Khonkan 55 km Hospital Camp - Burma

KHONKAN 55 KM HOSPITAL CAMP, BURMA – opened 30th July 1943 – 24 December 1943 – Hospital Camp for ‘A’ Force (also F & H Forces)

When it was decided to set up this hospital at 55km, the sick from 105km and 108 km were transferred back to this camp. Brigadier Varley, Commander of ‘A’ Force suggested the men from Meiloe 75 km Camp also be moved back to Khonkan by road and rail under the command Dr. Coates.

“Dr. Coates was remarkable; he was admired by everyone and was very efficient.”

Coates was to Burma what Dunlop was to Thailand – each being a fine surgeon in his own right. Coates was brilliant senior surgeon.

In 1914, WW1 Coates enlisted in 7th Battalion as a medical orderly serving a year on Gallipoli. He was one of the last to leave the peninsula on the night of 19/20 December 1915. The 7th battalion transferred to France in March 1916 fighting in the battle of the Somme.

A skilled linguist Coates came to the attention of his superiors and in February 1917 was attached to the intelligence staff, I Anzac Corps.

Sir John Monash and British authorities recognised his ability and, at the end of the war, he was invited to apply for a commission in the British Army. Coates preferred to go home to Australia. He then studied medicine.

Captain Claude Anderson of 2/4th was one doctor working here between 1st September to 19th October 1943 whilst Albert Coates was present (after which he returned to Aungganaung 105km Camp).

In July 1943 Dr Albert Coates was sent as Senior Medical Officer to take charge of the hospital; remaining there until end of December 1943. Khonkan was an abandoned working camp of eight bamboo and atap huts with floors of bamboo strips. It was nothing more than a series of huts previously used to accommodate railway workers.

On the 1 Jul 1943 Eric Fraser WX6506 was one of those who assisted Coates part of the way to Khonkan 55km Camp, carrying him on a stretcher.

Arriving at 55 Kilo Camp Coates was carried to his hut on a stretcher. He had travelled partly by train and truck from 75 Kilo Camp. At 75 Kilo camp Coates had became seriously ill with scrub typhus and owed his recovery to two dedicated Australians and a Dutchman who washed and fed him as he lay in rags on his bamboo bed for two weeks. His weight in Malaysia of 12 stone was reduced to 7 stone.

Please read further about scrub typhus

55 Kilo camp had been opened by Major Charles O’Brien as administrative officer and Lieutenant W.W. Tilney as adjutant on 1 June 1943. Captain J. Higgins was initially the only doctor at Khonkan. For the first two weeks Albert ‘Bertie’ Coates was carried around on a stretcher to see patients, and it was during this time he realized amputation was the option to save the lives of ulcer patients.

There were 800 patients of which 500 suffered from medium to large leg ulcers. Of course the men also suffered malaria and other illnesses such as beri beri – prevalent throughout the entire length of the Railway.

Camp rations were very scanty. The Japanese would weigh every man regularly to determine the total weight of all men in the camp. They allowed 1,200 units of rice for each man and then calculated the total amount required.

The huts at Khonkan were in a very bad state of disrepair. There were not sufficient men in the working party well enough to repair the leaking roofs. The downpours were frequent and rain came through the roofs. This seemed not to matter much to the men who had no clothing and were so ill and simply overwhelmed with suffering. With continuing illnesses the total weight of the camp became less and less. And in turn, under their ratio the Japanese provided less and less food.

Rather than less rations, what the sick needed was more as the men were starving.

As the men on the railway dropped out sick from other working camps on the railway they were sent to 55 Kilo Camp. The sick men arrived in trucks being too ill to walk. The Japanese refused to allow them to travel to a base hospital camp where there was at least some hospital equipment. Their supply of drugs and instruments may well have been minimal but it was more than that of 55 Kilo Camp – they had zero.

There were 1800 patients with malaria with a quinine supply sufficient for 300 patients. Coates protested to the Japanese medical authorities at Thanbyuzayat.

The Japanese pointed out that they allowed a man to have only one disease! If a man had malaria then he couldn’t have a leg ulcer, and if he had a leg ulcer then he couldn’t have dysentery!

Many POWs had three or more diseases. Malaria was the underlying cause of blood destruction (anaemia) and consequently those men suffered from other diseases. Quinine was the only drug available and supplies were intermittent and sometimes not available at all throughout the Camps. As important was the lack of food.

