Tamarkan, Tha Makham 56.20km - Thailand

Tha Makham 56.20km – Thailand

Kanchanaburi is 5 km south of Tha Makham.

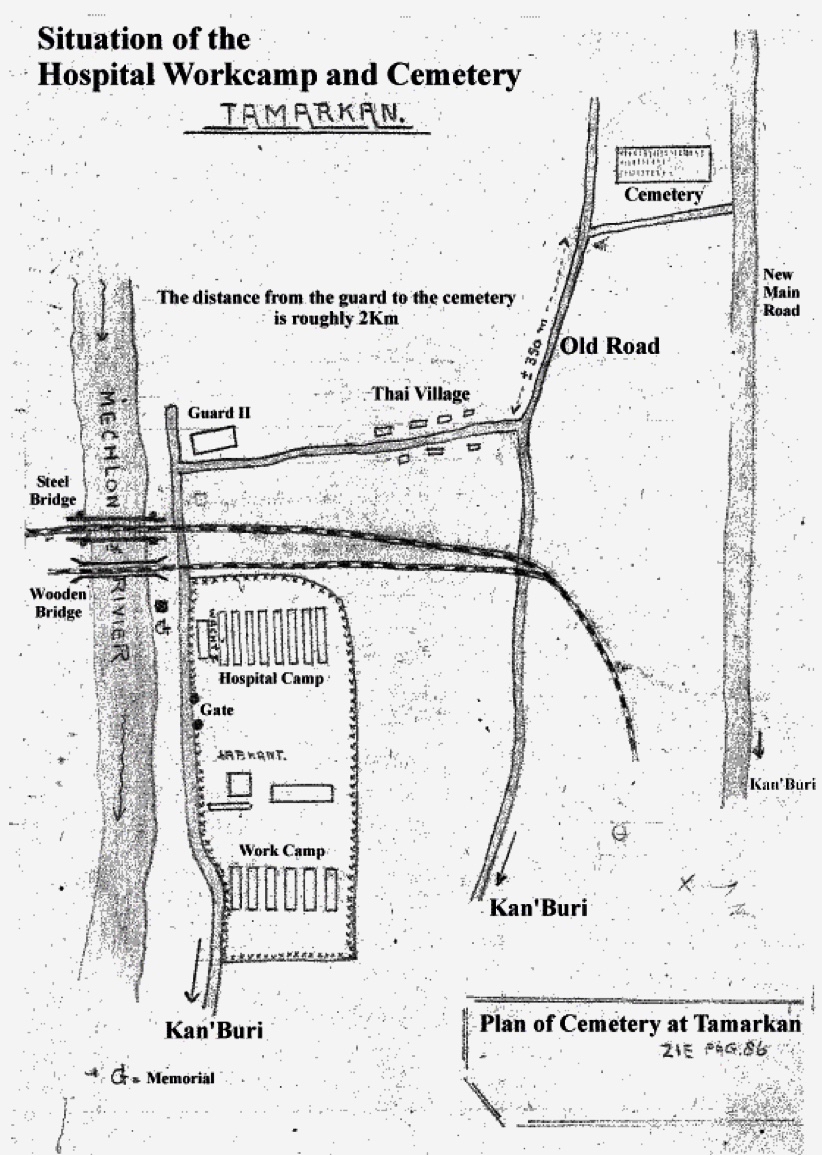

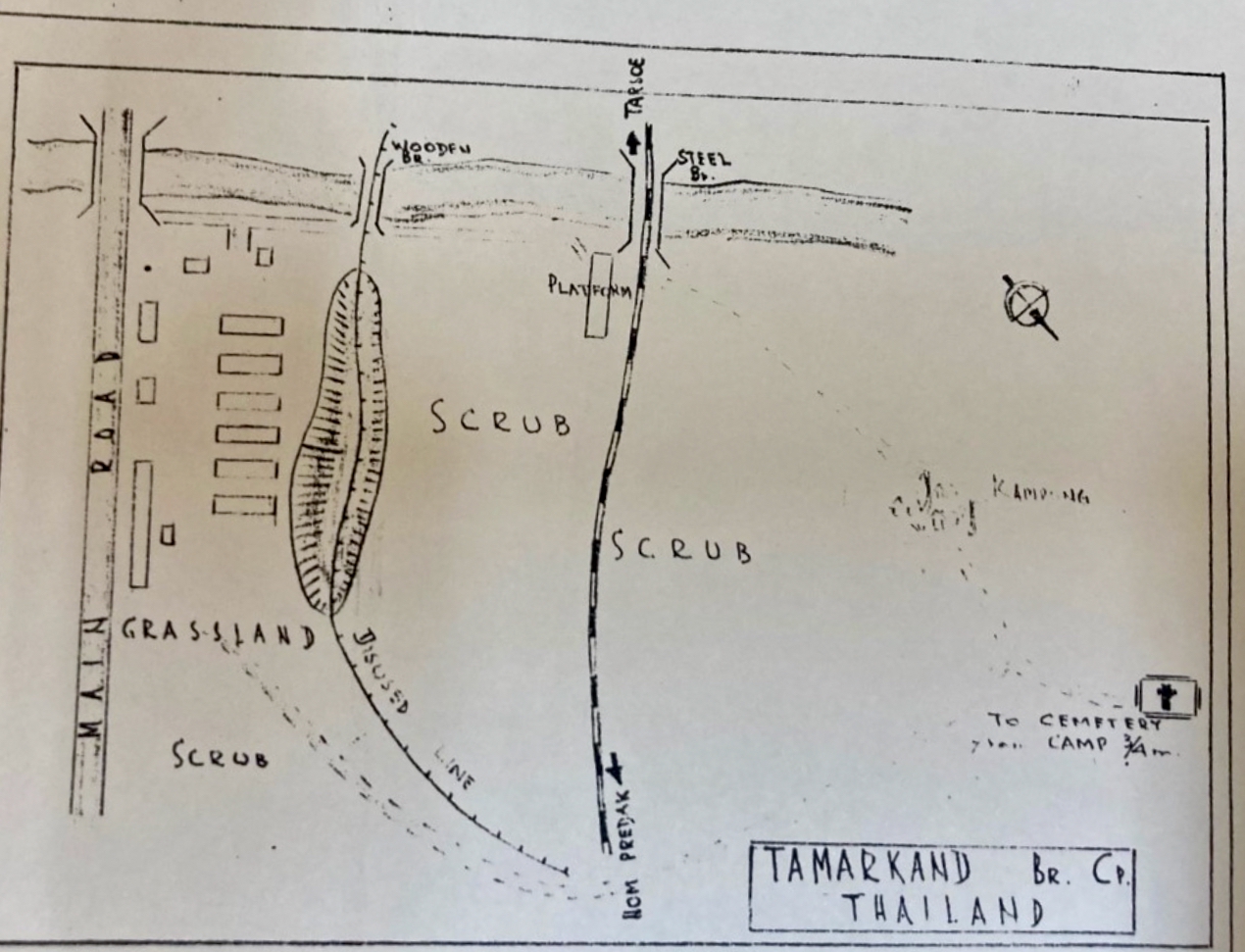

Tha Camp is located on the east side of the River and near to the railway. This is the reason POW Camps were destroyed and POW lives lost when the Allied Bombs raids took place.

Tha Makham was initially a work camp. Commencing 26 October 1942 under Colonel Phillip Toosey British & Dutch POWs built two bridges a wooden one and a steel one across the River Kwai (Kwae Yai).

