War is always a treacherous game!

One’s enemies are not necessarily on the other side.

SINGAPORE WAS A HOTSPOT FOR JEALOUSIES

And after Surrender – Changi was filled with officers with little to do. It was full of jealousies and probably gossip.

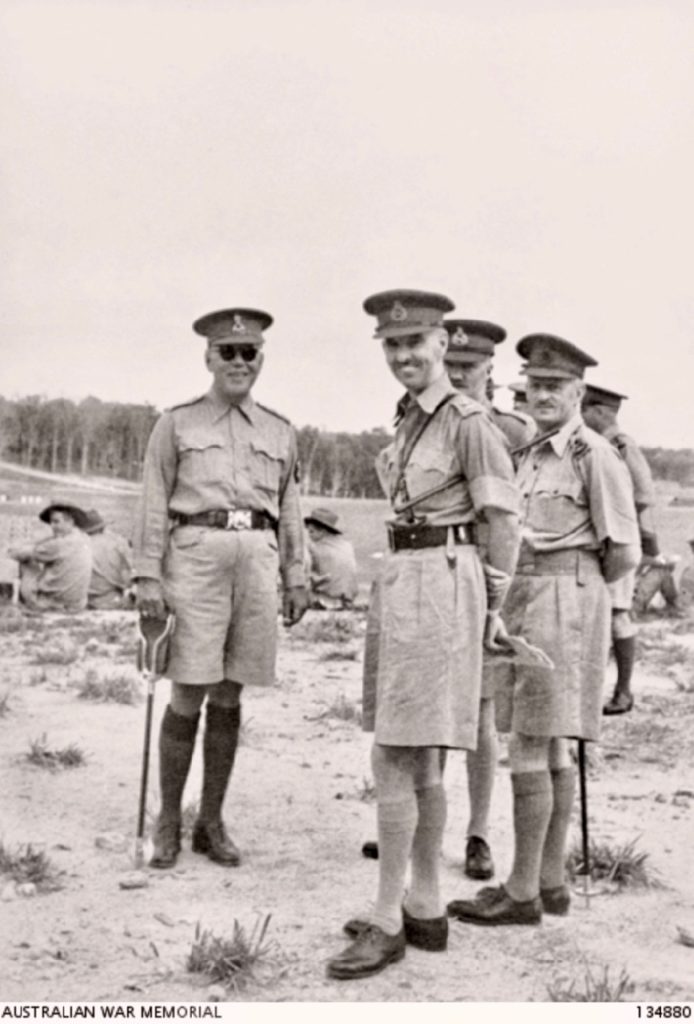

Percival in Centre with Sultan of Johore and Bennett on his right.