330 of the 1600 patients died.

Luck improved a little for Coates when Dutch chemist Captain van Boxtel, previously a photographer with the Dutch Air force arrived at the Camp. Coates requested the chemist prepare cocaine from some tablets which he still had with him. This was successfully used for spinal injections for amputations; as Coates wrote “in the next few weeks 120 legs came off”. Many toes were removed with scissors and without anaesthesia!

CAPTAIN C. J. VAN BOXTEL, NETHERLANDS EAST INDIES AIR FORCE WHO WAS EMPLOYED AS A CHEMIST AT 55 KILO CAMP HOSPITAL

Coates had already realized that it was useless to work with orthodox methods of amputation as practiced at home and in hospitals. In these jungle conditions the operations were similar to those done in the days of Nelson and Wellington. Indeed it was field surgery with the advantage in some cases of having some pain-relieving anaesthetic!

Ligatures were made of catgut from the peritoneal coat of the intestine of the yak and skin was sterilized with alcohol prepared by van Boxtel from Burmese brandy and waste rice.

In time four medical officers assisted Dr Albert Coates including senior doctors Major Fisher and Capt. Brereton (who went blind after the war from vitamin deficiency). Every morning he supervised these officers to segregate the sick from the very sick. They worked particularly on the leg ulcers. Coates and his medical team were curetting 70-80 ulcers every morning and supervising the dressing by dedicated volunteer orderlies. In the afternoons he would proceed to amputate 9-10 legs.

Conditions in the Camp were appalling.

The operating theatre was a bamboo lean-to about 6 feet by 8 feet. Coates had three instruments – one knife, two pairs of artery forceps and used the one and only camp saw shared with the carpenters and butcher. There was a tiny amount of cocaine that Coates used in small quantities as a spinal anaesthetic.

Survival rate was not good. If the men survived they usually faced other illnesses and without sufficient food it all seemed too hopeless for so many.

The daily procession to the nearby graveyard reminded the emaciated skeletons who were once men that death would soon end their pain and misery. Gangrenous leg ulcers constantly emitted a nauseating stench from which no one escaped.

In November 1943 Reptu 30km Hospital Camp was closed and patients transferred forward to Khonkan 55km Camp.

As Senior Medical Officer Coates visited other Camps from time to time including 50km Camp in the later stages of 1943 where conditions were worse because they had absolutely no medical equipment and were unable to amputate legs. Also the POWs had marched long distances to 55Km. They came from Thailand and included men from H and F Force.

Coates describing amputations at Khonkan 55km Hospital Camp in 1943 in his book

“The Albert Coates Story” by Albert Coates & Newman Rosenthal

Coates was sent to Khonkan Hospital Camp early April 1943 as Senior Medical Officer and initially the only doctor. He arrived on a stretcher from 30km where he had suffered scrub typhus and been seriously ill. 100s of POWs arrived at 55km Hospital – large numbers with advanced ulcers usually with underlying illnesses such as beri beri, malaria, etc.

When Dutch chemist Capt. Van Boxtel arrived at 55 km Coates asked this capable man if he could turn some of Coates remaining tablets into cocaine to use for spinal injection. This he did – supplying sterilised measured quantities in discarded cholera bottles.

Coates knew he had no other option other than to attempt amputation of the gangrenous legs. Patients would otherwise die.

He remembered his student and post-student days and the work of Ambroise Pare (1510 – 90) and John Hunter (1728 -93). Pare lived in an era when amputation was an extension of barbering! French surgeon Pare joined the French army as a barber-surgeon. He devised artificial limbs and the technique of binding arteries after amputation instead of cauterising them with a red-hot iron. (As we see in movies!)

Please read further about John Hunter

Hunter entered the British Army as a staff-surgeon, regarded as the founder of scientific surgery. Hunter wrote extensively on his experiences, contributing to understanding the results of removing of a diseased organ which might otherwise infect the whole body resulting in death or chronic illness.

Patients with penetrating ulcers of the leg were dying of haemorrhage. The ulcerating process was eating into the main artery and the men were bleeding to death.

Khonkan Hospital had no medical equipment and few medicines – hardly a hospital it was atap huts with bamboo benches set in the jungle often leaking in the wet weather. It was filthy and essential food rations minimal and poor quality – conditions no better than for Pare and Hunter.