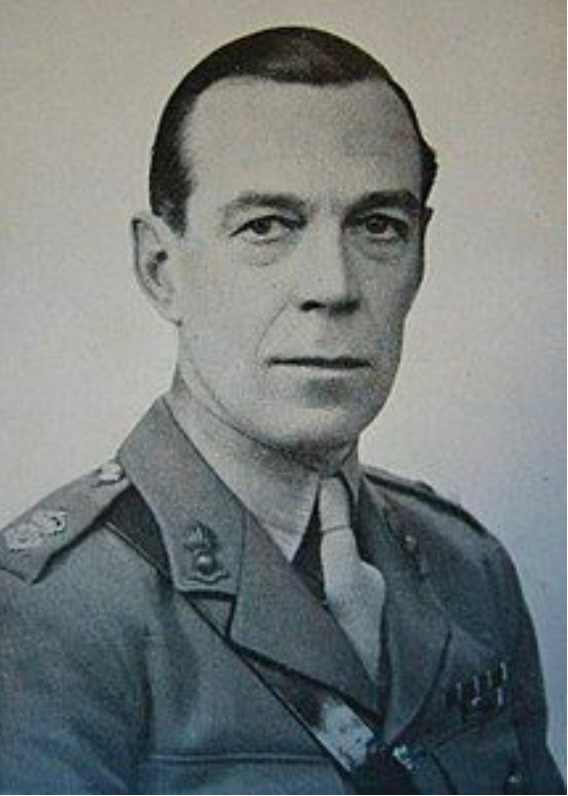

Above: Lt Col Phillip Toosey. Read further ***

Then towards the end of 1943 – The Japanese began bringing large numbers of POWs began arriving from Burma to one of the large camps or hospitals in Thailand. This large number of POWs included ‘A’ Force. Amongst them were the ill and dying – the train journey taking three days.

The very ill remained hospitalised in Burma – the medical staff nursing them in their final days, Every man who could walk out of the camps did so.

Tamarkan is the site of the “Bridge on the River Kwai” and although the original bridge did not survive Allied bombing, the Thai and Japanese Governments together, rebuilt the existing River Kwai Bridge which today draws tourists from all around the world and great numbers of Thai visitors.

The course of the original railway continues to operate to Nan Tok Station. A train ride attracts large numbers of tourists on its 3 trips per day journey.

Tamarkan Convalescent Camp

It was early December 1943 when Brigadier General Arthur Varley and the first remnants of A Force from Burma arrived at their designated convalescent camp in Tamarkan, Thailand, after a long journey by rail. As their train traversed the wooden bridges and viaducts built by their counterparts, they passed the construction camps where the POWs in Thailand anxiously awaited their own redeployment back to base camps. When they entered Tamarkan, they found a well-ordered camp with a lean-to theatre left by the previous occupants.

Tha Makhan was “the bridge camp”—(Tha means pier or landing point) the one made famous by David Lean’s lm The Bridge on the River Kwai, based on the novel by Pierre Boulle.i There were, in fact, two bridges built at Tha Makham: first a wooden one for pedestrian and motor vehicle tra c that served as a temporary railway trace until the permanent concrete and steel railway bridge could be completed just upriver of it. These bridges crossed the River Kwai only in Boulle’s imagination. The river they actually crossed was the Mae Khlong.

Tha Makham camp was established early in October 1942 by British POWs under the command of Philip Toosey, a British lieutenant-colonel in the Territorial Army. Immediately upon arrival, Toosey was ordered to have his troops start construction of two bridges over the Mae Khlong. Knowing that to resist would be futile if not fatal for his men, he obeyed.

With the POWs’ time and energy focused on bridge construction, only a few impromptu entertainments were performed in Tha Makham during late 1942 and early 1943. In February 1943, a thousand Netherlands East Indies POWs arrived to supplement the British labor force, and the wooden bridge was completed later that month.

As the steel bridge neared completion under the newly imposed “Speedo” regimen, Toosey reported that “the majority of the fit men were moved further up the line for more work.”1 Tamarkan was then converted into a hospital camp, where heavy sick from up country work sites could receive better medical care, be rehabilitated, and then be sent back up the line to work. The rest of these seriously ill POWs to arrive in Tha Makham were not Toosey’s own troops but from Groups II and IV who were kept overnight and then passed on to their base hospital camp at Chungkai across the river. Jack Chalker was one of the heavy sick in these groups.

By May, the steel bridge had been completed. Now that the I. J. A. and their POW workers at Tamarkan were “relieved from the unbearable pressure” of their “Speedo” deadlines, the attitude and behavior of the Japanese toward the POWs changed from one of extreme harsh discipline to one of near amiability.

“Concerts took place once a week,” John Cosford observed, noting the change. “After the hopeless, dispiriting experience of disease and death, the comparative cheerfulness was a great tonic to us.”

