Since this story was published – we have received information from the family of one of ‘the eight English officers’ who were on the same boat with Bennett departing Singapore on the night of 15-16 February 1942

Please read the information from Francis George Charlesworth

Bennett’s route of Escape

Henry Gordon Bennett was the most controversial Australian General of World War II, chiefly because of his dramatic escape from Singapore in 1942.

Controversy continues today about whether Bennett should or should not have left his troops in Singapore and escape back to Australia.

Bennett believed he did the right thing and declared he would have done it again had the occasion arisen.

He enlisted WW1 and at Gallipoli and in France, Bennett gained the reputation of being a fearless frontline soldier, though a peppery commander who liked to have his own way.

Bennett openly held contempt for the diehard professional soldiers and said all top command posts should be given to Militia officers – of course he was one.

Bennett’s chief creed was: Attack is the best method of defence. Criticising the “Maginot Line complex, he wrote, “Any line can be turned.”

At the outbreak of war in September, 1939, Bennett was the senior Major-General in the Australian Army had confidently expected an important command, if not that of Commander-in-Chief. But he was overlooked on several occasions until he was appointed CO of 8th Division which was formed in 1940.

In Malaya Bennett was again at loggerheads with professional soldiers from Britain and India’s armies.

He was considered bitter, sarcastic, he held grudges and was usually difficult. He often verged on paranoia saying they were all against him, hiding things from him and going behind his back.

Of course there were too many chiefs with fancy titles of importance at Malaya Command (known as ‘confusion castle’) at the best of times without Bennett and his antics. Percival was hampered by a directive from London, giving autonomy to Sir Shenton Thomas specifically stating that no requirement by the military commander must be allowed to interfere with civilian requirements, in particular the production of tin and rubber. First and foremost amongst other issues, Malaya had to provide American dollars for the war effort.

Sir Shenton Thomas was the last governor and Commander-in-Chief of the Straits Settlements and High Commissioner of the Federated Malay States.

On arrival in Malaya Bennett could have developed an efficient working and harmonious relationship with his senior staff, but failed to do so. One good thing Bennett achieved was to abolish the siesta period between 1400- 1600 hours something which every European, military and civilians alike, enjoyed every day. Malaya Command were disapproving and most of the European population thought we Australians were crazy.

Initially Bennett received praise on his arrival back in Australia. But it was soon apparent that there was a strong undercurrent of feeling against Bennett elsewhere, especially in higher Army circles.

‘It was held that no commander should leave his troops in such circumstances.’

At the very least Bennett should have sought permission to leave (his post) from his commander, General Percival and from General Sturdee, the Chief of the General Staff who appointed Bennett to command the 8th Australian Division.

On the morning of the day he left Singapore, Bennett had issued an order stating that all officers in command of troops would stay with their men. A few hours later he escaped.

Percival was not aware of Bennett’s departure until the next morning. Bennett, as commander of Australian forces, should have been with Percival at the Surrender.

__________

Although only 54 years old, it was felt he was not up to this task physically, after an extensive medical examination Alf Derham, the 8th Division’s senior medical officer observed:

‘he is not robust even for his age, gets overtired easily, and seems to feel the effects of the strain unduly. It is my opinion as a medical officer that he is too old for active service in the field and that he would not stand the strain of operations for more than a few weeks at most.’

According to Bennett’s Chief of Staff Colonel Jim Thyer:

‘Between the wars he was a civilian and did not study military tactics, but rested on his World War I laurels. He was moved by hunches and believed in the stars. He was tremendously ambitious and had his head in the clouds, which is the last place a good battle commander’s head should be.’

_________

Bennett always said he would not be taken prisoner of the Japanese. He said “They wont get me”.

There are several versions of Bennett’s escape route. There was plenty of room for details to change –

a) transferring news and stories by telegraph

b) reporters interviewed various persons

Below: This news was sent from Batavia, and printed in the Sydney Daily Telegraph 26 February 1942. In the sixth paragraph the journalist wrote Bennett & his party left after Singapore fell – this is incorrect, Bennett and group left their office the night Singapore fell, leaving his support staff to inform the Battalion and dispose of any official papers left behind.

Bennett’s departure had obviously been planned several days earlier. Initially he planned to go to Burma via Malacca. With two of his officers Lt Gordon Walker and Capt. Charles Moses and a Chinese guide who took them through Japanese lines across Johore Strait to Jahore Barat where their guide John had a friend who would take them to Sumatra in his boat. On reaching John’s friend’s house in Malaya they found it reduced to rubble.

The three men and their guide looked for a boat.

Capt Gordon Walker swam out to a group of boats and guided a sanpan back to the shore which they climbed into. They came across a large ocean-going junk with six British officers aboard who had also escaped from Singapore. They had paid the captain of the junk $100-00 before being invited aboard.

Their chart for navigation was a torn page from a school atlas showing south west pacific with ratio of 230m miles to the inch.

They reached Sumatra in four days having shared very limited rations of water and food. The junk’s captain refused to take them any further, but fortunate as they were, a RAF launch picked them up and they began a journey down the sumatran coast to Java. Major-General Bennett however, managed to continue his journey to Batavia separately by flying boat.

At this point Bennett was in Batavia.

Australia’s Army Minister Mr Forde had no confirmation of Bennett’s escape. He sent an urgent cable to Dutch Commander -in-Chief General Ter Poorten in Java for confirmation.

