THE STORY OF B-29 SUPERFORTRESS

BOMBING RAIDS OVER JAPAN

DURING 1944 & 1945

Did you know?……………

The combined atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki inflicted less damage than the great Tokyo firebomb raid of 10 March 1945

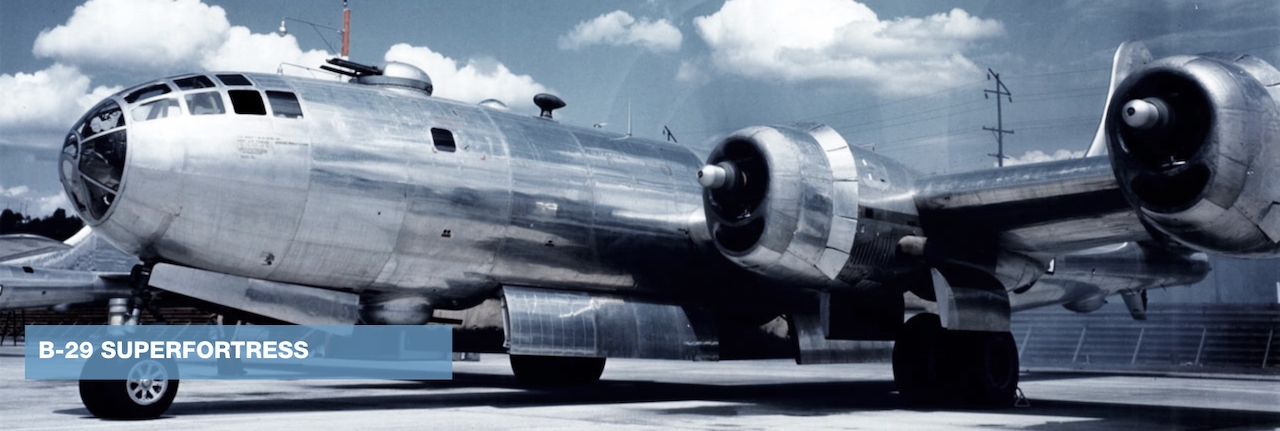

THE FOUR ENGINED SUPERFORTESS WAS ONE OF THE LARGEST PLANES USED IN WW2. POWERFUL AND VERY ADVANCED IN DESIGN.

Operation Meetinghouse is considered the single most destructive bombing raid in human history

POWs in Japanese camps who had food/medicines/clothing delivered to their camps by parachutes during the weeks between war’s end and their eventual departure, happily described how they could see the faces of the B-29 crews as they flew over – that is how low the B-29’s flew and POWs would watch the bomber’s crew ‘wave his wings’ as he departed.

The same B-29s had also earlier flown bombing raids over Japan unaware of the large numbers of POW camps throughout Japapn. Terrified POWs were forbidden to use shelters, searched for safety. Many had been killed working at wharves, factories and indeed their accommodation.

WX4927 CLIMIE, Austin Newman ‘Ossie 2/4th’s Climie was sadly killed during an Allied air raid over Kawasaki Camp 14D on 13 July 1945 – just one month short of the end of the war. He was 37 years old. Read further about Climie.

The Boeing B-29 was designed in 1940 as an eventual replacement for the B-17s and B-24s. The first one built made its maiden flight on 21st September 1942.

Specifications:

| First flight | Sept. 21, 1942 |

| Model number | 345 |

| Classification | Bomber |

| Span | 141 feet 3 inches |

| Length | 99 feet |

| Gross weight | 105,000 pounds (140,000 pounds postwar) |

| Top speed | 365 mph |

| Cruising speed | 220 mph |

| Range | 5,830 miles |

| Ceiling | 31,850 feet |

| Power | Four 2,200-horsepower Wright Duplex Cyclone engines |

| Accommodation | 10 crew |

| Armament | 12 .50-caliber machine guns, 1 20 mm cannon, 20,000-pound bomb load |

Between 1943 and 1946, Boeing manufactured 3,970 B-29 heavy bombers.