When the desperately ill among Toosey’s own troops—those sent up the line on work crews earlier—began arriving back at Tamarkan. He was shocked by their condition:

As a typical example I can remember one man who was so thin that he could be lifted easily in one arm. His hair was growing down his back and was full of maggots; his clothing consisted of a ragged pair of shorts soaked with dysentery excreta; he was lousy and covered with flies all the time. He was so weak that he was unable to lift his hand to brush away the flies which were clustered on his eyes, and on the sore places of his body.

One of Colonel Toosey’s goals as POW commandant at Tha Makham was to foster an atmosphere of “equality” between the officers and other ranks in his camp. To encourage this camaraderie, he refused to allow a separate officers’ mess and had all men eat together—a move not appreciated by officers in the regular army.

In late November, Toosey received orders to evacuate Tha Makham so it could be converted into a convalescent camp for A Force POWs arriving from Burma. Toosey’s heavy sick were sent to the hospital at Chungkai, and he, together with his light sick and t troops, was relocated to the supply depot and maintenance facility at Nong Pladuk, where he would take over command. During these relocations, the “Singapore entertainers” returned to their base camp at Chungkai. There they would rejoin others from the original Mumming Bees troupe.

By the end of November/early December, Tha Makham awaited its new arrivals.

Amongst the POWs arriving at Tamarkan from the Burma end of the rail link, was 2/4th’s ‘Doc’ Claude Anderson. There were two other doctors. Claude had three huts filled with patients. He was present when Tamarkan was bombed by the Allies who were intending to bomb the bridge, but many bombs fell on the hospital. 39 Allied patients were killed.

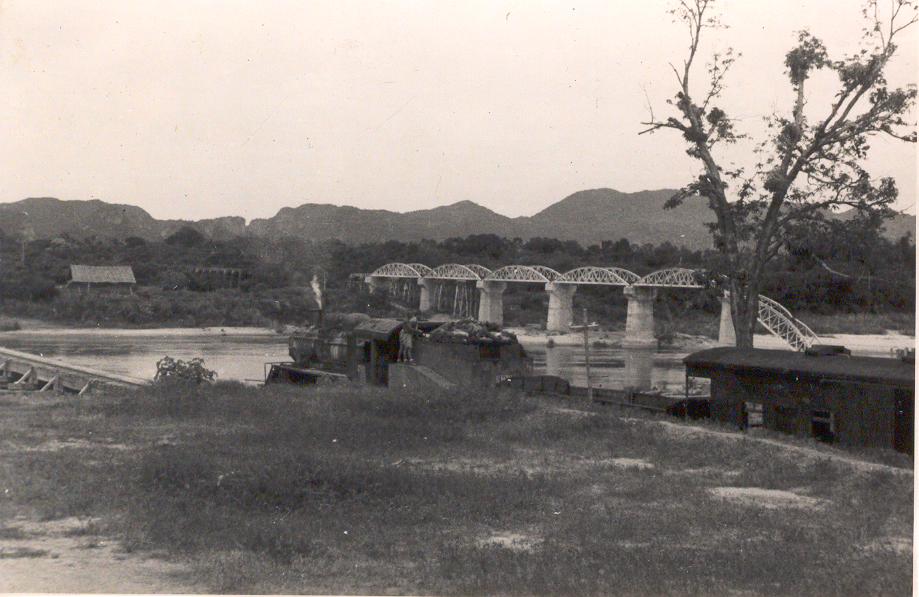

Photograph of the bridges over Khwae Mae Khlong taken adjacent to Tha Makham POW Camp – Steel bridge lies derelict in the background. Photo courtesy of unknown British engineer post war.

Tha Makham No. 2 Hospital Camp

This was one of 3 base Hospital Camps at the southern end of the railway and opened in May 1943.

The camp was 60 yards from the bridge of eleven steel spans and a large AA position. The camp was surrounded by observation post, Japanese engineers, cavalry camp and the railway line. The camp was surrounded by targets for Allied bombing raids! On 29 November 1944, 21 planes bombed the area and 4 dropped on the camp killing 18 POWs and wounding 37.

There were further Allied raids during December. The wooden bridge was destroyed and repaired by POWs.

The POW Camp Commanders complained continually to the Japanese to no avail to have the men moved to safer Camp sites.