The hospital was forced to share only camp saw with the POW kitchen and Camp carpenters – Coates scheduled amputations for the afternoons.

He adopted the Listerian circular amputation – a cut around the leg, then coning out the flesh and bone (not too much flesh on these POWs wrote Coates!)

According to Coates description:

-

The result was a cut stump, like the open mouth of a fish from in front backwards.

-

This was then loosely stitched with cotton and a bit of rag (usually the patient’s pants boiled for sterilisation) and inserted in the lower end of the wound for drainage purposes.

-

Large arteries were ligated with the camp’s home-made catgut -not as good as that ordinarily provided. Cotton was unsafe to use as Khonkan’s asepsis was so imperfect.

Operations performed at Khonkan were similar to those done in the days of Nelson and Wellington except Coates provided patients the added advantage of pain relief with the use of anaesthetic.

It was ‘field surgery without modern frills’ wrote Coates – ever grateful for the thorough grounding he received as a student from pioneers Hamilton, Russell and Lister.

Coates removed 120 legs.

—————–

Above: Statue of Albert Coates at Ballarat as he appeared at POW Camps, Burma and Thailand

In December 1943, the Japanese Commander Colonel Nagamoto informed Lt-Col Coates the 55 km camp would close (the railway was completed in October 1943) – patients and staff were to be moved to Tamarkan, Thailand. This transfer of patients would be by train. Nagamoto assured Coates they were going to a ‘hospital’ with better food and medical supplies!

The sick were divided into two groups. The Japanese classification – light sick and serious sick. Light sick was a term to describe men who would not die immediately – but men with disease from which they may recover or kill them within 3-4 months. The sick were transported by box truck to near Bangkok. The so-called light sick to Kanchanaburi and heavy sick to Nakompaton.

For the sick men the train journey to Tamarkan was one of terror. There were insufficient stretchers for the large numbers of very ill men. Many had to reach the train stop on foot, hobbling and resting when they could. They would wait hours and hours for a train to arrive. Guards crammed too many men into tiny steel boxes which usually transported freight – some on stretchers, some men stood, some squatted amongst those on stretchers all carrying their possessions –which by now amounted to very little or nothing. Dysentery cases created their own hideous odour, which mixed with the putrid smell of the rotting flesh of ulcers. There were cries of pain with every jolt of movement as the train rode over the uneven levels of rail tracks built by slave labour. On one journey each steel carriage was provided one bucket of raw turnips and one with water (for upwards of 20 men).

There were cries of pain and soon cries for water. The carriages were buffeted about, shunted backwards and forwards at certain stages – for three days.

55 Kilo Camp closed down on 24 December 1943. Dr Albert Coates was then appointed Senior Medical Officer at Nakompaton Camp.

The first group of patients arrived soon after Coates. 1,000 men and within three months the camp held 8,000 – the residual heavy sick from the whole of the Burma-Thai railway with the exception of F and H Force who had been returned to Singapore.

It was acknowledged that 30 Kilo and 55 Kilo camps were the bad ones to be in. 30 Kilo Camp had 2000 ‘light sick’ just herded in there. Tanbaya 50 Kilo Camp was the F hospital camp on the Line – it was also a ‘death’ camp.

For those interested to read of further medical accomplishments at 55 Kilo Camp we suggest reading “The Albert Coates Story” The Will that Found the Way by Albert Coates and Newman Rosenthal, published by Hyland House Melbourne.

RAY WILSON WX8013 worked as an orderly 6 July 1943 as did WX16332 Jim LIND

Men of 2/4th from ‘A’ Force Burma, Green Force No. 3 Btn who died at Khonkan 55 km Camp included:

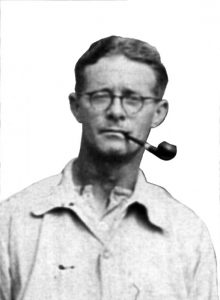

WX17737 Moher, Kenneth (Photo above) d. 24 July 1943 amoebic dysentery aged 28 years. Buried Grave No. 27 Khonkan

WX7022 Hope, Edwin James d. 8 August 1943 beri beri aged 23 years. Buried Grave No. 43. (Photo below on right)

WX5050 Briggs, John Arthur (above Left ) d. 11 Aug 1943 post leg amputation aged 29 years. Buried Grave No. 136 Khonkan.

