Are you surprised Australia had a Camel Corps in WW1?

Do you remember the story of Lawrence of Arabia?

View several of Frank Hurley’s amazing photographs of Australian Imperial Camel Corps WW1

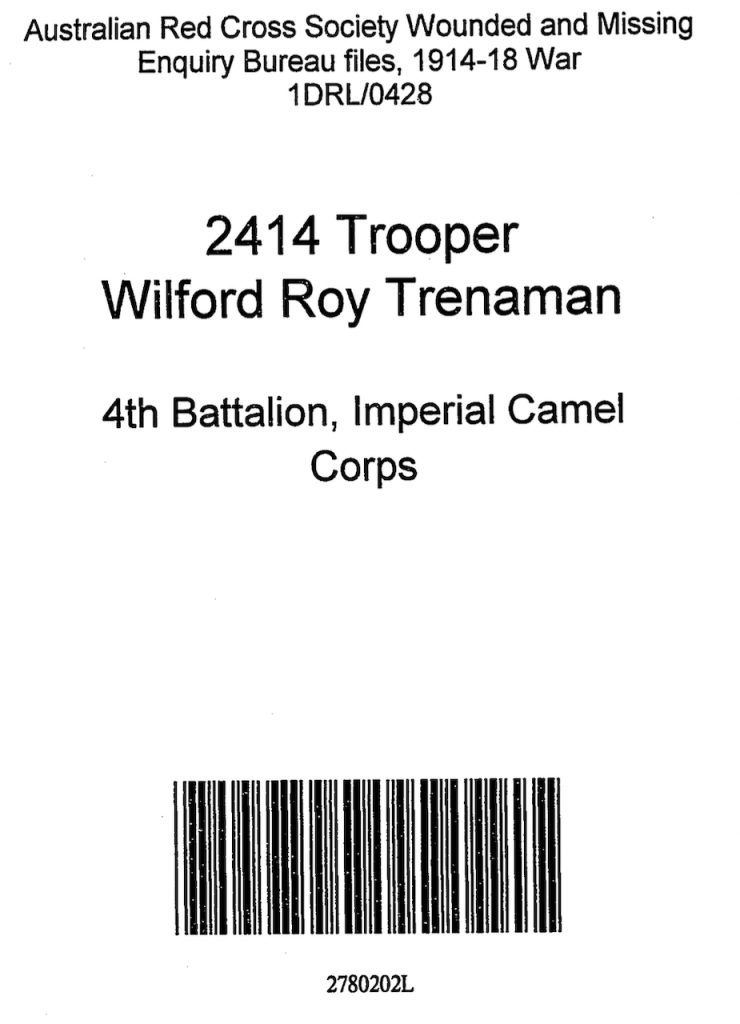

During research for WX9554 Corp. Arthur Lindsay Roy POWELL of 2/4th who survived the war as a POW of Japan – we discovered he was named after his uncle – Trooper Wilfred (Roy) TRENAMAN Service No. 2414, 4th ANZAC Camel Battalion AIF, who enlisted from Nanine however had been working at Barrambie – a goldfields mining ‘Town’.

Trenaman was KIA Palestine 30 March 1918 during operations at the First Battle for Amman, aged 26 years. His name is memorialised at Jerusalem War Cemetery with 3,300 Commonwealth serviceman from Egypt and Palestine with no known grave.

Trenaman enlisted AIF 16 May 1916 first joining 10th Light Horse, embarked HMAT Surada from Fremantle. He transferred to 4 Battalion Imperial Camel Corps (Australia).

Trooper Wilfred (Roy) Trenaman was working at Barrambie when enlisting. 116 kilometres south east of Meekatharra and 75 kilometres north west of Sandstone it was a mining town and somewhat wild!

(We wish to acknowledge and thank Moya Sharp who wrote of Barrambie: put the ‘wild’ in the wild west!!)

‘Half the men were replaced each pay day at the Barrambie Range Mine as they were drunk and not turning up for work.’

I recommend you read about Barrambie

WX9554 Arthur (Lindsay) ‘Lin’ Roy Powell was born Northampton 1918 to Arthur Powell and Clara Evelyn Trenaman. He spent his formative years at Northampton. Known to everybody as ‘Lin’ he enlisted firstly with 11th Battalion Militia prior to enlisting AIF in Dec 1940 aged 22 years. He joined Battalion Headquarters No. 3 Platoon in the role of carpenter. On 24 Jan 1942 he was promoted to Corporal.