The main steel bridge was bombed several times causing considerable damage.

By March 1944 the majority of POWs were brought out of the jungle work camps and so-called hospital camps (these camps were without medical supplies and equipment) and the men were concentrated in the main camps at Nacompaton, Non Pladuk, Tamuang, Kanchanaburi, Tamarkan and Chungkai.

Large numbers of POWs had arrived during the previous months – the Japanese wanted to build up the strength of the men in preparation for selection of work parties for Japan. POWs for work parties for Japan were selected from Tamarkan.

Tamarkan was considered one of the better camps it was well run by a British Officer Col. Phillip Toosey and was well provided by a secretive Thai network of business men, expats and others as well as bankers all of whom risked their lives and those of the families.

On 23 May 1944 was the first time Red Cross parcels were passed onto the prisoners – 6 men to one parcel! For many POWS their first mail was received at Tamarkan on 28th May 1944.

On one occasion two officers and six other ranks escaped from the camp into the jungle. This caused a terrible scene and Saito, second-in-command at the camp knew that the deeply-feared Kempei Tai (the equivalent of the Gestapo) would be called in to investigate. Toosey realised the implications of this so took responsibility for the men’s escape. He told Saito he and he alone had known of their intentions to run away (they were later all caught by the Japanese and executed). Saito beat him severely and ordered him to stand to attention for 24 hours in the full heat of the sun, badly knocked about. It was a public punishment intended to humiliate him in front of his own men but it was also for the benefit of the Kempi Tai who would not feel the need to investigate further, thus sparing the camp a much worse fate. Through this and various other contretemps, Saito and Toosey developed a mutual respect and understanding.

At the end of the war Toosey was called to screen camp commanders for war crimes. It was here that he came face to face with Saito for the last time. To the guard’s intense surprise Toosey shook him by the hand and told him he was free to go. In his opinion, Saito had treated the POWs firmly but fairly. Thirty years later Saito wrote to him: ‘I especially remember in 1945 when the war ended and when our situations were completely reversed. I was gravely shocked and delighted when you came to shake me by the hand as only the day before you were prisoner. You exchanged friendly words with me and I discovered what a great man you were. You are the type of man who is a real bridge over the battlefield.’

67% of all deaths at Tamarkan in 1943 were from bacillary dysentery.

Above information is from

QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, Volume 111, Issue 12, December 2018, Pages 845–847, https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy026

Published: 05 February 2018

‘A’ Force sick begin arriving from Burma to Tha Makham December 1943

For the sick who arrived on train after travelling 3 days from 55km camp Tha Makham was sanctuary. The journey was a nightmare and they were hungry, thirsty and dying.

Brigadier Varley was quartered at Tha Makham. He made tremendous efforts to better conditions for his ‘A’ Force men for whom he was responsible. The Japanese adhered to ‘sick mans do not eat’ policy and Varley fought tirelessly.

Those men of 2/4th who died at Tha Makham Hospital whilst Toosey was in charge included:

WX8870 GITTOS, Thomas Edwin of ‘D’ Force S Battalion died post leg amputation and dysentery 25 Sept 1943 aged 23 years. Below: Gittos on Right

WX8007 KING, Edric Herbert of ‘D’ Force S Battalion died 12 November 1943 of pulmonary tuberculosis aged 32 years.

2/4th who died at Tha Makham Hospital Camp:

WX8855 Davies, David John died cerebral malaria 10 July 1944 aged 37 years. Davies was AWOL at Fremantle and sailed to Java, joined ‘Blackforce’. Left Java with ‘A’ Force Burma, Java Party No. 4 Williams Force. He departed 133 km Camp and arrived Kanchanaburi 13 Jan 1944.

Davies had been selected ‘fit’ by Japanese to work in Japan. Marched out with Party on 27 June 1944, however returned sick on 5 July 1944.

His funeral was conducted by Chaplain F.C. Corry of 2/4th MGB, assisted by Lt-Col Green and Lt. C. Blakeway.

WX6071 Willacott Leslie George (aka Leslie George Willacott Williams) with Green Force he was evacuated to Tamarkan.