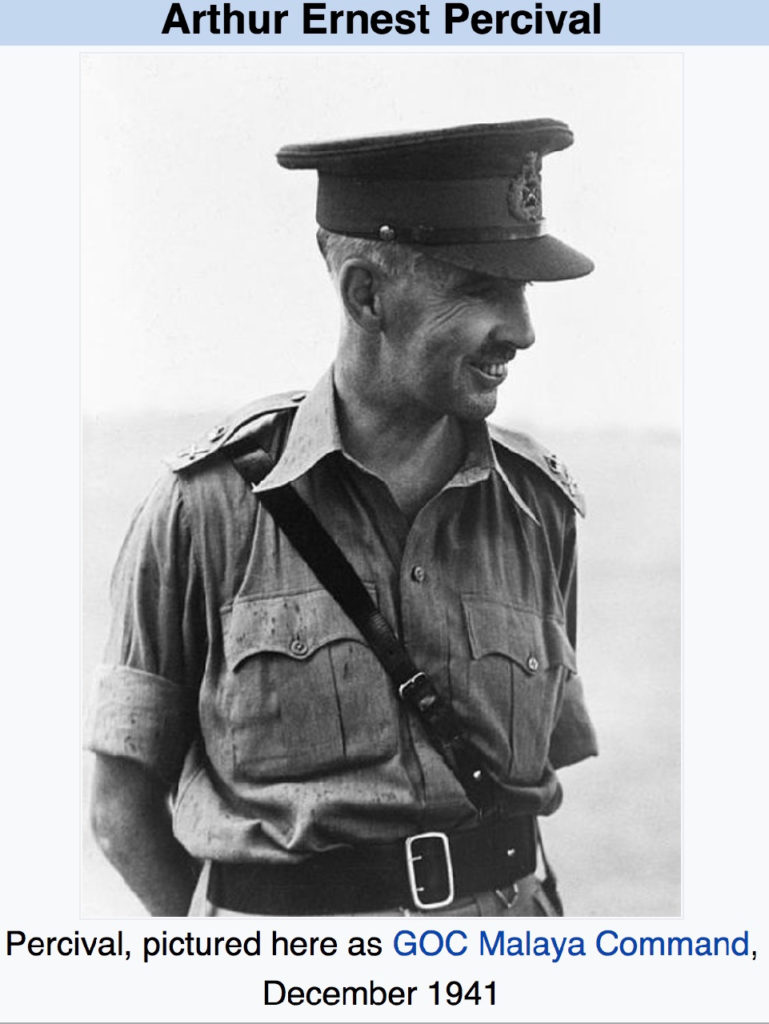

In April 1941, with a promotion to lieutenant-general, Percival was appointed GOC Malaya.

It was common knowledge any man with any strength of character, talent in the British Army in Malaysia/Singapore was soon transferred to the European Front.

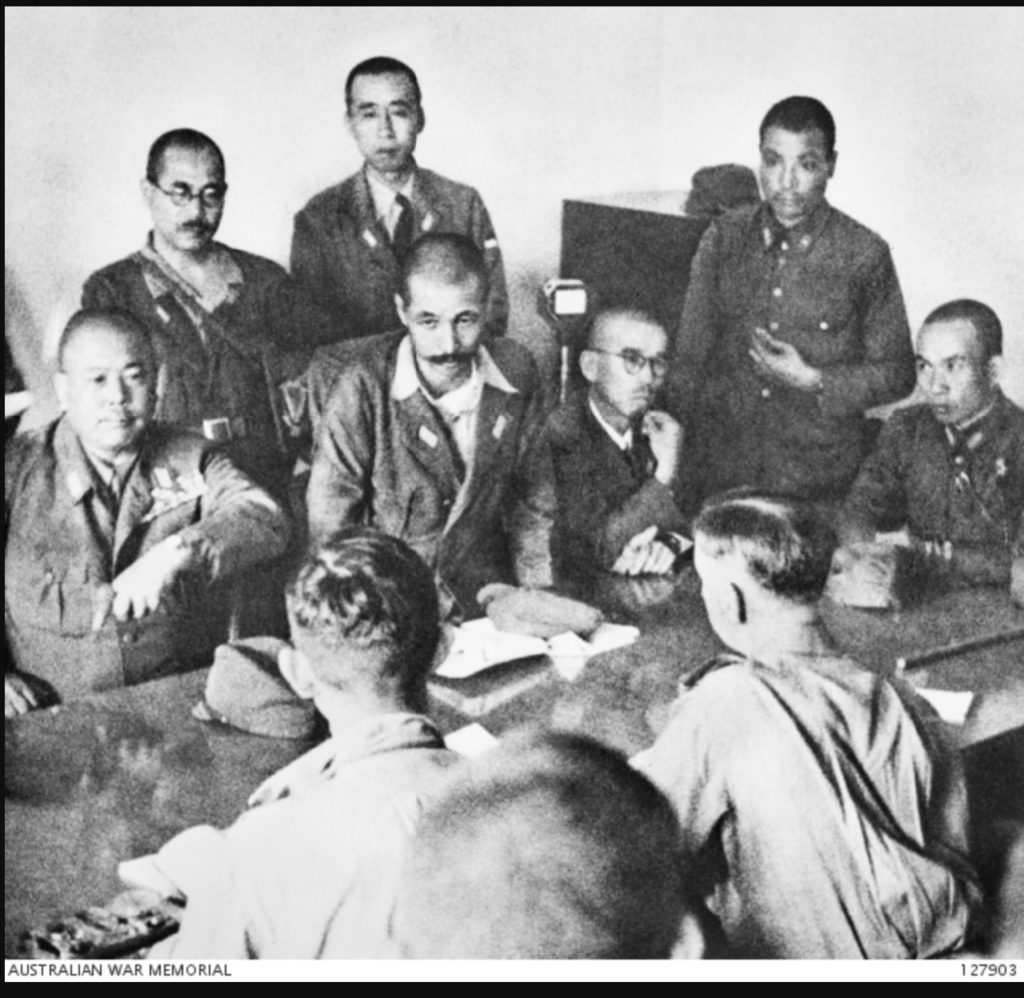

At the Surrender 15 February 1942 at the Ford Factory – Percival is on right.

