Commanding Officer, NX70416 Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Gallagher “Black Jack” GALLEGHAN, 2/30th Battalion

Appointed Commanding Officer of Australian POWs Singapore

by Major General Cecil Arthur CALLAGHAN 8th

Division, AIF Commanding Officer (with other senior officers was moved by sea to Formosa (Taiwan) in August 1942.

Before the fall of Singapore, Brigadier Callaghan was in command of the Royal Australian Artillery of the 8th Division located in Malaya. His immediate superior was Lieutenant General Henry Gordon Bennett who was in command of the entire 8th Division. When the British Lieutenant General Percival signed the surrender of the Allied forces on 15 February 1942, Bennett escaped from Singapore leaving Callaghan in charge of the AIF prisoners. Percival promoted him to temporary Major General of the AIF in Malaya and he subsequently met with the commanding Japanese officers. Of this meeting Griffin notes, ‘At Tanglin another justification for my work as a war artist cropped up. General Bennett with a couple of other officers had escaped the night before, leaving Brigadier Callaghan to command the AIF. It appears the insignia of a brigadier would not have been sufficient to impress the Japanese so I drew on his lapels the crossed batons of a general. Hardly had I finished this little service when up came the conqueror… I was not present at the ensuing interview, but in any case the [Japanese] officer would not have been able to see Callaghan’s lapels. He was a very tall man, the Japanese a very short one’. Callaghan was moved to Changi prison along with the rest of the AIF taken prisoner, but in August he and other senior officers were removed, leaving Major General Frederick Galleghan in charge of the AIF prisoners. Before he was liberated in August 1945, Callaghan was moved from camp to camp across Asia and he suffered greatly from dysentery and malaria.

on 15 February 1942 Lieutenant General A. E. Percival, the British general officer commanding, Malaya, decided to surrender in Singapore; a cease-fire was set for 8.30 p.m. About two minutes after that time, Bennett called on Callaghan, who was weak from a recent attack of malaria, informed him of his determination to escape and handed over the division to him. Callaghan did not approve of Bennett’s action.

Next day, when Bennett’s disappearance came to Percival’s attention, he formally appointed Callaghan commander of the A.I.F. in Malaya and promoted him temporary major general. Callaghan did all he could to raise morale and to ameliorate the appalling conditions which his men endured in Changi prisoner-of-war camp. Despite the ‘starvation diet’, he managed to set aside a three-day supply of rations as a reserve for the soldiers. He also insisted that discipline be maintained, whether in regard to smart turnouts or to punctilious saluting. Percival said of him: ‘A more loyal or courageous man I never met . . . he bore uncomplainingly his own sufferings’.

In August Callaghan and other senior officers were moved by sea to Formosa (Taiwan). There, in Karenko camp, he was beaten by the Japanese, and suffered from dysentery and malaria; his weight dropped from 13 st. 6 lb. (85 kg) to 8 st. 5 lb. (53 kg). Having been shifted to Tamasata camp in April 1943 and to Shirakawa camp in June, he was flown to Japan in October 1944 and then to Manchuria. He was freed by the Russians in August 1945.

Callaghan travelled to Morotai where he met the commander-in-chief, General Sir Thomas Blamey, to whom he delivered a letter from Percival which stated that Bennett had relinquished his command without permission. At a military court of inquiry into Bennett’s conduct, held in Australia in October 1945, Callaghan claimed that he had not immediately informed Percival of Bennett’s departure because he had ‘felt ashamed’.

Next year Callaghan reported to Prime Minister J. B. Chifley on allegations that Australian prisoners of war had been harshly treated by their own officers. Callaghan explained that officers had been obliged to act against individual offenders to prevent the Japanese from punishing prisoners en masse. On 27 January 1947, although sick in hospital, he commented on Bennett’s and Percival’s reports on the operations in Malaya; he supported Percival and found fault with Bennett’s account.

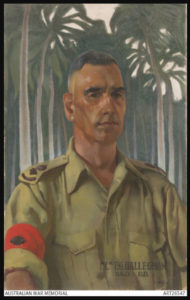

Below: ‘Black Jack’ Galleghan who was left in charge Australian POWs at Singapore. For today’s view of leadership 1942-1945 Please read further

‘Blackjack’ was fairly highly regarded by his 2/30th troops. As POWs in Changi, Singapore ‘Blackjack’ intended to see to his troop’s welfare all he could. His ‘bugger you Jack we’re all right’ attitude was not ideal with every other POW as one can well imagine.

