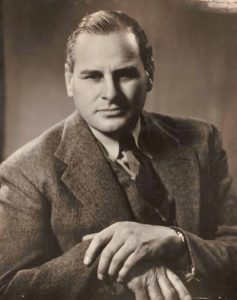

Field Marshal Sir Thomas Albert Blamey, GBE, KCB, CMG, DSO, ED was an Australian general of the First and Second World Wars, and the only Australian to attain the rank of field marshal. Blamey joined the Australian Army as a regular soldier in 1906, and attended the Staff College at Quetta.

What was the leader of WW2 Australian Soldiers really like?

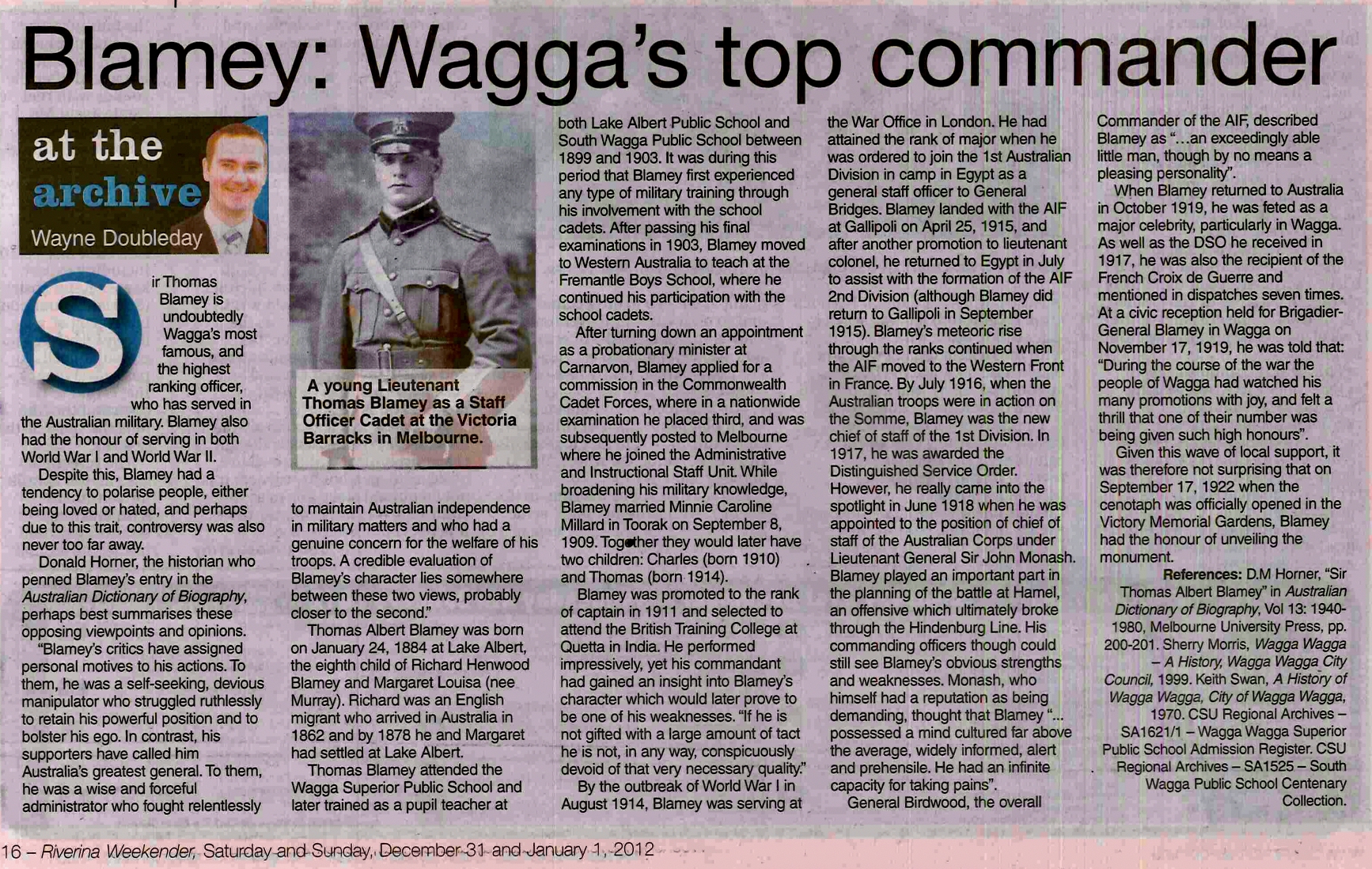

Blamey was certainly a controversial

Australian Miltary Leader

We acknowledge and thank the AWM for the following information:

Thomas Blamey, born near Wagga Wagga on 24 January 1884, became the first Australian army officer to reach the rank of field marshal. Originally a teacher, Blamey received a commission in the Commonwealth Cadet Forces in 1906 and was posted to Melbourne.

In 1910 he transferred to the Australian Military Forces and was promoted to captain. He graduated from the Staff College at Quetta in India in 1913, was in England when the First World War began and joined the general staff of the 1st Australian Division in Egypt. Blamey landed at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915; in July he was promoted to temporary lieutenant colonel and returned to Egypt to help form the 2nd Australian Division.

On the Western Front, Blamey was appointed Chief of Staff and served as General Staff Officer 1 in the 1st Division until June 1918 when he was promoted to temporary brigadier and became Chief of Staff of the Australian Corps. After the war Blamey received several important postings, including one to London as Colonel, General Staff and Australia’s representative on the Imperial General Staff. In 1925, he was appointed Second Chief of the Australian General Staff. Shortly afterwards, however, he left the regular army to become Victoria’s commissioner of police and transferred to the militia.

Considered confrontational, violent, and ruthless, Blamey’s tenure with the police was dogged by controversy; he was forced to resign in 1936 having lied to protect one of his senior officers. He remarried in April 1939 after the death of his first wife four years earlier. Within a month of the Second World War beginning he was given command of the 6th Division. The following year he became commander of the Australian Corps. Despite a mixed performance early in the war – his fitness for command was questioned by some subordinates – Blamey received further promotions and in December 1941 reached the rank of General.

In March 1942, with Japan having entered the war, Blamey returned to Melbourne as Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Military Forces and, under General Douglas MacArthur, became commander of Allied land forces in the Pacific. Overshadowed by the American – MacArthur had the prime minister’s ear – and resented by many senior Australian officers, Blamey encountered numerous difficulties. His removal of several senior officers in Papua under pressure from MacArthur remains controversial.

Blamey conducted a series of successful offensives in New Guinea in 1943 but was criticised late in the war when Australians were involved in operations against long-bypassed Japanese units in New Guinea and Borneo. On a personal level, Blamey’s public drinking and womanising harmed his reputation. Professionally, his failure to stand up for his subordinates prompted one historian to write that he was “the foremost Australian General of World War II but he will never be remembered as the greatest.”

Blamey retired to Melbourne after the war and was promoted to field marshal on 8 June 1950. He died on 27 May 1951.

The Blamey – MacArthur relationship

Below: Blamey, MacArthur and Curtin

Wartime Alliances always have challenges. Alliances and Leadership are fraught with many personalities and little diplomacy or sometimes too much.

Blamey at 5’6 1/2 ” tall was seven years younger than MacArthur. A man of short stature he was was somewhat rotund. MacArthur stood 6ft tall arriving in Australia from Philippines having been evacuated by President Roosevelt as the Japanese took control of the Islands.

MacArthur no doubt, wanted to avenge the humiliation he felt. He wanted total control of the battle for the Philippines and wanted only US forces to undertake the task. MacArthur wanted to return to the Philippines a Hero. It appeared he had learnt very little from the Philippines debacle. MacArthur was specifically directed to include on his staff senior Australian military officers. He selected only US troops to command – his mistake as they had little or no combat experience. He overlooked the Australian Generals and officers who did have combat experience.

With his sole intent focused on the Philippines, MacArthur the Supreme Commander of Allied Forces, left the northern door to Australia, ajar. ‘His directive was to prevent any Japanese landing on the north-east coast of Australia or on the south coast of the island of New Guinea. Although the directive appeared to recognise the strategic importance of Port Moresby and the vulnerability of northern Australia to increased aerial bombardment and invasion if it were to be captured by the Japanese, MacArthur and Blamey took no immediate steps to fortify Port Moresby or reinforce with battle-toughened AIF troops the poorly armed and inadequately trained militia garrisons in New Guinea. This inexcusable neglect of the defence of Port Moresby by MacArthur and Blamey becomes even more difficult to understand in the light of evidence that the Japanese and the Commander-in-Chief of the United States Pacific Fleet, Admiral Chester Nimitz, were well aware of the strategic importance of Port Moresby.’