The first Superfortess flight over Japan took place on 1 November 1944, when a reconnaissance aircraft photographed industrial facilities.

Following several practise runs in the Pacific the first real air raid codenamed San Ontonio took place during night of 24 Nov 1944. 111 B-29s flew over Musashino aircraft factory on the outskirts of Tokyo. 24 of the planes hit their target with the rest attacking surrounding locations. Only one plane was lost. The American planes were too fast and too high for the Japanese to put up significant defence.

On 29 Nov 1944 the first US B-29 Bombers known as Superfortresses left the US Air Bases at Mariana Islands to fly their first bombing raids over Japan. The US forces had captured Mariana Islands between June and Nov 1944 and immediately began the construction of six airfields.

Below: Trinian, Mariana Islands

Above: Tinian Airfield

Below: Guam Airstrip

Tokyo was now only a 1500 mile flight away and well within the B29 range.

The initial concept of USAAF was to fly from bases in India, however this required refuelling in China before flying to Japan – then only southern Japanese cities were in range and the project required aviation fuel to be transported to both India and China.

The air force continued a campaign of precision raids against Japan’s war industries and high effective targets. It was soon realised Japan’s high winds (especially those from Siberia) and bad weather limited the effectiveness of these raids especially flying at high altitudes. The air force was losing between 4-5%

At this point the air force changed tactics and it was decided they would firebomb Japanese cities to force Japan’s surrender.

This attack was made against Tokyo on 25 February. A total of 231 B-29s were dispatched, of which 172 arrived over the city. The attack was conducted in daylight, with the bombers flying in formation at high altitudes. It caused extensive damage.

Several small night raids were conducted on the region during December 1944 and January 1945.

The Fire-balling of Tokyo -10 March 1945

The USAAF sought new effective tactics for their B-29s.

The first major raid would be over Tokyo – Japan’s largest city with a population of 6 million people and the heartbeat of Japan. Codenamed ‘Meetinghouse‘ it was scheduled for 10 March 1945 requiring extensive planning and co-ordination, and low level flying at night under ‘Meetinghouse’ Commander Brigadier General Thomas S. Power, stationed at Guam.

In preparation for firebombing raid the USAAF tested the effectiveness of incendiary bombs. M69 incendiaries were particularly effective at starting uncontrollable fires. Dropped from B-29s in clusters they used napalm as their incendiary filler.

On 3 January,1945 97 Superfortresses were dispatched on a fire-bombing raid against Nagoya. This attack started some fires, which were soon brought under control by Japanese firefighters. The success in countering the raid led the Japanese to become over-confident about their ability to protect cities against incendiary raids.

The next firebombing raid was directed against Kobe on 4 February, and bombs dropped from 69 B-29s started fires which destroyed or damaged 1,039 buildings. Please read further about the Kobe bombings

On the 10th March 334 B-29 bombers from 12 bombardment groups flew out of airfields located on Tinian, Saipan and Guam. Guam was the furtherest from Tokyo. This was really the first time they would fly low level and at night.

It took two hours and 45 minutes for the Superfortresses to take off, one to three minutes apart, from six runways on Guam, Tinian, and Saipan.

Turbulence was encountered on the flight to Japan, but the weather over Tokyo was good. There was little cloud cover, and visibility from the bombers was 10 miles (16 km). Conditions on the ground were cold and windy, with the city experiencing gusts of between 45 and 67 miles per hour blowing from the south-east.

Almost everyone on Guam, Saipan, and Tinian had seen one crash. If you lost an engine past the halfway mark of the take-off run, you probably would not be able to stop before the end of the runway, and the plane would crash off the cliff or go into the water and explode. Runways were not long. There was little room for error – especially at night.

