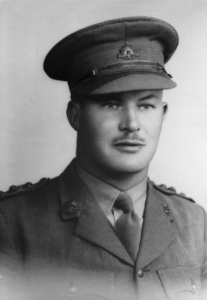

Dr Albert Coates WX503645 was one of 43 Australian doctors, 6 dentists and 458 medical orderlies who became POWs and worked on the Burma-Thai Railway, WWII.

He was a remarkable man. He was also an idealistic, highly experienced and dedicated surgeon when he enlisted for service in WW2. His experience included service in WW1. His life story is an inspiration for every Australian.

‘Albert Coates was extraordinary from the start. Born in 1895, he was the first of 7 children. His grandfather arrived from England during the Victorian goldrushes, and they settled in the Ballarat area. As the family was of modest means, when young Albert completed his primary school, he was sent to work, initially apprenticed at 12 years old to a butcher, then to a book-binder, the latter giving him access to books to read. He was noted to be bright, and his primary school teacher, Mr Leslie Morshead , later Lt-Gen Sir Leslie Morshead, CO 9th Div AIF, offered to teach Albert at night school. He studied languages and sciences, and at 18 years sat the matriculation equivalent, receiving 5 distinctions. He left his apprenticeship and obtained work at the Melbourne and subsequently Wangaratta PO while he studied pre-med subjects to facilitate his enrollment in the University of Melbourne medical school.

In 1914 world war broke out, and shortly after young Albert enlisted in the AIF. He was considered too short for combat and so was eventually given the role of medical orderly. He was sent to Egypt in the first convoy from Albany, and he continued to learn various languages from the troops and civilians he met. His French and German became fluent. He was present at Gallipoli landing but the horses and wagons of the medical teams were not landed, and he watched from the ships for 18 long days before returning to Alexandria. When he eventually got onto the peninsular he served there for many months, until the final Australian evacuation in 1915. He continued service in Ypres and on the Somme. As a medical orderly in WWI he witnessed first-hand the horror that war brings. He taught himself Dutch and as his language skills became prominent, he was drafted for intelligence work. The British Army subsequently offered him a commission in the Intelligence section, after nearly executing him themselves in error.

The young Sgt Coates returned however to Australia late 1918, enrolled at University, worked at the Post Office at night to put himself through medical school. He married in 1921 while a medical student. He graduated in 1924 with 1st class Hons in all subjects. He became a RMO at the Melbourne Hospital, and soon showed aptitude for anatomy and surgery. He was given the position of Stewart Lecturer in Anatomy in 1926. He subsequently became a specialist surgeon, joined the honorary staff at Melbourne Hospital, both working and teaching. . One of his students, and later staff colleagues, was ‘Weary’ Dunlop. His professional life blossomed, the only shadow in his life occuring in 1934 when his wife died after an operation. It was some time later that he remarried.

In 1939 war was declared again, and despite being nearly 45 years old, with 5 children to support, he enlisted in the 2nd AIF. The 8th Division sailed for Singapore in 1941, and Lt-Col Coates aboard the Queen Mary was Senior Surgeon of the 10th AGH in Malacca.

In Malacca, he learned about tropical medicine first hand. Under Col E R White, clinical meetings were begun and the staff studied tropical ulcers, amoebic dysentery, malaria and other tropical syndromes in depth. Coates got permission, after much official resistance, to train a number of medical orderlies here. They eventually proved to be a great asset when the invasion came as most of the nurses were evacuated.

During his time there, Coates was called to Singapore to perform emergency surgery on Australia’s Ambassador to Japan, Sir John Latham. He subsequently accompanied him to Melbourne to conduct definitive surgery for him. They became great friends. Coates managed three short weeks with his family before being urgently recalled to Malaya.

By January 1942, the Japanese were advancing quickly on Singapore, and the 10th AGH in Malacca was broken up. Coates was sent to 13th AGH in Singapore and he operated there on the troops returning from the advancing war front. The hospital filled rapidly, patients even being nursed on the lawns. Unfortunately for the hospital, a battery unit was setup at one end of the garden and soon air- raids were occurring daily. Bombing around the hospital more than once meant pieces of roof would descend into the middle of the operating theatre. They often operated in total blackouts.

One case Coates recalled of that time was a soldier with a sword cut from neck to buttock. While he was being sewn up he told Coates that he had, despite his fearsome wound, successfully dispatched his samurai assailant.

In the four weeks before the British surrender and the Australians were ordered to lay down arms, 1789 Australians were killed in action in Malaya and another 1306 wounded.

When Singapore fell Coates was evacuated under mortar fire aboard the ship Sui Kwong with a large body of mainly British troops on a ship towards Java. The ship was bombed en-route and sunk, the majority of the troops being landed by life-raft on Sumatra.