He died 7 Feb 1944 of malaria and dysentery aged 36 years. His Grave No G28. Whilst at Ye Aerodrome, Burma Willacott underwent an appenddix operation on 20 Sept 1942. During the fighting in Singapore he was WIA at Hill 200, Ulu Padan on 12 Feb 1942 and admitted to 2/13th AGH with gunshot wound to his right leg. Discharged to unit on 21 Feb 1942.

WX7429 Yensch, Frederick Bernard (Freddie) d. cerebral malaria on 19 Mar 1944 aged 29 years. He was being entrained between Nikhe and Tha Makham on 18 March 1944 when he drifted into a coma. His Grave No. G2 Tha Makham.

Former shop assistant Freddie enlisted AIF 6 Aug 1940. He later joined HQ Coy. No. 3 Platoon.

————————————————-

By the end of November/early December, Tamarkan awaited its new arrivals.

The Australians Take Charge

Responsibility for providing some sort of Christmas entertainment for the few remaining British and N.E.I. troops and the newly arrived A Force POWs now fell to the Australian entertainers. As the secret radio operators and concert party producers Les Bullock and Bob Skilton were part of Brigadier General Varley’s headquarters contingent, it is very likely these two arranged to put on the pantomime Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in their inherited lean-to theatre. Like So Tite and the Little Twerps—the parody of Snow White performed, coincidentally, across the river at Chungkai for their Christmas—the Tamarkan production was lled, no doubt, with covert allusions to their enslavement by “the dwarfs,” a frequent derisive comment made by the taller Australians on the smaller stature of their captors.

The Burma Entertainers

On New Year’s Day 1944, there were further arrivals of POWs from Burma: members of Ramsay Force, including Norman Carter and the entertainers who had formed part of his concert parties in Burma. Their leader, Lieutenant-Colonel George Ramsay, was designated by General Varley as the officer in charge of the camp.

On 13 January, Major Jim Jacobs arrived in Tamarkan with Anderson Force. The following day, Colonel Ramsay sent for him. “He wanted me to take charge of entertainment for the troops, and to get a concert party under way,” explained Jacobs. “There were nearly three thousand British and Australian and some American troops in camp, and this provided a good field for talent, although at least 25 to 30 per cent of the men were sick in hospital.”

Jacobs would find a “good field” of talent from which to produce his shows. It would include Jim Anderson, Val Ballantyne, Les Bullock, Norman Carter, Pat Fox, Sid “Happy” Marshall, Wally McQueen, “Poodles” Norley, Bob Skilton, Jack Turner, Ted Weller, set designer/scenic artist Frank Brydges, costumer Frank Purtell, and Norman Whittaker with his brass band—and Tony Gerrish with his dance band.

The context in which a play is produced can change everything in terms of an audience’s reception. When Journey’s End was performed back in Changi POW Camp by the 18th Divisional Headquarters Players on the 1st anniversary of their captivity, it had received mixed reviews: their British audience had been moved by it, but their Australian audience—still smarting with deep resentment from their defeat and surrender caused, they believed, by the incompetence of the British military leaders—totally rejected its “message” of solidarity among the ranks and cheered, instead, the appearance of the captured German soldier .

Talented POW entertainers would also be found. This is the first word we have of Tony Gerrish and his dance band, but they may have been the band mentioned by Frank Samethini performing for the “Singapore entertainers,” or, perhaps, they were the musical ensemble that played for Skilton and Bullock’s shows at Thanbyuzayat. Gerrish was an Englishman, and two members of his band were Americans, sailors in the U.S. Navy who were rescued when their ship, the U.S.S. Houston, was torpedoed and sunk. Navy bandmaster G. L. Galyean played the ugelhorn; Petty Officer 3rd Class Wilbur G. Smith played the bass viol, albeit a “jungle style” version made out of a wooden box with a bamboo upright and a single piece of signal wire as a “string.” It could only be plucked, not bowed.

With this collection of producers and performers together in the same camp, extraordinary things were about to take place in the entertainment world at Tamarkan.