Before dusk, the pathfinders were in the air while crew members of the remainder of the attack force of 334 B- 29s on three islands were climbing aboard their planes. Because Guam was farther from Japan, its B-29s were already taxiing out.

There was no formation. Each aircraft was on its own, its airplane commander entrusted with the souls on board, its navigator and his special skills never more important than now. The pathfinders were way out in front with most of the bomb groups from Guam coming next, having taken off early enough to overtake the Superfortresses from Tinian and Saipan

At around midnight on 9 March a small number of B-29s were detected near Katsuura, but were thought to be conducting routine reconnaissance flights. Subsequent sightings of B-29s flying at low levels were not taken seriously, and the Japanese radar stations focused on searching for American aircraft operating at their usual high altitudes. The first alarm that a raid was in progress was issued at 12:15 am, just after the B-29s began dropping bombs on Tokyo.

Tokyo’s defenders were expecting an attack, but did not detect the American force until it arrived over the city.

Tokyo had only a token fire department and almost no civil defence infrastructure. It was a city of fragile houses with sliding shoji screens, floored wooden roka or passageways, and fusuma, or partitions of wood and paper.

The first B-29s over sleeping Tokyo were the pathfinders under the leadership of Commander Power. Coming in over the target from opposite directions, the pathfinders dropped their payload, which immediately burst into flames. The target now brightly illuminated in the shape of an enormous fiery “X” and the Pathfinders job completed.

279 B-29s arrived over the target and during two hours and forty minutes of bombing razed the central area of Tokyo.

The B-29s dumped over 1,665 tons of incendiary bombs on Tokyo that night. The napalm inside of the bombs devoured everything they touched. Each of the 279 B-29s bomb loads covered an area around 2,000 feet long by 300 feet wide.

Commander Power’s B-29 circled Tokyo for 90 minutes with a team of cartographers who were assigned to him mapping the spread of the fires.

Visibility over Tokyo decreased over the course of the raid due to the extensive smoke over the city. This led some American aircraft to bomb parts of Tokyo well outside the target area. The heat from the fires also resulted in the final waves of aircraft experiencing heavy turbulence. Some American airmen also needed to use oxygen masks when the odour of burning flesh entered their aircraft.

19 Superfortresses unable to reach Tokyo struck targets of opportunity or targets of last resort, some crashed into nearby mountains. Some aircraft turned back early due to mechanical problems or pilots deciding to abort the fight due to anxiety about their prospects of surviving the mission.