On arrival at Tembilahan, he operated on the worst 15 casualties and put them in native huts. Much of the party then left for Australia, but Coates stayed to tend to the sick and injured. He performed over 100 operations in the next week in a small Indonesian hospital. As more casualties began arriving, they moved up-river and operated at a mission hospital at Rengat. They then began a journey toward Padang, across country. Many of them had only the clothes in which they stood, no boots, and they had to sleep out. Like many of them, Coates not surprisingly, got his first bout of dengue fever here. He was one of two doctors, and the only surgeon, for the 1500 troops, with about 50 serious cases. He was required to operate at various places at which they stopped through this journey, using local Dutch facilities. Another case he noted at this time was a woman with a large shrapnel wound of the buttock, which had severed her sciatic nerve, and associated pelvic abscess. Coates drained the abscess, and repaired the nerve as best he could in the village hospital. He met the woman after the war and was pleased to note she had only a slight drag of her toe. He had through this time, several chances to be evacuated but chose to continue to support and care for the troops in his immediate care, who otherwise would be left without any surgical care. Unfortunately by the time they reached Padang, the Japanese had captured Sumatra, and they were surrendered to the Japanese there. It was here that Coates received his first beating from the Japanese soldiers.

In May 1942, Coates with 500 British and 1000 Dutch POW, were sent to Medan and loaded onto a small coastal steamer and sent to Burma to join the 3000 Aussie POW of A-force who had been sent from Changi.

‘In Burma, Coates was responsible for the major and some minor camps. He worked with Lt Col Hamilton, SMO, as well as Majors Ted Fisher from Sydney, Allan Hobbs and Sydney Krantz from Adelaide and W E Harris, a Brit. Fisher treated Coates for amoebic dysentery in Tavoy, luckily when some of the small supply of emetine was still available. He became a close companion and physician in the latter days of captivity. A large proportion of the Sumatra prisoners developed acute fulminant amoebic disease and many died. Two Dutch doctors Coates later recalled there were Maj Neileson and Capt Slaghter. Initially in Mergui, then in Tavoy, where camp base-hospitals were located, Coates performed a large number of operations. At one point it included finishing a botched appendix operation that the Japanese doctor was doing on one of their own men. He was stuck, and Coates finished the operation, allowing for some face-saving. The embarrassed Japanese doctor later gave him a tin of condensed milk and a pack of cigarettes, and an Aussie wag commented that it was probably his lowest fee ever.

An innovation at this time was the use of an ileostomy for amoebic dysentery. A Dutch soldier had developed peritonitis from a bowel perforation, and Coates performed this life-saving operation which was still somewhat experimental at that time. A flattened water bottle was adapted to cover the stoma. Coates was pleased to close the stoma on the same man two years later in Nakhon Pathom. This operation and the appendicostomy favoured by ‘Weary’ Dunlop became the standard treatments for toxic amoebic disease in the absence of specific medical therapy.

In February 1943, as the plans for the railway progressed, he was moved to Thanbyuzayat and first met the infamous Korean guards who would become such a torment for the POW. On the night before leaving with the last POW, mostly sick or incapacitated, with no equipment, Coates performed a successful appendicectomy on a POW using only a razor blade. An improvised stretcher was made for the patient to be carried on. They were then sent up the track, initially to Reptu at 30 kilo, where the “light sick” were housed. These were men who the Japanese considered not too sick for work, having only malaria, and malnutrition, although many could hardly stand. He reported the death rate amongst the native labourers was very high already here, bodies lay around commonly. At the 75 kilo camp conditions were the same and at one point of 1300 very sick men, the Japanese ordered 1000 to work.

While at 75 Kilo camp, and working as solo doctor, Coates was incapacitated with scrub-typhus and many of the men thought he would die. Although he could not stand, the Japanese sent him to run a new hospital camp 55 kilo at Kohn Kuhn where the main body of sick and injured would be taken. He was so sick, he had to be carried around the site while construction was completed and he examined the sick. He was forever grateful to two men who looked after him during his illness, Harold Buckley, who was suffering from malaria himself, and a Dutchman, Capt C J Van Bentinck who also provided great care.

This 55 kilo camp was to become a 1800 bed hospital camp for men too sick to work from up the line. Bamboo huts were constructed and a small operating theatre added, covered over with palm thatch, dirt floors, and bamboo table for surgery. There was no equipment, no supplies, as the Japanese refused to allow any, and no beds. They had no proper instruments, only a few artery forceps, a scalpel or two, sharpened table knives for amputations, bent forks for retractors, some darning needles, a kitchen saw and a curette which the Japanese had given as a joke. Coates had a spinal needle, which became the method for giving anaesthesia. There was no general anaesthesia and for minor procedures, like removing a gangrenous toe, no anaesthetic was available at all. Cleaning a leg ulcer meant three men holding down the patient. Saline irrigation was generally used to help clean the ulcers although the Dutch doctors favoured the use of maggots, and in Thailand by the Kwai Noi, patients immersed their limbs so the fish could clean the wounds. There was an initial small supply of quinine, no other drugs, just some meagre supplies that had been carried by POW. They began to make sutures from the lining of the gut of the water buffalo that were occasionally killed to make the meagre gruel. Thin strips were cut and washed, and soaked in iodine solution for a week before use.

