The following is taken from the website Prisoners of War of the Japanese 1942-1945 which is maintained by Peter Winstanley. We acknowledge and thank Peter Winstanley

Nursing Sisters Account Of Life As A Prisoner Of The Japanese

Captain Ellen Mavis Hannah SX10595 – 2/4 Casualty Clearing Station

THEY HAD IT WORSE THAN WE DID

by CAPT. FRED STAHL RA Sigs 8TH DIV

(‘F’ FORCE THAILAND with LT GEN KAPPE)

I first met Sister Hannah on the “Queen Mary” en route from Sydney to Singapore, she and other members of the 2/4 C.C.S; 2/10 and 2/13 A.G.H. would be known to, and remembered with gratitude and affection by lads hospitalised during training or as war casualties. I re-established contact with Sister Hannah (as I still think of her) and have learned something of her experiences as a Jap P.O.W:

‘There is no doubt that our women-folk had it worse, in many ways, than we did. The story in her own words:—’ (Fred Stahl).

“I was on the “Vyner Brooke” from Singapore on the night of 13/14 February 1942, 65 sisters without supplies other than one case of tinned food we ourselves had carried aboard, with insufficient crew, and no hope of getting through at that stage. The Japanese Navy were attacking Sumatra, we were bombed and sunk, and I spent three days in the water. Some of us, myself included, could not swim. We lost everything, and the lives of 12 sisters were lost by drowning, plus 21 who were shot by the Japanese on Banka beach when they swam ashore. I can see Lanie (Elaine Lenore) Balfour-Ogilvy calling out to me even now – she was a strong swimmer, and the fact I could not swim saved my life. If I had been able to get to her, I too would have been shot as she was. Fate plays many strange tricks in life. Why was I the only survivor of the 2/4 C.C.S Sisters?”

(Sister Hannah came ashore near Muntok and was first imprisoned on Banka Island. She was later moved to Palembang, where she was in two different camps and was then sent back to Banka. Subsequently she was transferred to Belalau camp at Lubeck Linggau, inland from the S.W. coast of Sumatra, and was there when the war ended.)

“When we travelled by rail we were in metal trucks, the same as your “F” Force travelled in. Ours was sealed. We also were moved by ship several times. This was humiliating, as on one occasion the only toilet facilities were wooden open slotted boxes on the side of the ship, in full view of the guards and everyone else. On other occasions the ships were small and we were herded below decks onto sacks of rice with no toilet facilities. We used tins on a string which were passed up top and washed overboard – we had no food, and people who died were thrown overboard.

Food was always a problem, and the Japs supplied us with rations which were quite unsuitable – very rough vegetables, mouldy rice, practically no protein content, one egg very occasionally between six, and rarely some very small fish, which we toasted whole. I note you were issued with tea and a little sugar. Except in the very early days at Palembang camp we never received any sugar, tea or milk of any kind in our rations, nor any Red Cross chocolate. Although you received small issues of Red Cross parcels we were given none at all.

After things had settled a little in the first few months in Palembang a bullock cart with some bananas, eggs, pineapple etc. was allowed in on Sundays. However money, of course, was a problem. For at no time during the whole time of our captivity, did the Japanese give us any pay. I came ashore with 2 Malayan dollars pinned in my pocket but I had given this to a Malay who had helped me over the last quarter mile to the shore. So I worked when I could, the Dutch women in the camp had money and I made hats from the bags that our rations were delivered in, and thus earned a little to buy extra food. The Dutch women gave cloth for binding and I borrowed a sewing machine for which I was charged so much per hour. The finished articles were bought by the Dutch and the money used for my “family”, Sisters Gardam (TX2183), Raymont (TX6012), Simons and myself, this was only possible in the first few months as we were moved back to Banka Island.

The only other money we ever received was that which some of the men generously sent us, via me when I was sent into Palembang for medical treatment. On a couple of occasions I had to hoodwink the Nips and carried the money and some letters in a sanitary towel, these donations were also used by us to buy a little extra food when possible.