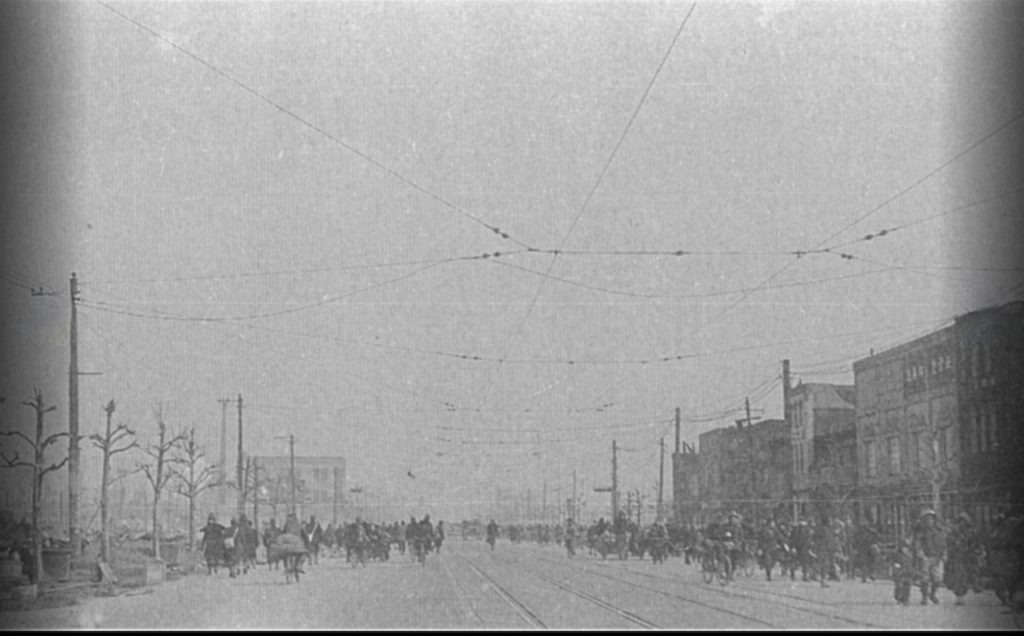

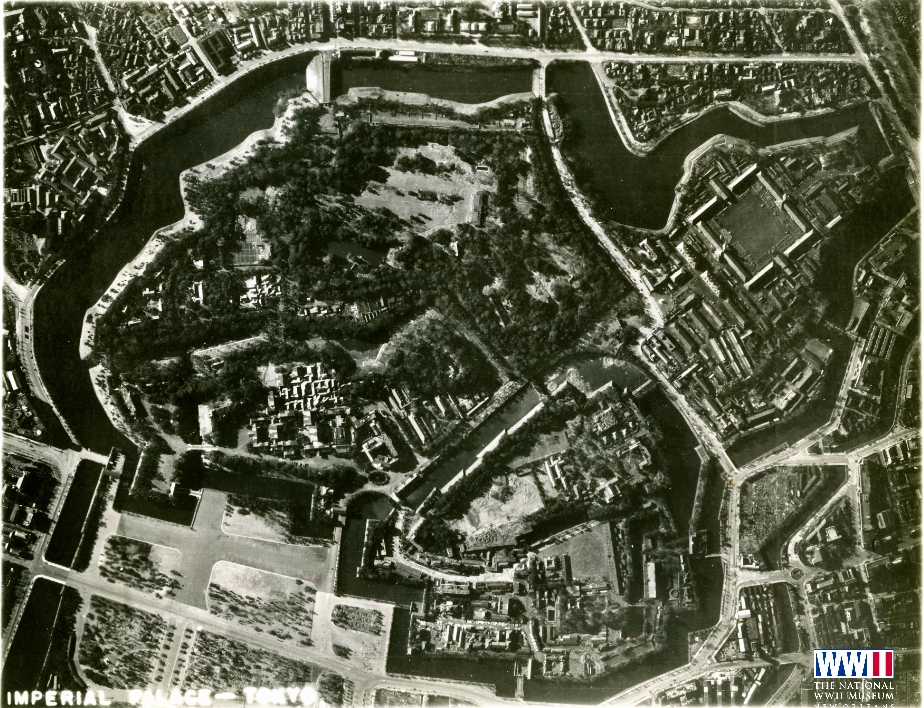

Above: Tokyo 1945 before the Bombing Raids. Below: The Imperial Palace 1945. The Bombing Raids were ordered the Imperial Palace to be safeguarded at all costs.

We wish to thank and acknowledge ‘The Digital Collections of The National WWII Museum’. New Orleans, USA

OROTE POINT, GUAM. 1945. OROTE AIRFIELD’S RUNWAY IS SURROUNDED BY A CITY OF STRICTLY FUNTIONAL QUONSET HUTS, WORKSHOPS, TENTS AND STORES DUMPS. THERE ARE OVER 200 AIRCRAFT IN THE PHOTOGRAPH AND THEY INCLUDE MOST TYPES WITH WHICH THE US NAVY FOUGHT THE PACIFIC WAR, RECENTLY CONCLUDED. (NAVAL HISTORICAL COLLECTION)

As the bombers passed over the target area and opened their bomb bay doors to unleash their payload, many of the crews were met with a sickening odour. An odour they returned to their bases with.