When Coates recovered enough from the scrub-typhus he commenced surgery immediately and performed a wide range of operations here. Strangulated hernia reduction, tracheostomy for diphtheria, and ileostomy for toxic amoebic dysentery were all done here. The complications of tropical ulcers was ever present, one orderly who scratched his hand during a night-round of the patients developed gas gangrene and required an amputation. Coates performed 120 amputations for gangrenous lower limbs here. The judicial use of the curette probably saved many more limbs. Sometimes more than 50 men would have ulcers curetted in a day.

There were twelve Australian doctors and two dentists already with this force. Initially there were rumours of road construction but it then became apparent that the Japanese wanted to build a railway from Thailand to Burma and that they intended to use the POW to do it in contravention to international conventions on POW. Little did they know then that the Japanese had no interest in the well being of the POW, in fact quite the contrary. The Japanese officers viewed the starvation, torture and neglect were justified in the service of their Emperor.

Brigadier Varley was in charge of ‘A’ Force, and they were joined by more POW by Jan 1943. At the Thai end, 600 British POW under Major Sykes arrived in June 1942, and were soon joined by 3000 more British POW by August. The first teams had to build large camps at the ends of the line, smaller working camps in the jungle, and commence preparations for the work on the railway.

Albert Coates was the senior surgeon at the Burma end, working under Lt-Col Thomas Hamilton, SMO. ‘Weary’ Dunlop, was a senior surgeon and CO for the first group of Australian POW to reach the southern end in Thailand in January 1943, the force pushed forward and later known as ‘Weary’s 1000’. In all, about 13,000 Australians worked on the railway, among some 60,000 POW and about 200,000 conscripted native labourers from various Asia countries.

Some 2646 Aussie POW died among the 13,000 POW deaths in total, and at least 80,000 Asian labourers. The lower rate of deaths amongst POWs can be attributed to the presence of about 150 doctors, many British, 43 Australian, with some Dutch and one or two Americans, and the many medical orderlies, mostly volunteers, who worked on the railway, spread from Thailand to Burma, and who treated the injured and sick, and gradually developed systems for minimising infectious disease.

We wish to acknowledge the above information has been taken from ‘Prisoners of War of the Japanese 1942-1945’

Researched by Lt. Cil Peter Winstanley OAM RFD (Retired)’

We acknowledge and hank Lt Winstanley for the above informing which we have taken directly from his webpage.

We recommend reading Biography of Sir Albert Coates (1895-1977)

https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/coates-sir-albert-ernest-9772

WW2 Aged 47 years Coates was appointed Senior Surgeon, 8th Division, Australian Army Medical Corps with the rank of Lt. Colonel on 1 January 1941. He was posted to 2/10th Australian General Hospital stationed at Malacca, Malaya.

Below: Australian Nursing staff of 2/10th AGH, Malacca.

The above map shows Malaca (Mklaka) and the distances from Penang and Johore.

The jungles of Malaya were supposed to act as a deterrent to the invading Japanese.

However the Commonwealth Forces (made up of British, Australian and Indian troops) were soon forced to retreat. 2/10th AGH was quickly evacuated south, and finally to Singapore.

‘Coates saved more POW’s lives than any of the other doctors in the prison camps, through his use of improvised techniques and amputations. Many more were saved by his leadership, encouragement and example. To the brutalised POW’s he was simply known as Bertie.’

‘Albert Coates reflected that his greatest work was done in the appalling conditions of the Prisoner-of War camps on the Thai-Burma Railway.’

As a young child Albert finished school at 11 years of age and apprenticed to a butcher for whom he had already worked weekends and before school. This job lasted until Albert accidently damaged the butcher’s cart. Albert was one of seven children brought up at Mt Pleasant, Ballarat. He was a gifted student and developed an ambition for a career in medicine. To get into university at that time you had to study in church schools or through independent teachers.

Albert was fortunate to join the Ballarat Litho and Printing Company and indentured as a book binder at six shillings a week. This allowed him to attend night school and for a very low fee engage a former teacher to coach him, eventually gaining five distinctions in the 1913 Junior Public Examination. This qualified him for enrolment at Melbourne University.

As he could not afford to take his place at university, Albert moved to Wangaratta, working in the Postal Department and studying in his spare time.