General Percival is at the centre of Japanese Photographers Feb 1942

General Percival is at the centre of Japanese Photographers Feb 1942

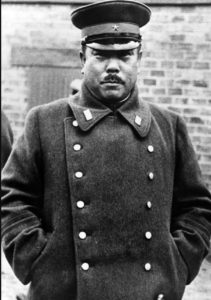

Yamashita – the Japanese General who outfoxed Percival and Malaya Command – surely Wavell should have taken some responsibility for the surrender.

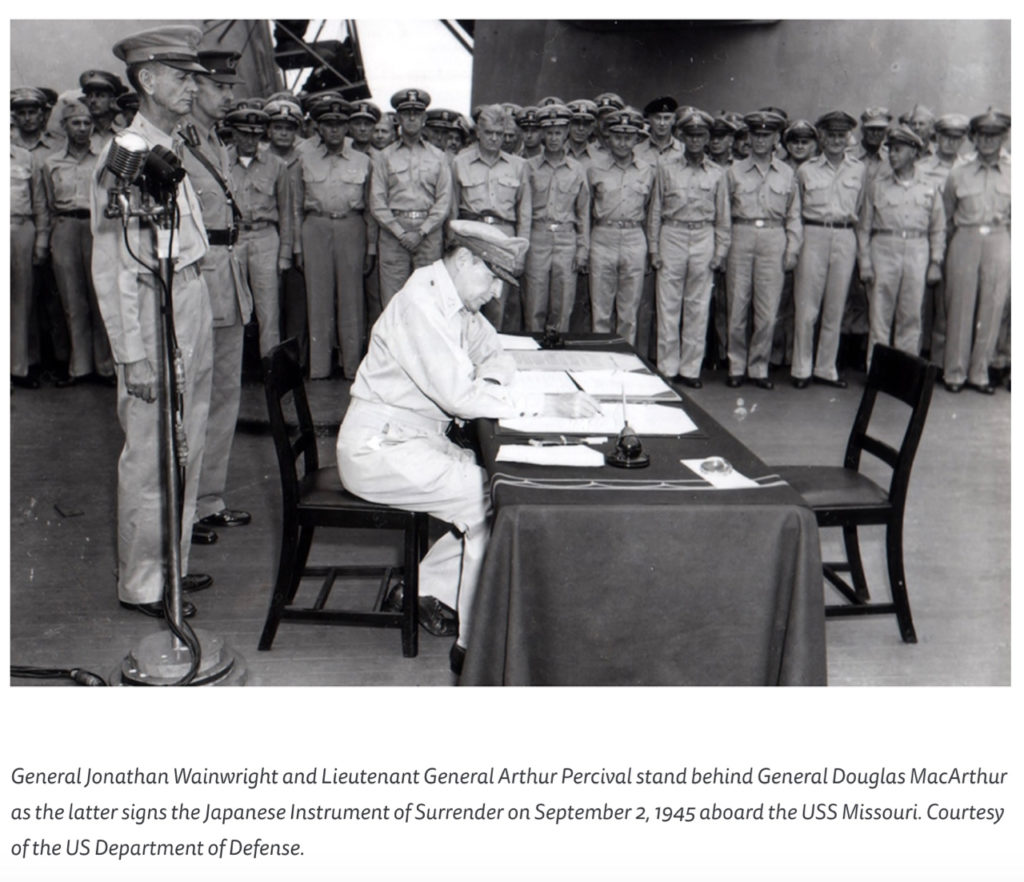

Following the defeat at Singapore on 15 Feb 1942, Percival spent time in Singapore as POW at Changi before being sent to Formosa and then onto Manchuria with several dozen VIP captives. Both he and US General Wainwright were held at a special camp at Hsian in Japanese-occupied Manchuria. Hsian was about 100 miles north east of Mukden.

An OSS team had arrived at Hsian in August 1942 and freed them just weeks previously and before the Russians could reach him – Percival was recovered at the same time.

The Surrender, 2 September 1945

There were more than 250 warships anchored in Tokyo Bay and soon the sky would be filled with 450 carrier planes from US 3rd Fleet flying over in formation followed by US Army Air Force B-29 Bombers.

On VJ-Day, MacArthur invited two unexpected guests to witness the signing.

“Will General Percival and General Wainwright step forward and accompany me while I sign?” General Douglas MacArthur

General MacArthur invited Wainwright and Percival to the signing of Japan’s surrender on board USS ‘Missouri’.