“the bomb bay doors opened, the plane filled with smoke from the ground and we smelled this horrible odour. We closed the bomb bay doors after we dropped and headed to sea. The odour was still so strong in the plane that the pilot ordered me to open the doors again to let the fresh air in. You could only imagine what was going on down below us.”

The odour was the smell of burning human flesh.

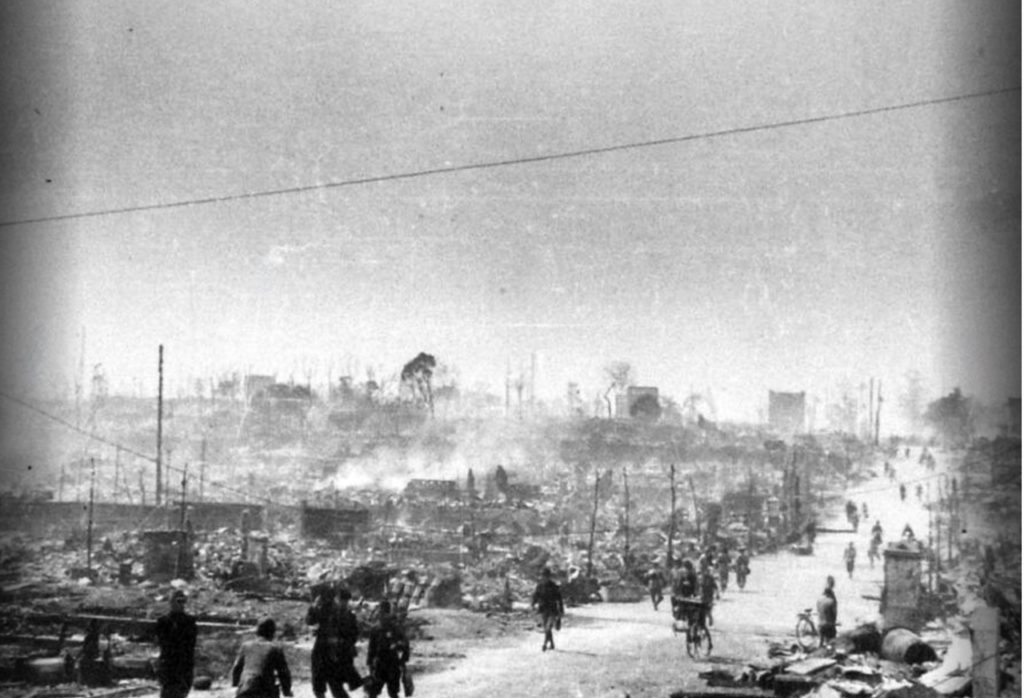

Flying at low altitude they dropped 1,665 tons of incendiary bombs on Tokyo. The resulting fire destroyed 16 sq miles of the city representing 8% of its urban area. 83,000 people were killed another 40,000 were injured. Over 1 million people lost their homes and war production was clearly hurt. The most destructive single air attack in history.

While Japan’s defences didn’t pose too much of a threat to the B-29s the B-29’s own bombs, which created destruction and firestorm did. The firestorm, with its intense heat and winds, created tornadic activity that caused updrafts in the flames creating massive turbulence. The turbulence was such that the bombers buffeted along with sudden altitude changes as much as 1,000 feet, up or down. In some cases, the winds actually flipped some of the B-29s over in mid-air. Their crews only realized they were inverted when everything inside the airplane came crashing down on them, and the flames that were below them an instant before were now above them.

American casualties were significantly less. Around 90 airmen were missing after the raid, and 14 B-29s never returned either due to enemy fire or accident.

The sheer destruction and violence of the raids achieved their goal.

There would be no amphibian invasion of Japan.

Morale among the citizens of Tokyo, who were already short of food, plummeted. For the first time, many came to the realization that the war was lost.