I didn’t realise the mental anguish which would ensue from my defiance of the Japs, someone informed on me and they found out that I was the culprit, for over 18 months the threat of being interrogated by the Kempei-Tai hung over me, and I was eventually taken to the guard house, then to a house nearby where the Kempei-Tei bullied me, hit me and tried to make me implicate others. The others of course were not implicated, except insofar that I carried letters for Dutch and English women to their husbands and returned with answers and money.

My husband Joe, a POW also, told me that in your camps (male POW camps) military discipline was maintained as much as possible. Not with us. Try to make 1000 women, mostly civilians, toe the line! ‘Tis almost impossible and they were the ‘very devil’. Your camps had a big advantage, at no time did we receive any pay, we were made to carry rice and water for the Nips, chop trees down, mend and build new huts and a thousand other things without the ‘know how’ or the physical strength necessary.

We were hit by all the usual ills of POW’s in tropical areas – dysentery, beri beri, malaria, dengue fever, dermatitis, cardiac conditions etc. We suffered from a complete lack of news where, as in most of your camps you had radios, we had none at any time, our only news came from the black market people – being very garbled, and not much of it. We received no mail, no Red Cross parcels, no clothes issued, and never issued with any medicines or drugs for the sick people in our camp.

We were the scum of the scum in the Nip’s eyes, we were starved, beaten, neglected and allowed to suffer disease without help. We were not raped – though I met later some women from Hong Kong who were – but we suffered every other form of humiliation at the hands of the little yellow beasts. At one stage early 1942 we were nearly made to submit to Japanese bestiality, but by the grace of God and our own resourcefulness we were spared this final humiliation.

I was only 4st 6lbs (approx 28 Kg) when liberated and near the end of my tether, I will never forget in 1945 the desolation when Sisters Raymont (8/2/45) and Gardam (4/4/45) died. We were so neglected and burying bodies of people who died, was so revolting that I was determined not to die there, but return home. I then realised I had hidden strength and determination I never knew existed. The comradeship of our friends was a tremendous help, they were our only family and we meant a great deal to one another.

The Japs wouldn’t reveal the position of our camp, so it was the 24th August 1945 before we were found and liberated from a miserable airstrip in Lahat in Southern Sumatra. Carrying my pack of meagre belongings and helping to carry a stretcher with a very sick POW on it, we passed 2 Nip soldiers sitting nearby smoking and grinning. Japs hate sickness and are scared of it, so I made them put their cigarettes out, stand to attention and then carry the stretcher and my bug ridden pack, giving me a great feeling of satisfaction.”

Fred Stahl.

So there it is chaps – No drugs, no radios, no tea, no sugar, starvation rations, (diet gradually curtailed to two ounces of rice a day, plus small amounts of Kong Kong and beans), no Red Cross parcels, no pay, small wonder at liberation Sister Hannah was the weight of a 9 year old girl. Discipline was very important, without it no bargaining power. It was the magnificent discipline by our men that gave the officers the extra edge in negotiating with the Nips. That preserved our morale. Finally, they were women subject to the will of enemy soldiers, an unpleasant prospect at any time.

I think you will agree, that overall, they had it worse than we did.

Fred Stahl Captain RA Sigs 8th Div QX6306 1992

Mrs Elaine Stahl (widow of Fred Stahl) in 2005 said Mavis Hannah would have been “absolutely delighted” to know her story was published on the internet. First published 8th Div Signals magazine. Vic Eddy 1992.

Captain Mavis Hannah (married name Allgrove) was born in Perth 12 October 1910. She enlisted in the AIF on 9 August 1940 at Goodwood Park , South Australia. Her discharge from the Army became effective on 2 December 1946. Her death occurred on 29 October 1993.