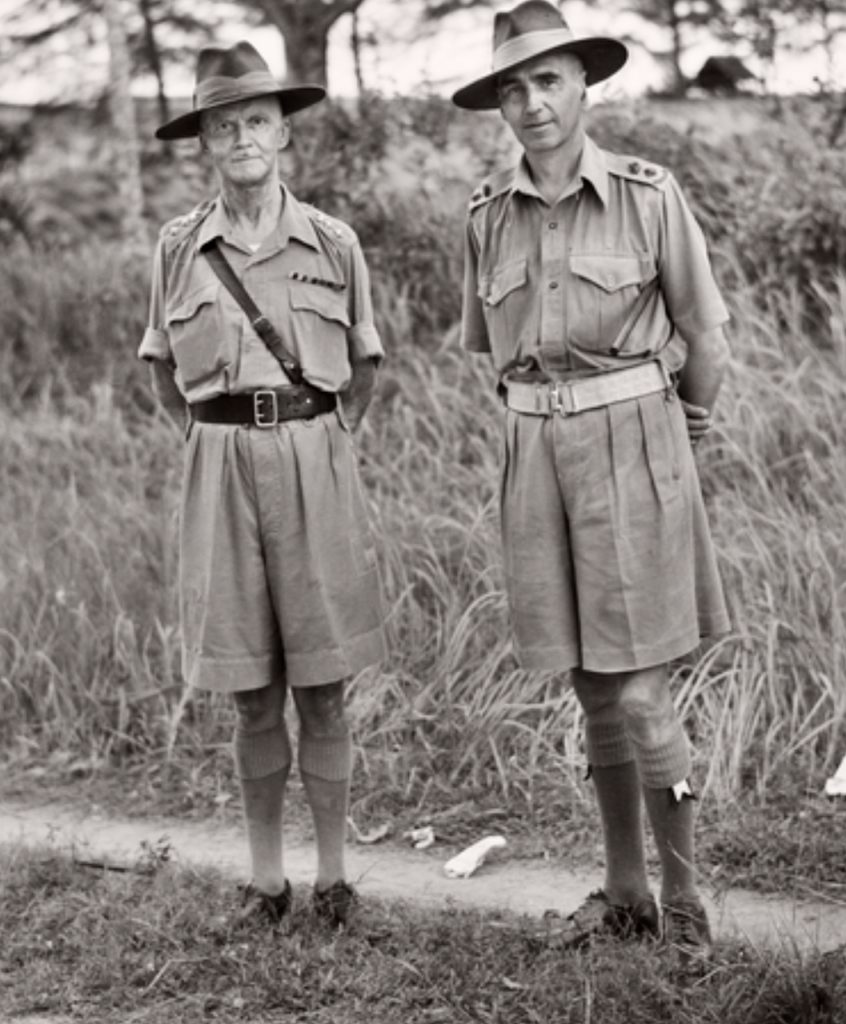

Colonel E B Holmes, Commander of British and Australian POWs, Malaya (1) with Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Gallagher Galleghan, DSO, ED, Commanding Officer, 2/30th Australian Infantry Battalion and commanding Australian POWs in Malaya

‘Cecil Arthur Callaghan (1890–1967)

This article was published:

- in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 13 , 1993

- online in 2006

Cecil Arthur Callaghan (1890-1967), army officer and merchant, was born on 31 July 1890 in Sydney, son of Robert Samuel Callaghan, merchant, and his wife Alice Emily, née Whitehead, both Melbourne born. Cecil was educated at Sydney Grammar School before joining his father’s firm which imported boots and shoes. Six feet (183 cm) tall and well built, he enlisted as a citizen-soldier in the Australian Field Artillery in 1910 and was commissioned next year. On 18 August 1914 he transferred to the Australian Imperial Force and two months later embarked for the Middle East as a captain in the 1st Field Artillery Brigade.

After training in Egypt, he took part in the landing at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. During operations on 12 July he moved forward with the infantry and, from captured trenches, established telephone communication with his battery; while continuing to advance under heavy fire, he sent back valuable reports. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. In October he went to Egypt for three weeks to organize the 5th Howitzer Battery and in December participated in the evacuation from the Gallipoli peninsula. Having transferred to the 5th Divisional Artillery in Egypt, he was promoted major and made acting commander of the 25th Howitzer Battery in March 1916.

Moving to France in June, Callaghan was posted next month to the 13th F.A.B. as a battery commander. On the Somme and in the Ypres sector (Belgium), his unit performed outstandingly in 1917, despite suffering more casualties than other batteries in the division. In March 1918 he was promoted temporary lieutenant colonel and placed in command of the 4th F.A.B., 2nd Divisional Artillery. After serving in June as a liaison officer with French troops at Villers-Bretonneux, in the final advances (August to November) he ‘commanded his brigade with marked success’. Appointed C.M.G. and to the French Légion d’honneur in 1919, Callaghan was mentioned in dispatches four times. He sailed for Australia in July and his A.I.F. appointment terminated on 22 January 1920.