By 1914 Coates was in a position to start medical school. His plans however were put aside when WW1 broke out and the idealistic 19 year old enlisted as a medical orderly attached to 7th Battalion 1st A.I.F., spending his time on-board ship heading to Europe assisting the doctor inoculating men against typhoid.

His first destination was Egypt. Encamped at Mena, Cario. Albert’s main task was transporting medical supplies and wounded in a horse drawn cart. He was also able to continue his love of languages and enrolled at the Berlitz School. He began studying and learning German on the ship’s voyage from Australia. In Egypt he included Arabic. He studied Latin and French at school.

In April 1915 Coates was on board one of the ships at Gallipoli and watched horrified as the men in the first landings were cut down. He was later at the Somme performing his medical duties in the gas warfare and trenches. It was here his linguistic ability was recognised and was soon transferred to Army intelligence as the Battalion’s interpreter.

He took leave from France and travelled to Australia returning to Europe soon after with other Anzacs in October 1918. The war ended a few weeks later on November 11.

Following the end of WW1 Coates returned to Victoria, finally enrolling to study medicine between 1919 and 1924. However it was necessary to continue employment with the Post Office working at Spencer Street from 10pm to 6.00am!

In 1924 he was offered the Stewart Lectureship in anatomy, an opportunity for further study and develop his teaching ability.

Albert gained his Doctor of Medicine degree in 1926 and Master of Surgery in 1927 and was appointed Honorary Surgeon to Outpatients at the Melbourne Hospital the same year.

Throughout the depression years his work load in outpatients and emergency surgery was extraordinarily heavy and Coates earned recognition for his work and teaching.

His interest in neurosurgery took him overseas in the mid 1930’s. On his return Coates assisted to set up a neurosurgical unit. By 1940 a group of surgeons and Albert established the Neurosurgical Society of Australia.

Albert Coates was one of Australia’s earliest neurosurgeons, based in Melbourne.

Dr Claude Anderson WX3464 of the 2/4th, fondly known as ‘Pills’ assisted Albert Coates with about 60 amputations, some of which were 2/4th men. (Basil William James Clarke WX9136).

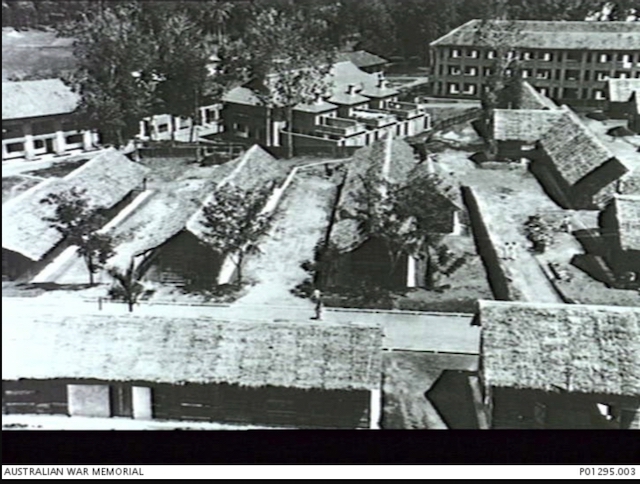

The Japanese sent trained Surgeon Dr. Albert Coates from 105 kilo to 55 kilo camp to Kohnkan to establish a 1800 bed hospital camp for men up the line who were too sick to work.

Coates was very ill a the time with scrub-typhus and had to be assisted to stand.

Bamboo huts were constructed. A small operating theatre was built to the side furnished with a bamboo table for surgery. The floors were dirt and the roof made of thatched palm.

There was no equipment, supplies nor beds. With no proper instruments Coates and his team improvised with a few artery forceps, scalpels and sharpened table knives for amputations. They used bent forks for retractors, a kitchen saw and darning needles. The Japanese jokingly gave them a curette. Coates had a spinal needle which he used to give anaesthetics. There was no general anaesthesia for small procedures such as small amputations (toes) nor cleaning of ulcers (3 men would hold down the patient to clean the wound with spoon, knife, etc).

As soon as Coates was sufficiently well he commenced work; performing a wide range of surgery including tracheostomy for diphtheria, ileostomy for toxic amoebic dysentery, strangulated hernia reduction and complications of the ever present tropical ulcer. Coates performed 120 amputations for gangrenous lower limbs and sometimes more than 50 men a day would have ulcers curetted.

Dr John Gibbon was initially the only doctor to assist Coates until Claude Anderson arrived.

Please read further from 2/4th men

Coates could always be heard saying to the sick

“Your ticket home is in the bottom of your dixie”

“Every time it is filled with rice – eat it. If you vomit it up again, eat some more; even if it comes up again some good will remain. If you get a bad egg, eat it no matter how bad it may appear. An egg is only bad when the stomach won’t hold it.”

Please read about Khonkan 55km Hospital Camp

Albert Coates.