‘General Douglas MacArthur never surrendered the Philippines. He was ordered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to relocate his headquarters to Australia. On the night of March 12, MacArthur, his family and some members of his staff were evacuated by PT-boats from Corregidor to Mindanao. They flew from the Del Monte Airfield to Australia. The US Armies in the Philippines were surrendered by Major General Jonathan M. Wainwright.’

‘Unfortunately, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, December 8, 1941 (Philippine time) was a real surprise for MacArthur’s undermanned, underequipped command. Without any expectation of immediate reinforcements and supplies, it had to fight a rearguard action down the Bataan Peninsula and, finally, Corregidor. Wainwright had to surrender the entire USAFE or IJA General Homma would resume hostilities to the end.’

US General Wainwright had been the man left holding the fort at Corregidor in the Philippines after MacArthur departed the islands. Wainwright surrendered his force in May 1942, and he went into captivity.

‘Before leaving them, MacArthur gave his desperate troops false hope of reinforcements. MacArthur assured them that many thousands of fresh troops were on their way, with strong air support, to relieve the beleaguered American and Philippine forces on Bataan. He ordered them to fight on until these reinforcements arrived. The promise of a relieving force from the United States was a cruel lie, and MacArthur knew it to be so. The order to sick and starving troops to fight on in a hopeless cause.’

From the safety of Australia, MacArthur orders his troops to fight to the end

From the safety of Australia, MacArthur sent the following

callous message to General Wainwright:

“I am utterly opposed under any circumstances or conditions to the ultimate capitulation of this command (i.e. the Philippines). If food fails, you will prepare and execute an attack upon the enemy”.

MacArthur also lied that reinforcements were on their way from US.

One of the abandoned Americans on Bataan, Brigadier General William E. Brougher expressed the views of most of the sick and starving abandoned troops when he described the order and lie as:

“A foul trick of deception played on a large group of Americans by a commander-in-chief and his small staff who are now eating steak and eggs in Australia”.

And then there was Lt General Henry ‘Gordon’ Bennett

Australia’s most controversial Second World War commander.

The man who left his post prior to surrender at Singapore and high-tailed back to Australia.

Even today, Australians have varied views on Bennett’s actions.

The Australian Government and General Blamey were very aware that occasions would arise when an Australian commander’s views would differ from those of the British commander under whom he would be serving. WW1 had shown this to be a realistic problem.

Blamey introduced a charter ‘decalaring Australia was an independent nation whose forces remained under its command even when operating under a British commander.’

This charter was formally recognised by the British Government 26 March 1940.

This charter would be put to the test on a number of occasions during WW2 and was considered a shrewd move by Blamey. He has consulted Generals White and Squires and a Justice of the High Court. Charles Bean, the Official Historian for WW1 had communicated to Prime Minister Menzies about the ‘problems of cooperating with the British.’

On the outbreak of World War II Bennett was junior only to Sir Brudenell White and Glasgow, and was in no doubt that, if an Australian expeditionary force were raised, he would be its commander. He was therefore furious when Major General Sir Thomas Blamey (an ex-regular officer with whom he had clashed) was appointed to head the 6th Division and later the A.I.F. The decision to pass over Bennett was not a matter of revenge on the part of politicians and senior Staff Corps officers, as he and his supporters alleged; his military qualities were generally acknowledged.

Because of his temperament, he was considered unsuitable for a semi-diplomatic command, and one that involved subordination to British generals. Bennett was as scathing of British officers as he was of Australian regulars.

Worse was to come. On the formation of the A.I.F.’s 7th, 8th and 9th divisions, command in each instance went to others. Bennett languished in Eastern Command until August 1940 when White’s sudden death occasioned the appointment of Major General (Sir) Vernon Sturdee as chief of the General Staff. Sturdee nominated Bennett to succeed him as commander of the 8th Division on 24 September. The humiliation of the first year of the war combined with his ambition spurred Bennett to make up lost ground, particularly against Blamey.

In February 1941 Bennett flew to Malaya and established his headquarters. He was to be joined by only two of his brigades, the third being detached for service elsewhere. His relationships with his senior officers were unhappy and some of them attempted at one stage to have him recalled on medical grounds. Bennett’s dislike of regular officers was unabated and was felt within his command, but his most antagonistic relationship was with Brigadier H. B. Taylor, a former C.M.F. officer.

Bennett’s dealings with British senior officers, especially with the General Officer Commanding, Malaya, Lieutenant General A. E. Percival, were similarly devoid of harmony.

