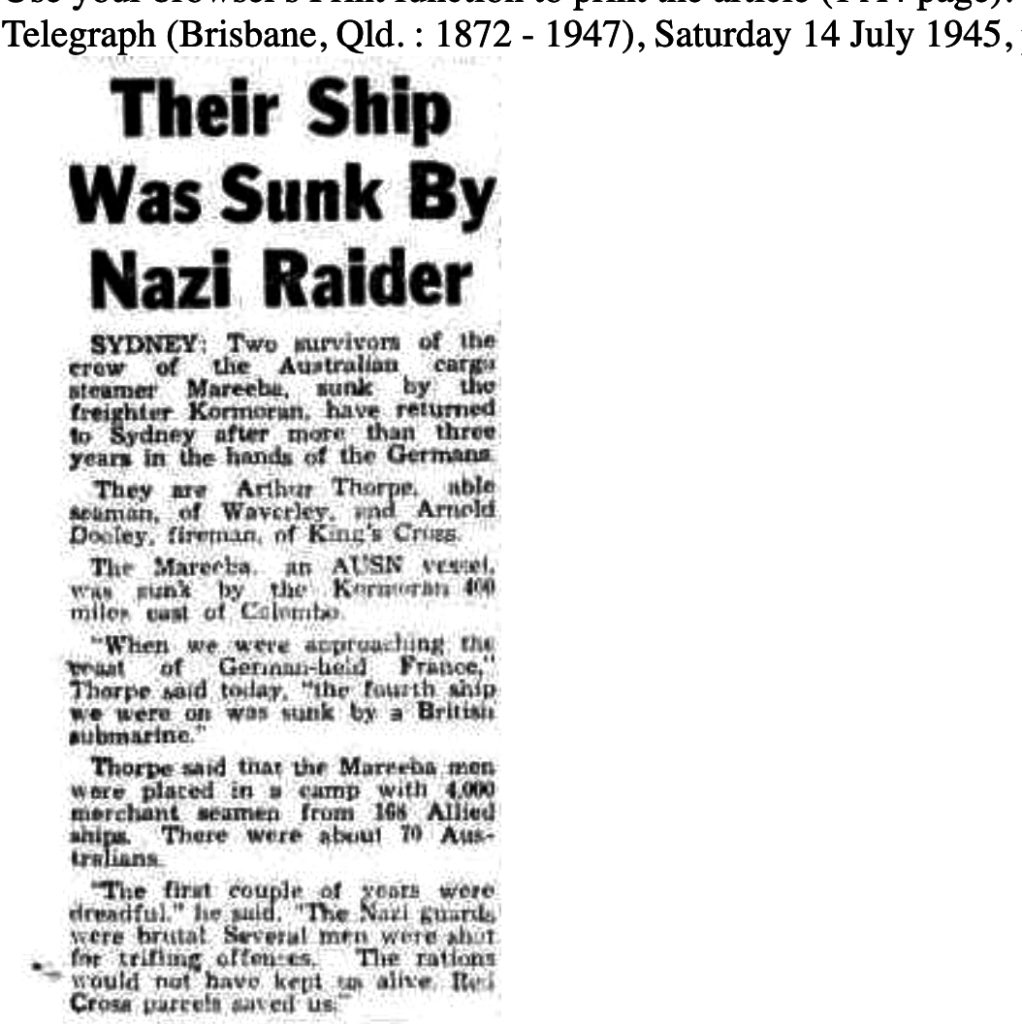

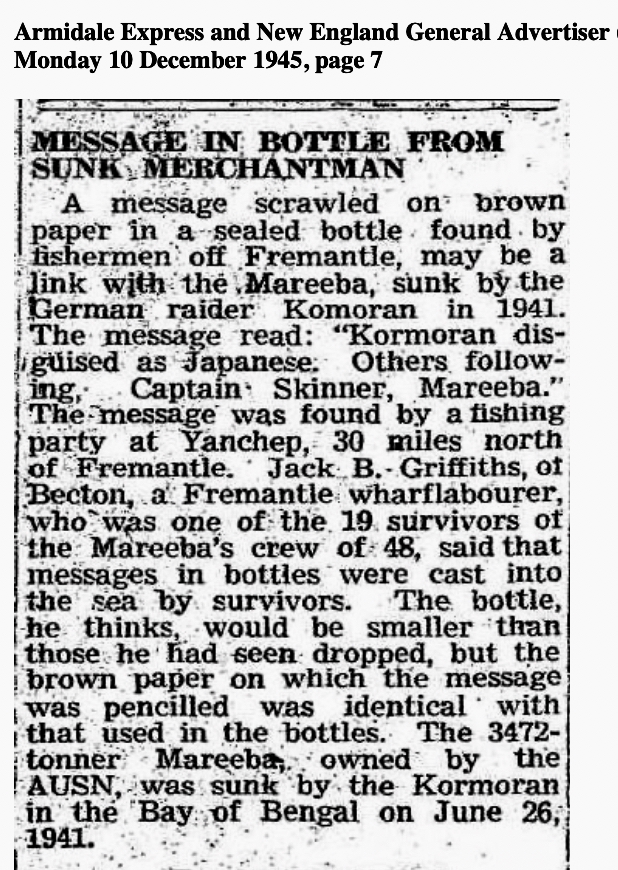

Komoran had in June 1941 attacked Australian merchant ship SS ‘Mareeba’ with 48 crew in the Bay of Bengal. The Komoron crew then boarded ‘Mareeba’ removing her crew to Komoran before scuttling ‘Mareeba’ You can read further details

SS ‘Mareeba’ was built 1921 in Australia, named after the Queensland town. She was carrying 5000 tons of sugar from Batavia to Colombia. She received 9 shots to her hull, several of which hit the engine room. ‘Mareeba’ had received distress signals from Yugoslav ship SS ‘Velebit’ but instead of immediately stopping she made a run for it radioing her position

She was slowing sinking when several crew from Komoran boarded ‘Mareeba’ to place demolition to sink her quickly. All 48 crew of ‘Mareeba’ were captured and spirited away on the Komoran which travelled at top speed through the night and most of the following day to avoid retaliation for the sinking.

The ‘Mareeba’ was one of 8 ships attacked and sunk by Kormoran.

Below: From Kalgoorlie Miner.