Resuming his civilian occupation and his Militia service, Callaghan had charge of the 3rd (1920-21) and the 7th (1921-26) Field Artillery brigades. On 1 May 1926 he was promoted temporary colonel and given command of the 2nd Divisional Artillery; for five years his divisional commander was Major General H. G. Bennett. A substantive colonel from 1929, Callaghan commanded the 8th Infantry Brigade in 1934-38. He was made brigadier, Royal Australian Artillery, Eastern Command, in November 1939. On 1 July 1940 he was selected to be commander, Royal Australian Artillery, in the A.I.F.’s 8th Division; in September Bennett again became his immediate superior. Callaghan visited Malaya in June next year to investigate command problems in the division and arrived in Singapore in August to assume his duties.

In November-December 1941 he administered the division while Bennett acquainted himself with A.I.F. operations in the Middle East. The Japanese landed at Kota Bharu, Malaya, on 8 December. To meet a possible threat to Endau, Callaghan altered the disposition of Australian units. On his return, Bennett strongly disapproved of the changes and ordered the resumption of the previous positions. Throughout the fighting in Malaya, Callaghan’s regiments gave fine support to the infantry. Nonetheless, the overall situation deteriorated so rapidly that on 15 February 1942 Lieutenant General A. E. Percival, the British general officer commanding, Malaya, decided to surrender in Singapore; a cease-fire was set for 8.30 p.m. About two minutes after that time, Bennett called on Callaghan, who was weak from a recent attack of malaria, informed him of his determination to escape and handed over the division to him. Callaghan did not approve of Bennett’s action.

Next day, when Bennett’s disappearance came to Percival’s attention, he formally appointed Callaghan commander of the A.I.F. in Malaya and promoted him temporary major general. Callaghan did all he could to raise morale and to ameliorate the appalling conditions which his men endured in Changi prisoner-of-war camp. Despite the ‘starvation diet’, he managed to set aside a three-day supply of rations as a reserve for the soldiers. He also insisted that discipline be maintained, whether in regard to smart turnouts or to punctilious saluting. Percival said of him: ‘A more loyal or courageous man I never met . . . he bore uncomplainingly his own sufferings’.

In August Callaghan and other senior officers were moved by sea to Formosa (Taiwan). There, in Karenko camp, he was beaten by the Japanese, and suffered from dysentery and malaria; his weight dropped from 13 st. 6 lb. (85 kg) to 8 st. 5 lb. (53 kg). Having been shifted to Tamasata camp in April 1943 and to Shirakawa camp in June, he was flown to Japan in October 1944 and then to Manchuria. He was freed by the Russians in August 1945.

Callaghan travelled to Morotai where he met the commander-in-chief, General Sir Thomas Blamey, to whom he delivered a letter from Percival which stated that Bennett had relinquished his command without permission. At a military court of inquiry into Bennett’s conduct, held in Australia in October 1945, Callaghan claimed that he had not immediately informed Percival of Bennett’s departure because he had ‘felt ashamed’. Next year Callaghan reported to Prime Minister J. B. Chifley on allegations that Australian prisoners of war had been harshly treated by their own officers. Callaghan explained that officers had been obliged to act against individual offenders to prevent the Japanese from punishing prisoners en masse. On 27 January 1947, although sick in hospital, he commented on Bennett’s and Percival’s reports on the operations in Malaya; he supported Percival and found fault with Bennett’s account.

Mentioned in dispatches and appointed C.B. (1946) for his leadership and devotion to duty while a prisoner of war, Callaghan was promoted major general in 1947 (with effect from 1 September 1942) and placed on the Retired List on 10 April. He was active in the Returned Sailors’, Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Imperial League of Australia, and a founder of the Ku-ring-gai sub-branch. Callaghan was particular about dress and his involvement in the footwear industry earned him the nickname, ‘Boots’. He had a very good memory and retained his strong faith in Christianity. After a long illness, he died, unmarried, on 1 January 1967 at Gordon and was cremated with Methodist forms. The 8th Division Association honoured him with a memorial service.’

‘Sir Frederick Gallagher Galleghan (1897–1971)

This article was published:

-

in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 14 , 1996

-

online in 2006

Sir Frederick Gallagher Galleghan (1897-1971), army officer and public servant, was born on 11 January 1897 at Jesmond, New South Wales, son of native-born parents Alexander Dunlop Galleghan, crane driver, and his wife Martha, née James. Educated at Cooks Hill Superior Public School, Newcastle, Frederick was a studious lad. In August 1912 he joined the Postmaster-General’s Department as a telegraph messenger; fascinated by all things military, he resolved that he would one day exchange his red cap for that of a senior army officer.