The above is from Australian Dictionary of Biography https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bennett-henry-gordon-9489

Australia’s SMO Albert Coates was informed of the news Bennett had escaped Singapore. Bennett had not passed through Tembilahan where Coates was. Coates wrote although there were various comments about Bennett’s actions, he kept his counsel. However Coates was shocked by Bennett’s statement on arriving in Australia, that ‘all the wounded had been evacuated’. This was not true.

_________________

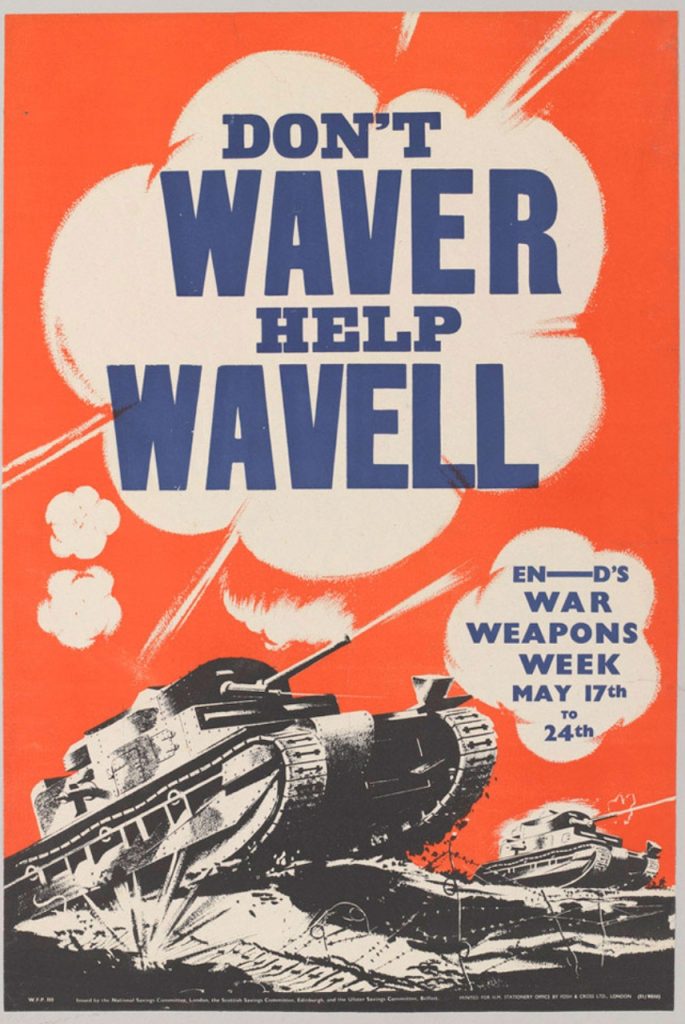

And what of British Lt-General Sir Archibald Wavell, Head of the ABDA (American-British-Dutch-Australian) Command which included Singapore, Malaya, the Dutch East Indies and other regions.

Percival was subordinate to Wavell

Surely Wavell should have taken some responsibility for the Surrender of Singapore?

Wavell would go on to become Viceroy and Governor General of India 1 October 1943 – 21 February 1947 and replaced by Mountbatten.

General Wavell was head of the ABDA (American- British- Dutch- Australian) Command which included Singapore, Malaya the Dutch East Indies and certain other regions. 1 General Percival was thus Wavell’s subordinate.

By the outbreak of WW2 Wavell was GOC-in-C Middle East. Early successes against the Italians turned into costly failures in Greece and Crete and Wavell lost the confidence of Churchill; their temperaments differed completely. Wavell was sent to India as C-in-C. After Pearl Harbor Wavell was made Supreme Allied Commander for the SW Pacific and bore responsibility for the humiliating loss of Singapore (he quickly recognized that it could not be held).

Problems in Burma tested Churchill’s patience and he was removed from command to be Viceroy and Governor General of India. As civil unrest and demands for independence grew, in 1947 Prime Minister Attlee replaced Wavell with Mountbatten who oversaw Partition. Wavell died in 1950, after a life of huge achievement tempered with many reverses, most of which were not of his making.

The Wavell Report made scathing allegations against Australian Soildiers leading up to the Fall of Singapore, given to Churchill and released to the public 50 years later.

These allegations included desertion, indiscipline and failure to send our required patrols.

‘The British-led Allied High Command received a report that about 2,000 Australian soldiers were loose in Singapore. A Staff Captain of the 22nd Australian Brigade was sent to round up these men and return them to their units. However, he could only find a few Australians. But after a check, Australian unit numbers were verified. It was clear at the time, that the original report made to the Allied High Command, was exaggerated. It should be noted that there was no effort on the part of the British to round up its men.’