Carter Tests the Waters

Jacobs first produced a series of variety shows. When Norman Carter saw them in what he called the “lean-to shack” of a theatre, he thought they were quite poor, evidenced by the fact that they were not drawing audiences. He thought Jacobs an excellent performer but not a skilled producer. From his experience up country, Carter knew that what the POWs badly needed was a different type of entertainment—one with characters and storylines. And they also needed to be excited by the “wow” factor that sets, costumes, makeup, props, and lights could provide.

Carter knew he could offer this type of entertainment and that his recent production of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves at Aungganaung for Christmas would be just the ticket. With the cast and production stage of that pantomime now in Tamarkan, it would easy to remount.

Ali Baba—Carter’s first show in Tamarkan—appeared on the lean-to stage at the end of February.

Once he saw Carter’s production, Jacobs realized he had a talented producer-director on his hands, one who could develop marvellous shows for the camp if given the opportunity and support. He volunteered to get permission from Colonel Ramsay to “pull this cowshed down and build a proper theatre” so Carter could produce revues and musicals for the troops. Carter suggested they should open the new theatre “with a real smasher . . . The Wizard of Oz!”

“The Tamarkan Players”

Colonel Ramsay not only gave Jacobs permission to build a new theatre but nominated the members of a theatre committee to manage it: Jacobs would be officer in charge and general manager, Norman Carter, producer; Lieutenant John M. Vance, secretary; and Padre Keith Mathieson of the H.M.A.S. Perth and Private Val Ballantyne, additional committee members. Ramsay also provided support for the concert party by giving them money from the camp fund so they could purchase needed materials. The new concert party was called “The Tamarkan Players.”

With the array of talented actors, singers, and comedians available to him in Tamarkan—and with the support of the theatre committee and his team of designers and technicians—Carter set to work on a series of monthly spectacular and entertaining productions. In many ways, the story of entertainment in Tamarkan during 1944 is the story of Norman Carter and the extraordinary revues and musicals he produced. Besides his skills at directing actor-singers, Carter was also gifted at enlisting the artistic abilities and skills of designers and technicians to realize his production concepts.

Carter Sets the Standards

Arthur Shakes took responsibility for pulling down “the cowshed” and constructing the new theatre. Carter told him what was needed: “it must have a gabled roof, so that you can see the whole of the back wall, not just a fraction of it. It needs height, so that you can put up a grid from which to hang scenery, and it also needs depth and width, like an old-fashioned barn, some space o -stage for the actors to dress, and a pit for the orchestra.”

The New Tamarkan Theatre

A week after Carter’s discussion with Shakes about the design of the new theatre, it was finished. It had been built opposite the men’s living quarters, facing the parade ground.

The “Rimboe Club” Arrives

In early April, a new contingent of N.E.I. POWs arrived in Tamarkan from Kanburi hospital camp a few miles down the road. In this group was a Dutch/Indonesian cabaret troupe, known as the “Rimboe Club,” who had performed in Regue/100 Kilo, Burma, and more recently in Kanburi. Led by the Dutch adjutant van Dorst, it contained several comedians, singers, and musical groups. In contrast to a like situation at Chungkai that turned into a full-blown contretemps when a Dutch/Indonesian troupe sought permission to perform, the newcomers at Tamarkan were invited to present their shows under the Tamarkan Players banner. The soldier who had danced the Hawaiian hula as “Miss Waikiki” in Regue would become famous in Tamarkan as “Sambal Sue”—a nickname given “her” by the Australians and Americans after the spicy-hot Indonesian finger food available in the camp.

Production Challenges

But producing quality theatre at Tamarkan would not be easy. Part of the difficulty was the fact that the Japanese administration would not allow rehearsals. This restriction was manageable if all that was produced were variety shows that only needed someone to devise the lineup on the playbill and a good compère to keep the show going. But for anyone trying to produce revues and musicals with scenes between characters, dances that needed choreography, and multiple set changes—all of which required careful rehearsal and coordination—it was an impossible situation. At first, Carter tried to operate within the rules. “Those involved in performance of the concerts,” Ted Weller recalled, “would learn their own lines without having a rehearsal. Carter was a strict disciplinarian and would give each performer his part and expect him to be ready for the performance on the night.” But for a perfectionist like Carter, this restriction soon became intolerable.