We know Bennett did not contact Ter Poorten.

The Australian Army had no idea of this news and Mr Forde was hopeful of hearing from Ter Poorten in the morning.

This is another version of Bennett’s escape.

At Singapore Bennett who had escaped two hours after Surrender with Lt Gordon Walker and Capt Charles Moses with a Chinese Guide stole a sanpan which Capt Walker had swam out for.

They rowed out to the strait where they found a junk loaded with British officers and loaded with anti-aircraft shells.The junk slipped past Blakang Mati and continued southwards for five days. Capt Walker said ‘Everyone suffered badly with nerves and wanted to ‘run’ the boat. It was hell! (we can imagine). After 24 hours the escapees began to eat and were rationed to one cup of water each daily. Rations included a handful of rice and carefully divided cubes of pineapple with some bully beef.

From the junk, Bennett and party transferred to a ‘Tern’ a 30 foot police launch previously used in Singapore Harbour which they had seen and hailed. By this time there were up to 19 escapees on board. They sailed through to Sumatra by way of Sambi, Muaratebo (believed northern Sumatra) to Padang and to Java.

Another source wrote ‘they they came across a larger boat, a twakaw loaded with ammunition with three crew and 2 British officers.They paid the owner $150-00 to take them to Sumatra’ . By this time there were 19 men aboard the twakaw.

On 21 Feb Bennett and three companions had seen and hailed a ‘Tern’ – a former Singapore Harbour launch. Those remaining in the tongkan arrived at Rengat. There were now 21 people in the Tern. On the same evening of 21st Bennett left the Tern at Djbami and was provided with a land pass by a Dutch official.

On 24th Bennett was at Padang (Sumatra) where he met up with Brigadier Paris of 12th Indian Brigade. During the evening Bennett had a telephone conversation with General Wavell and discussed the stragglers and deserters at Singapore during last days before capitulation! (of course he was not a deserter!).

The next morning 25th Feb, Bennett took a catalina to Batavia where he was driven to Bandeong. The next day Bennett went to the Port of Tjilatjup with a party of British officers and a wife of one of them. On the 27th, at dawn Bennett was flown out to Broome.

Major-General Bennett failed to inform anybody of his intended departure. What are your thoughts about the subject topic Bennett shared with Wavell? Stragglers and deserters! Wavell blamed the Australians.

The term ‘bumboat’ refers to the ‘tongkang’ and ‘twakow’ lighters that transported cargoes between the banks of the Singapore River and ships anchored in the harbour. Tongkang crewed by Indian and Chinese lightermen were the main cargo-carrying craft used along the river up to 1900, when Chinese-manned twakow began to dominate the lighter business. Both types of vessels were initially propelled using oars and punt poles before the introduction of sail in the 1860s and motor engines in the 1930s. The tongkang’s appearance took after that of craft found in South India, which had a rounded hull and double-ended bow. On the other hand, the twakow was influenced by traditional Chinese nautical designs, with the squat-looking craft having a wide hull with an almost flat bottom designed for carrying heavy loads in shallow waters. Following the river cleanup campaign in 1983, bumboats are now a rare sight and the remaining few have mostly been converted into leisure craft for sightseeing tourists.

Above: Sanpan

https://www.roots.gov.sg/Collection-Landing/listing/1109499

Below: From The Argus, Melbourne 27 Feb 1942

Below: From Canberra Times, 28 Feb 1942

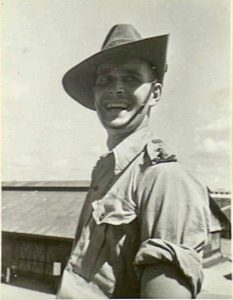

Informal portrait of Lieutenant Gordon Walker of 22nd Brigade, 8th Division, shortly after disembarking from the troop transport Queen Mary on arrival at Singapore.

Below: Capt Charles Moses NX12404.

Upon Percival’s capitulation in 1942, Australian General Gordon Bennett abandoned his command, escaping by boat and taking several key staff officers with him, ostensibly to advise the military hierarchy how to defeat the Japanese.

Among the key staff who escaped with Bennett was 1918 RMC Sandhurst graduate Major Charles Moses. Moses volunteered for service with the Second Australian Imperial Force (AIF) on 13 May 1940, and was given the AIF service number NX12404. A lieutenant in the British Army Reserve of Officers, he was commissioned in the AIF as a lieutenant on 17 May 1940. He was promoted to captain on 1 July, and was posted to the 2/20th Battalion as a company commander. On 3 February 1941, he embarked for Singapore on the ocean liner RMS Queen Mary. He was promoted to major on 24 August 1941, and on 30 August joined the staff of AIF Malaya, under Major General Gordon Bennett.

The General Manager, Australian Broadcasting Commission, NX12404 Lieutenant Colonel Charles Joseph Alfred Moses, (at centre) with members of staff of “9PA”, the Australian Broadcasting Commission’s New Guinea Regional Station in Port Moresby. Other identified personnel, from left to right, are: Mr S.H. Witt, Supervising Engineer (Research), Postmaster General’s Department, Captain E.L. Tidwell, United States Army, Field Supervisor of Radio, Mr C.G. Elworthy, Engineer-in-Charge of Installation, and NX80417 Captain Colin Robin Wood, Manager and Station Supervisor.

Please read the Bennett enquiry and Australia’s views on Bennett