‘There was evidence that some allied soldiers broke under pressure and ran from the battlefield. Groups of soldiers, including Australians, often drunk, were found roaming the streets and looting. In a few cases, it is reported that unidentified soldiers forced women and children off ships at gunpoint to take their places themselves. Other claims seem to be based more on hearsay and not evidence.’

Australians were the first to fight the invading Japanese. As they were overran, they often had to make their way back through Japanese lines, or if they were lucky, find a boat. Within a few days there were many soldiers unable to make contact with their companies and battalions. They had to make their way to Singapore – one place was the YMCA – where they could find food, drink and maybe grab a few minutes sleep before finding their places once again or regrouped to form new defence lines.

The Australian, Indian and British army was made up of large numbers of new recruits barely trained.

The Australian Official History on the Fall of Singapore, does not provide a detailed account of desertions but only that some Australians deserted during combat.

However, the British Official History provides an interesting comment. It notes that the Australian 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion was the only unit that was at full strength (135 or more of their soldiers were reinforcements with little or no training – ‘E’ Coy and nearly another 100 well trained machine gunners went to Java).

After sustaining many losses while fighting on the Malay Peninsula, the remainder of the 8th Division’s numbers were boosted with untrained reinforcements (they also sailed on Aquitania) In fact, it was observed that in the 2/29th Battalion which had suffered substantial losses, a great number of men had not fired a rifle and about 200 had not been trained to use a bayonet.

The Australian Report adds that ‘it is unfair to criticise untrained troops for poor performance’ [desertion and indiscipline]. It goes on to add ‘if well trained and properly led troops run away from a defensible position, that may be cowardice; if untrained soldiers in an obviously hopeless position, crack and run when attacked [by overwhelming enemy numbers] after heavy bombardment, they cannot be blamed’.

The accusation of ‘failure to send out patrols’ had no basis. In the Wavell Report, it was acknowledged that one patrol was sent out on the night of the 8th February 1942, the very night that the Japanese invasion of Singapore Island started. The Australian Official History lists several nights when patrols had occurred in the week prior to the night of the invasion. Either the reports on these patrols did not make it to the Allied High Command, or they were simply ignored.

We know of Australian patrols before the Japanese attack – THEY reported large numbers of Japanese troops, tanks, etc massing across the Straits, those 2/4th on the beach could see them moving about quite clearly and reported such. But Percival remained committed to his belief the Japanese would advance through the north east right up until one or two days into the battle.

(It must be noted that at the time, the Allied High Command, in particular Percival was convinced that the Japanese invasion would come from the north-east side of Singapore and not the north-west where the Australians were located.)

It is clear that some instances of desertion occurred. But most Australian soldiers, as with most other allied soldiers, conducted themselves with courage and discipline throughout the Malayan and Singapore campaigns.

It should be noted that the Australian 8th Division suffered 73% of the allied casualties but only comprised 13% of the allied forces. The action of senior Australian and British military officers to place untrained soldiers at the front line, also bears greater scrutiny!

The report was based on statements from some 50 British officers and residents and compiled by the staff of the British regional commander at the time, Gen. Sir Archibald Wavell. Wavell endorsed the report describing it as ‘fair and accurate.’

One officer described in the report how the desertion of Australian troops allowed the Japanese to advance on Singapore.

‘An effort was made to drive the Japs back into the sea. Three battalions were to advance in line,’ the unnamed officer wrote. ‘But there was a battalion missing and the Japs walked through the gap. The missing battalion was an Australian battalion. It reappeared in Singapore town, preferring drink and rape to its duty.’

It is unreasonable to allow the possibility of a few to brand all Australian soldiers in the Fall of Singapore. It then falls back on the British officers who compiled the Wavell Report, as to their motive in blaming Australia. A report that was endorsed by Wavell himself as being ‘fair and accurate’.

Perhaps the last word on this should be given to the RSL at the time of the London newspaper claims, “the people [British Officers] who were making these reports were doing so to cover their own backsides”.

The Australians would have loved to have had a few tanks like this – even a few planes!

This is war.

When you lose somebody has to pay. When you win, everybody wants to be the hero.

How many officers returned home with their Official War Diary making them heroes?

It wasn’t until the 1960s onwards when the men began writing of their personal experiences did the Australian public gain a greater and honest insight into the lives of POWs.