Therefore, a “legitimate” version of “tossing the doctor”—the term used by the POWs for tricking a medical officer into believing you were so ill you couldn’t work—had to be developed to circumvent the restriction. It wasn’t only the actors and musicians who needed rehearsal time; it was also the design and technical staff. “But with the co-operation of POW medical officers and administration staff ,” Rae Nixon explained, “men who did the set construction, scene painting, music writing, costume making and rehearsing were offcially classified ‘in hospital’ or in [camp] work parties.” In this way, cast members and key production personnel were “kept hidden from work parties,” which allowed the concert party to become “much larger and important for moral support which was obvious in the help and health of the men generally.”

But, as Tom Morris admitted, there were times when even this subterfuge didn’t work:

And you couldn’t always protect those people, you know. If suddenly the Japs wanted a working party, everybody was pulled out on parade and the Korean orderlies [guards] just went around, and, you know, whooshed! And if you happened to be one of the concert party and you couldn’t pull a string, you just went o on a work party somewhere.

In due time the “no rehearsal” policy eased a bit, and rehearsals were permitted—but only according to a very exact schedule.

Rehearsals were particularly awkward to manage as the Japanese stipulated that only one afternoon a week could be used for rehearsals. On that afternoon the order laid down was half an hour for dialogue, half an hour for singing, followed by the string orchestra, and finally the brass band. The order, and the time set for each section, was rigidly supervised by the Japanese. On no account were two sections allowed to rehearse at the same time. Why? No reason. Just Japanese orders.

The Wizard of Oz

Carter’s production of The Wizard of Oz opened in mid-March.

Rae Nixon’s Sketchbook

One of the most remarkable artifacts to survive the ravages of the Thailand-Burma railway is Rae Nixon’s sketchbook, “Jungle Theatre Tamarkan . . . a ‘look-see’ around the wardrobe . . .” produced between April and July 1944.43 Illustrated in full color are costume renderings for three of Carter’s major productions: When Knights Were Bold, Memories of the Gay 90s, and Dingbats Abroad. It also contains color sketches of the Tamarkan theatre, illustrations for wigs and accessories, and one sketch each of Norman Whittaker’s brass band and Tony Gerrish’s dance band.

When Knights Were Bold

Norman Carter’s production for April was the musical comedy When Knights Were Bold. Having performed in a production of this popular West End musical in England, Carter wrote the whole script from memory.

There followed construction of a better theatre, improved productions etc.

‘Men were still having their legs amputated through tropical ulcers and the cheerful way men with one leg hopping around on bamboo made crutches was good to see. One concert night 12 men with only one leg sang songs as ‘Waltzing Matilda,’ ‘Home Sweet Home’ and ‘Roll Out The Barrel.’”

Japan Parties

For months, rumors had circulated in the camp about POWs being sent to Japan. In April those rumors became a reality when fit men were selected, or volunteered, for a series of overseas drafts that would continue into June. Many of the prisoners were tired of living in a boring POW camp in Thailand. They thought conditions might be better in Japan. Two of these men were Jack Turner and his song parody writer mate, Frank Huston. Another was Brigadier General Varley, only in his case he was ordered to leave Tamarkan and join the other senior British and Australian officers who had been removed from Changi to Formosa in 1942. On his departure, Lieutenant-Colonel Anderson took over command at Tamarkan.

The Japan Party drafts were sent by rail to Saigon, French Indochina, for transport to Japan. But they were delayed from sailing because American aircraft and submarines were raiding the Japanese shipping lanes.

Camp Update: “Better Termed a Rest Camp”

At the beginning of May, Major Jacobs took stock: “From the time of our arrival at Tamarkan [in January] the health of the men began to improve. For the first three months the sick from the jungle camps were dying at the rate of ten to fifteen each week. By May 1944 most of the men not in hospital were fairly fit, while the majority of the hospital patients were out of danger.” Arthur Bancroft agreed: “Life here was far from boring and an occasional concert made conditions almost ideal. It would have been better termed a rest camp.” Better food, medicine, light duty, sports—and a constant supply of quality entertainment— had played major roles in the transformation.

Pinocchio

Pinocchio was Norman Carter’s musical production for May.

“Home for Christmas”

__________