The weather that night was a quarter-moon. Most B-29s were making a key turn at Choshi Point, east of Tokyo, the IP, or initial point, where they would turn west to begin their planned run-in. Crew members squeezed into their flak vests, heavy and cumbersome garments with steel plates that could absorb shrapnel. Some donned helmets that interfered with earphones but promised head protection. None saw any night fighters. Antiaircraft gunfire would be a formidable adversary, but the fighters were somehow missing.

An intelligence summary credited the Tokyo region with 500 antiaircraft guns, “as many guns as ever protected the German capital of Berlin.” Bomber crew members feared these guns, yet they were never as effective as their German counterparts.

Japanese cities had been equipped with air-raid sirens, blackout facilities, and underground shelters for almost 20 years, yet people at home and on the street often ignored them. In Tokyo, shelter construction, especially in the area near the bay, was complicated because they could not be dug more than a few feet without encountering ground water. Many people simply stayed where they were when the bombers approached. Perhaps inured by the apparent inability of the Americans to hit anything with their bombs, urban residents dismissed the appearance of the B-29s on the night.

A strong wind had prevailed the previous day – rattling the panes in doors and windows all over the city, the same wind the Americans hoped would spread the fire they were bringing, and most people had gone about their day routinely. For the past few nights single B-29s had appeared over the city, not dropping any bombs but flying very low and setting off the searchlights and antiaircraft fire. This was reconnaissance and it made many in the capital uneasy, yet routine activities continued, and after dark the

The sirens were silent and the lights were off when the B-29s arrived. Most in Tokyo were sleeping.

Also awaiting the arrival of the B-29s were Japan’s fragmented air defence network and Tokyo’s nearly dysfunctional civil defence system.

Airfields were scattered all over the Tokyo region, but the job of defending the capital belonged to the Japanese Army’s 10th Flying Division, with 210 fighters. Tonight, as it would turn out, the low-level B-29 approach took the fighter force by surprise. In the early minutes of Saturday, March 10, 1945, they were receiving little direction from ground controllers, and their flights were not coordinated with searchlight and antiaircraft batteries. Fighters prowled the Japanese coast, but their pilots had no guidance from ground radar stations and never came within eyesight of a B-29.

The Army was responsible for antiaircraft gun batteries in and around Tokyo.

Ordinary people had no defence against a confetti of exploding M69s. In Tokyo, the authorities had sought to equip each household with a grappling hook, a shovel, a sand bucket, and a water barrel. They were useless.

Tokyo’s fire department was pitiful. In recent months, its strength had increased from 2,000 to 8,100 firefighters. The fire department of New York, which no longer faced any likelihood of being bombed from the air, was made up of almost 10,000 firemen. In 1943, the Tokyo department had 280 pieces of fire apparatus. In early 1945 it had 1,117 pieces. A shortage of mechanics idled more than half of them.

Heat and Horror

It began just after 11 pm Tokyo time, or midnight according to the Chamorro (Guam) time by which the Americans set their watches. Sirens sounded.

The main force of B-29s—400 miles long—spent 2 1/2 hours passing over Tokyo.

They unleashed a fire that was more severe than the conflagrations that razed Moscow in 1812 and San Francisco in 1901, even the fire that followed Tokyo’s terrible earthquake of 1923. Even taking the subsequent atomic bombings into account, they ignited the hottest fires ever to burn on Earth.

Once the flames came, there was no escape. In 30 minutes, the fires were out of control, quickly overwhelmed Tokyo’s wooden residential structures. The firestorm replaced oxygen with lethal gases, superheated the atmosphere, and caused hurricane-like winds that blew a wall of fire across the city.

Brigadier General Thomas S. Power—Tommy—the overall air commander of the mission, stayed over the target for 90 minutes. Power was making red crosses on a hand-held map to show blocks where fires broke out. He wore his red crayon down. Crew members were becoming nervous. No one liked lingering this long over a well-defended target.

Power was not unmoved by the human suffering beneath his wings. He was one of the last B-29s to depart the target. It was 3:05 am, Chamorro (Guam) Standard Time, March 10, 1945.