After seven years in the cadets, on 20 January 1916 Galleghan enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force. Posted as a corporal to the 34th Battalion, he sailed for England in May. Six months later he was promoted sergeant and sent to the Western Front. Twice wounded in action (June 1917 and August 1918), he was invalided home and discharged medically unfit on 3 March 1919. That he had been denied a commission in the A.I.F. put a chip on his shoulder which gave rise to a tendency to ride rough-shod over officers junior to himself.

At the Baptist Tabernacle, Cooks Hill, on 18 November 1922 Galleghan married a theatre employee Vera Florence Dawson (d.1967); they were to remain childless. Having been employed on clerical duties in the post office, in 1926 he transferred to the Department of Trade and Customs, and in 1936 to the investigation branch of the Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department, Sydney. In September 1919 he had been gazetted temporary lieutenant in the Militia. A lieutenant colonel by 1932, he successively led the 2nd-41st, 2nd-35th and 17th battalions. He joined the A.I.F. on 18 March 1940 and on 17 October was appointed commanding officer of the 2nd/30th Battalion, 8th Division.

Galleghan wanted his battalion to be, and to be seen to be, the embodiment of all that was finest in the Australian army. To achieve his aim, he ordered strenuous training and spared no one—officers, men, or himself. In July 1941 the unit sailed for Singapore. On 14 January 1942 at Gemas, Malaya, Galleghan conducted a brilliant ambush of a superior Japanese force. For his part in the encounter and the subsequent well-executed withdrawal, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. He became a prisoner of war when the British surrendered on 15 February. With the removal of senior officers from Singapore in August, he assumed command of the A.I.F.; from March 1944 he was deputy commander of all allied prisoners in Malaya. It was for his role at Changi that he was to achieve lasting fame.

Known as ‘Black Jack’ because of his dark complexion, black hair and piercing brown eyes, Galleghan was a formidable figure, six feet (183 cm) tall, erect, and with a rock-like countenance. His stern expression and military bearing radiated an aura of command. One junior officer represented many when he wrote: ‘We were far more frightened of ”B.J.” than of the Japanese’. ‘His personality’, said another, ‘left no room for half measures. He did not necessarily seek your regard or goodwill’. Somewhat surprisingly, his harsh discipline earned him the affectionate respect of his men and the grudging admiration even of those who felt the full weight of the occasionally unreasonable exercise of his authority.

Galleghan realized that survival depended on morale and that discipline was the basis of morale. His strict orders—thought by some to border on the absurd for a prisoner-of-war camp—saved countless lives. It was his fate to be remembered most for what he valued least. ‘You are not going home as prisoners’, he barked in his husky voice, ‘you will march down Australian streets as soldiers’. Back home in October 1945, he refused to associate with prisoner-of-war organizations and urged his old battalion to follow his example. In taking this stand he probably did the survivors of the 8th Division a disservice.

Mentioned in dispatches, Galleghan was promoted colonel and temporary brigadier (with effect from April 1942) before he transferred to the Retired List on 3 January 1946. In the following year he was appointed O.B.E. He had been raised to inspector (1945) in the investigation service and in 1947 became deputy-director, in charge of the Sydney office. In 1948-49, as honorary major general, he headed the Australian Military Mission to Germany. Displaying an unexpected gift for diplomacy, he chaired the fourth session of the general council of the International Refugee Organization, served on its executive-committee and helped displaced persons to emigrate to Australia. On his retirement from the public service in 1959 he was appointed I.S.O. He was honorary secretary (1959-70) of the Royal Humane Society of New South Wales, State chairman (from 1963) of the Services Canteens Trust Fund and an honorary colonel (1959-64) of the Australian Cadet Corps.

‘Black Jack’ always remained the battalion commander, even wearing a miniature colour patch of the 2nd/30th on his major general’s uniform. He had a softer side which, for the most part, he took pains to conceal: when his men returned to Changi from the Burma-Thailand Railway he had been so moved by the toll of death and the desperate condition of those huddled before him that he was unable to speak and in tears marched silently between their lines. In 1969 he was knighted for his services to war veterans. On 8 December that year at St Clement’s Anglican Church, Mosman, he married a widow and State commandant of the Voluntary Aid Service Corps, Persia Elspbeth Porter, née Blaiklock; Sir Frederick’s old soldiers showed their pleasure by calling him ‘The Shah of Persia’. Survived by his wife, he died on 20 April 1971 at his Mosman home and was cremated with Anglican rites.’