WX7504 Chapman, Desmond Bruce d. 11 Aug 1943 tropical ulcer, malaria and dysentery aged 27 years, buried Grave No. 130 Khonkan. (Photo below)

WX7625 Clarke, James Sydney (photo above) d. 13 Aug 1943 pellagra and cardiac failure aged 25 years. Buried Grave No. 44 Khonkan.

WX9358 ROBERTS, William Charles ‘Charlie’ d. 16 Aug 1943 of cardiac failure following bacillary desentry. Charlie had been evacuated from Aunggang 105 km Camp 1 June 1943. A farmer from Ravensthorpe he was 35 years of age.

WX8798 Biggs, Guy Percival

(Photo Right)

d. 21 Aug 1943 cardiac

beri beri, dysentery and

tropical ulcers aged 39

yrs. (buried Grave No. 61)

WX7804 Davison, Thomas Medland

d. 5 Oct 1943 chronic.

diarrhoea and malnutrition

aged 34 years.

(Colonel Albert Coates

performed amputation

above leg knee due

to tropical ulcer

4 Jul 1943. Davison was

transferred to Khonkan

55 km Camp.) (buried

Grave No. 204 Khonkan)

WX9231 HODGSON, Leonard Sydney (Tim)

d. 24 Sep 1943 Post leg

amputation and toxaemia

aged 24 years (this was

the second amputation

as the first was below

his knee and the second

above his knee).

WX9214 Lee, John (aka George Lee) d. 26 Aug 1943 cardiac beri beri aged 36 years. John Lee was evacuated from Augganaung 105 km Camp to Khonkan Hospital Camp 28 May 1943. Buried Grave No 87 Khonkan. (Photo below)

WX10388 Meads Kenneth Lawrance. 14 Sep 1943 toxaemia aged 38 years. Ken Meads was evacuated from Augganaung 105 km Camp about 10 Sep 1943 due to tropical ulcers to his right foot. His right leg was amputated above knee but he died post leg amputation as result of toxaemia. Buried Grave No. 139. (Photo below).

Please read further about Khonkan 55 Hospital Camp

55 km Hospital Camp written by Albert Coates

Coates was carried into a hut which was to become his HQ for the coming months two weeks after this camp had been opened 1 June 1943 by Major Charles O’Brien as administrative officer and Lt. W.W. Tilney as adjutant.

55km was a jungle camp with a series of huts originally provided for railway workers with attap huts with bamboo platforms with no bedding at all.

Rations were very scanty with the Japanese regularly weighing every man to determine the total weight. Allowing 1,200 units of rice for each man they calculated to total amount required. Many sick were unable to eat resulting in their weight reduction and an overall much less weight. The Japanese had to provide less and less in rations.

2,000 men shared between them one yak (as small as a calf) killed every day. The bones and body made into soup so that a little was available to pour over every man’s rice – there was no meat left. Coates wrote 55km rations were abominable. He did make a point about the rations to a visiting Japanese General and they did improve somewhat.

Charles O’Brien and Dutch Lt. Col Gottschell were administrators of the camp – organising camp chores, etc. The Australian cooks improved their rice cooking skills.

The Japanese continued to send recent sick men from the railway to 55km rather than to base hospital camps where there were larger supplies of medicines. The sick were transferred by trucks as they were unable to walk.

Capt J. Hggins was the only doctor at 55 km and for the first two weeks while Coates was carried around on his stretcher. Higgins was worried because some men with penetrating ulcers were dying of haemorrhage. (The ulcerating process eating into the main artery and the patients bleeding to death.). Coates quickly realised amputation was the only way to save lives.

Fortunately a Dutch chemist arrived at 55 km and Coates still had a some cocaine tablets which he asked Captain van Boxtel to prepare for a spinal injection enabling Coates to provide anaesthesia below the groin for his first amputation. Following this success 120 amputations were undertaken. Many toes were removed with scissors only.

Coates and his assistants went on to make ligatures of catgut from the peritoneal coat of the intestine of the yak and developed a skin steriliser from alcohol prepared by van Boxtel from Burmese brandy and waste rice.

Coates wrote he believed some of the best work he ever did in his life was accomplished in the primitive jungle hospital camps of Burma and Thailand.

It is of great interest to know the amputation operations performed were similar to those done in the days of Nelson and Wellington with the added advantage in some cases, of a pain relieving anaesthetic.

The following excepts are taken from an address Albert Coates gave in Melbourne 1946.