Article presented by Lt Col (Ret’d) Peter Winstanley OAM RFD JP. email peterwinstanley@bigpond.com website www.pows-of-japan.net

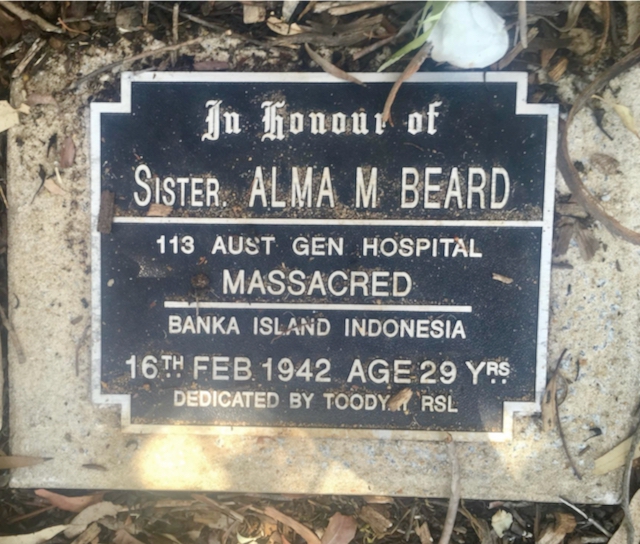

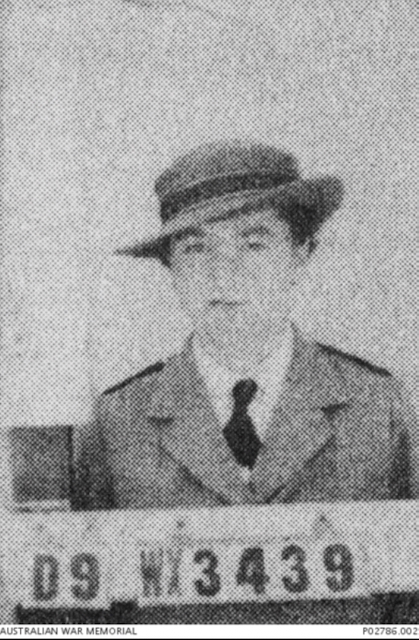

Group portrait of men and women of the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS). Identified in the second row are: (far left)TX5126 Corporal James Bevan Warland-Browne; (sixth from left) TFX2183 Staff Nurse Dora Shirley Gardam; (seventh from left) WFX3439 (W233412) Sister Bessie Wilmott; (fifth from right) SX10595 Captain Ellen Mavis Hannah; (third from right) TX3038 Sergeant (Sgt) Valentine Edward Alexander Bannerman. Before enlisting in the second AIF in 1940, Sgt Bannerman had served 16 years as an officer in the British Army. A reformed pacifist, Bannerman refused a commission in the Australian army, and elected to serve as a Non Commissioned Officer in a medical unit. The 2/4th CCS was in Singapore when it was invaded by Japanese forces in February 1942, the men and women of the unit being captured and spending the rest of the war as prisoners of war (POW). Staff Nurse Gardam, Sister Wilmott and Captain Hannah were three of 65 sisters of the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) who were on board the hospital ship Vyner Brook when it was sunk by Japanese bombers on 14 February, and were amongst the 22 who survived. Sister Bessie Willmot was killed by Japanese forces during the Banka Island Massacre on 16 February 1942, Staff Nurse Gardam being taken POW and dying in captivity on 4 April 1945. Captain Hannah was the only nursing sister from the 2/4th CCS to survive captivity and the war.

From Muntok Peace Museum

HANNAH Ms Ellen Mavis AANS Nursing Sister. Married planter Joseph William Allgrove after the war. His first wife, Marjorie (née Walden), was lost at sea on the Giang Bee. Ellen was known as Nell Allgrove in England and Mavis in Australia. Returned to Malaya post war. Retired to Dedham, Essex.

Joseph Allgrove’s first wife, Marjorie Allgrove, British, was aged 41 years when she died following the sinking of the Giang Bee, 13.2.42. She was the daughter of Mr. & Mrs. H. E. Walden of Slough, Buckinghamshire and was in the Medical Aid Service at the start of the war.

J. W. Allgrove was Manager of the Muar River rubber estate, Segamat, Batu Anam, Johore. He obtained the rank of Lance Corporal in the Johore Volunteer Engineers and was a POW (MVDB).