The “all clear” sounded at 2:37 am Tokyo time, or 3:37 am on the clock used by the Americans.

Vast warehouse areas, big manufacturing plants, railroad yards, stocks of raw materials, the whole complex of home factories—all of it was gone. The broadcast studio JOAK, from which the voice of Tokyo Rose was sent out to taunt B- 29 crew members, was heavily damaged. The Imperial Hotel, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, needed serious repair. The biggest railroad stations in Asia—Ueno and Tokyo Central— were completely wiped out.

104,000 Tons of Bombs Dropped on Tokyo.

Tokyo lay broken and destroyed.

After 15 hours and four minutes in the air, the great Tokyo firebomb mission’s air commander, Brigadier General Thomas S. Power, landed at Guam’s North Field.

Of 334 bombers launched against Japan in the early evening hours of March 9, 1945, some 279 aircraft arrived over target and passed over the primary aiming point at “Meetinghouse,” the centre of Tokyo.It was 8:30 am, Chamorro (Guam) Standard Time, March 10, 1945.

By the time the guns went silent, B-29s had dropped 104,000 tons of bombs on Japan, reducing to rubble 169 square miles in 66 cities. The bombing missions left homeless 9.2 million civilians, including 3.1 million in Tokyo.

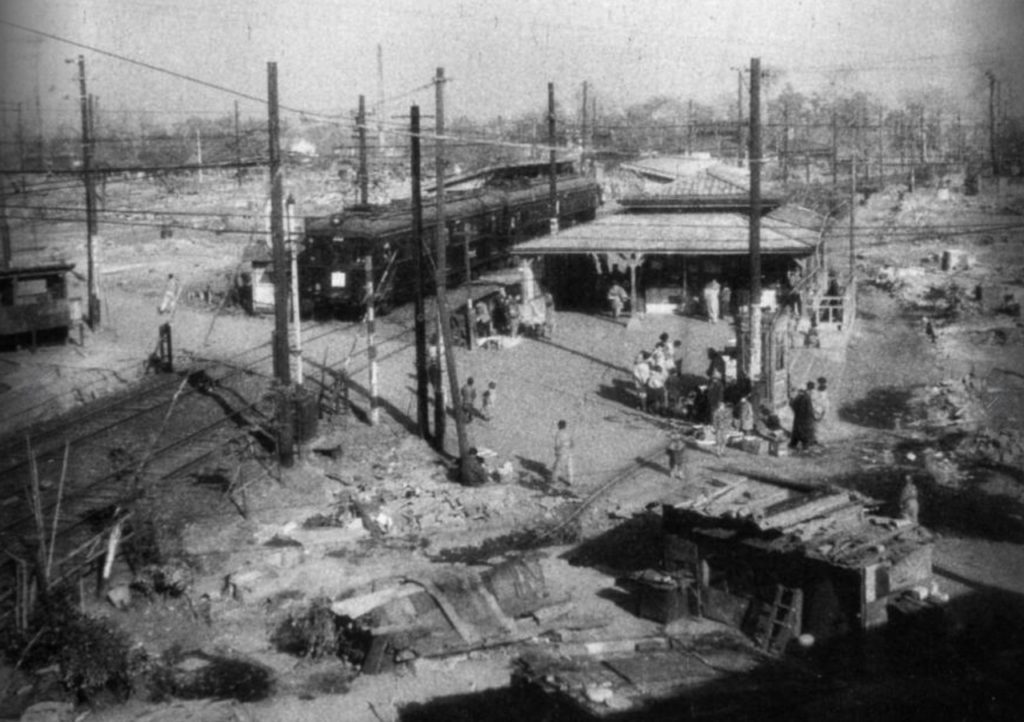

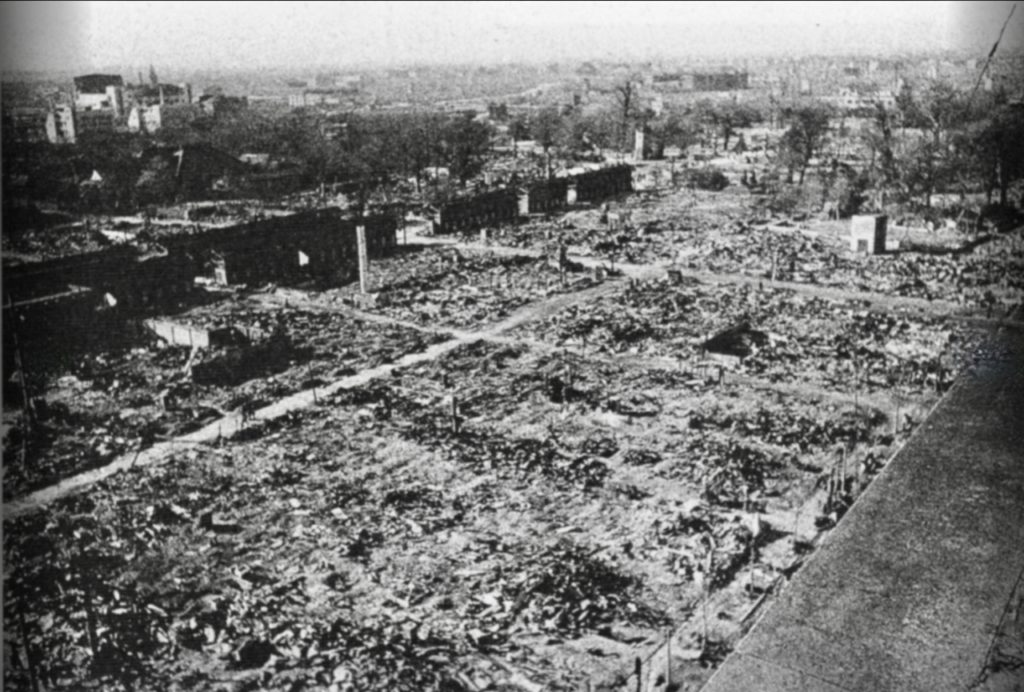

Below: Tokyo, the world’s third largest city, was reduced to rubble by war’s end.

Above: A lone train arrives at a Tokyo Station

Above: Wooden carts carrying away burnt bodies.

Above: Police and soldiers removing bodies.

The fire-bombing of Japan’s cities did not end with March 9-10.

Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe, Nagoya (again) all were attacked with incendiaries in the same week as Tokyo. Incendiary raids would rain down upon Japanese cities all across the country. Altogether, air raids on Japan—incendiary, conventional, and later nuclear—would continue until August 10, 1945.

Please read about the bombing of Kobe

After the success of the first raid it was decided to continue the night-time raids on Japanese cities. The raids continued and all the large cities were attacked and mostly destroyed. Japanese war production was crippled.

While the total number of Japanese killed in the raids is not known, estimates range from 250,000 to 900,000.

A total of 160,800 tons of bombs were dropped on Japan in the less than one year of bombing. A total of 2,600 bomber crew member died either when their planes crashed or in captivity.

Between June 1944 and August 1945, 402 B-29s were lost bombing Japan—147 of them to Japanese flak and fighters and 255 to engine fires and mechanical failures. The combined atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, inflicted less damage than the great Tokyo firebomb raid.

Below: B-29 ‘Enola Gay’ which dropped the first atomic bomb 6 August 1945 on Hiroshima. (now a museum piece)

After the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by nuclear weapons, Japanese Emperor Hirohito finally conceded defeat in August. This was only after hundreds of thousands of his subjects had been killed due to the aerial bombing.

Questions about Hirohito continue to be asked today by so many.

What did Hitrohito know?

Was he the man who made the decisions for Japan’s warfare?

Should he have been charged as a war criminal?

Below: Hirohrito on his favourite horse named Snow White.