MacArthur was critical of Australian troops at Kokoda and New Guinea, suggested Curtin send Blamey in person to sort it all out. Curtin did ask Blamey who in turn sacked several senior staff. The Australians were not happy. Was this move necessary?

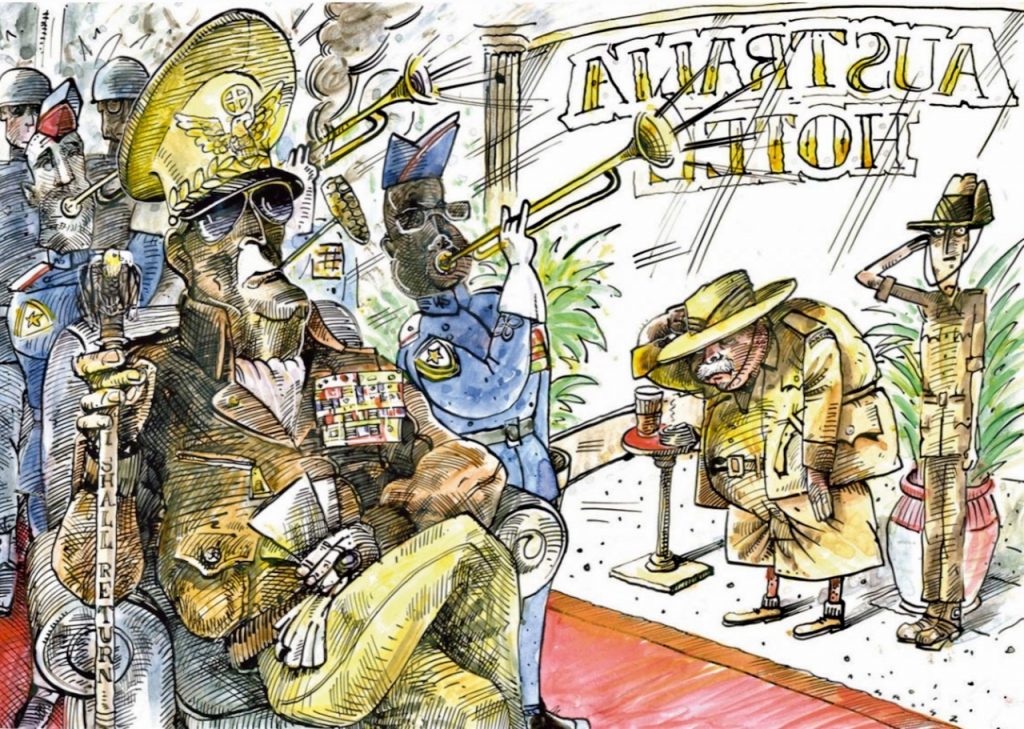

Blamey no doubt hoped for a balanced and positive working relationship with MacArthur and the US. This never happened. MacArthur was like a Hollywood star, dressed sleekly, dressed with braids, usually in his sun glasses. His entrances tended to be grand.

‘Blamey had a sharp mind for the strategic overview, fascistic tendencies and a reputation for favouritism, womanising and drunkenness. He’d never led troops in combat, and his most famous victories had been against the bolshie jobless during his tenure as Victoria’s police commissioner.’

Blamey and his staff officers were sidelined and the achievements of Australian troops deliberately downplayed.

At the surrender of Japan ceremony – MacArthur was the star. Blamey did not feature in proceedings although he was present.

Above: MacArthur, Blamey and Major General Allen, Commander, Australia’s 7th Division in New Guinea.

Above: 2nd from Left MacArthur with Blamey centre. Perfect material for cartoonists! (Blamey really does look a sight in his Bombay Bloomers.)

The following is from AWM it is a review of David Horner’s ‘Blamey: The Commander-in-Chief’ Printed by Allen & Unwin, Sydney 1998.

Many of the points mentioned above are confirmed here.