Please read about the ‘Boys from Northampton

As a POW in Singapore he worked on Burma-Thai Railway with ‘D’ Force Thailand ‘V’ Battalion, departing Singapore in crowded railway trucks (28 POWs in very small railway trucks) on a 4 day hellish journey bound for Thailand. ‘V’ Battalion under the leadership of 2/4th’s Major Alf Cough endured the toughest working and living conditions of all ‘D’ Force. The loss of life and sickness was tragic and staggeringly high.

Please read about ‘D’ Force ‘V’ Battalion.

Towards end of 1943 the railway line was mostly completed and the Japanese began to move all POWs in camps throughout Burma and Thailand to one of several large Thailand based camps or hospitals – hospitals for the many sick and dying. Food and health care was very much improved compared to ‘speedo’ and those months and months slaving and starving on the Burma-Thai Railway – the Japanese now wanted POWs fit and healthy to send to work in Japan – which at that time extremely short of labour.

Lin Powell was fortunate to avoid selection – he may well have been sick. Those of ‘V’ Battalion who went to Japan endured a hellish ship journey to Moji, Japan to work at Omuta coal mine – run by American POWs where conditions were ruthless and likened to the Mafia.

We believe Powell was sick, possibly evacuated out of the railway at Brankassi Camp possibly to Tamarkan Hospital. Having recovered somewhat, he was selected in a work party to Pratchai. Please read about Pratchai.

Powell was working at Pratchai when the end of war came. He was evacuated to Bangkok to fly to Singapore. He sailed home on the ‘Circassia’ from Singapore to Fremantle at the end of 1945.

Below: Lin Powell’s photo taken about 1940-41 when he was 22 years old.

Please read further about Camel Corp.

The Motto “Nomina Desertis Inscripsimus” – In the Desert We Have Written Our Names.

IMPERIAL CAMEL CORPS (formed with British, Australian, New Zealand & Indian forces)

There existed an urgent need for long-range desert patrols in Egypt. In 1916 the Imperial Camel Corps (ICC) was formed. (The Australian and New Zealand Corps were attached to Anzac Mounted Division). The ICC first fought against the Senoussi on Egypt’s western frontier and then were deployed to the eastern frontier against the Turks.

The Australians and other units in Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) advanced into Ottoman territory. In 1917, the troops entered Palestine. In 1918, EEF advanced into modern-day Jordan and Syria. The campaign ended on 31 October 1918, a few weeks after the capture of Damascus.

The battalions of the ICC fought alongside light horse units at Romani, Magdhaba, Beersheba and Rafa, and remained an integral part of the force that advanced north through Palestine in 1917 and 1918.

Tens of thousands of camels were needed to get water to the soldiers, and they were excellent for desert patrolling. Later, they were also used to transport cameliers into battle – the riders would dismount to fight. And of course the camels were essential to transport wounded and ill troops.

In 1918 when the Camel Corps disbanded, (the terrain in northern Palestine was such that the camels were no longer useful) the men transferred to the Australian Light Horse brigade.

The first five photographs were taken by photographer Hurley.

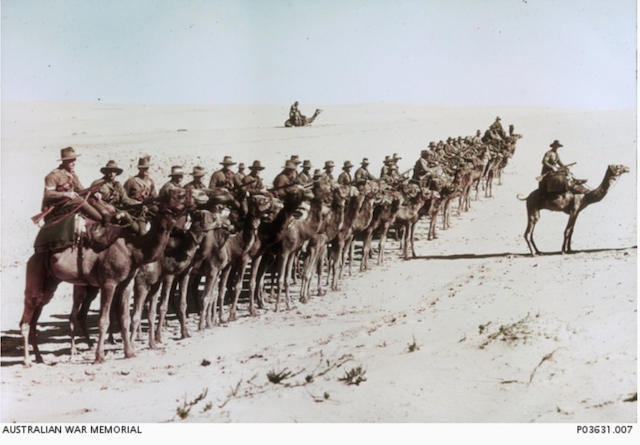

Above: Australians of the Imperial Camel Corps on the march, 1917-1918

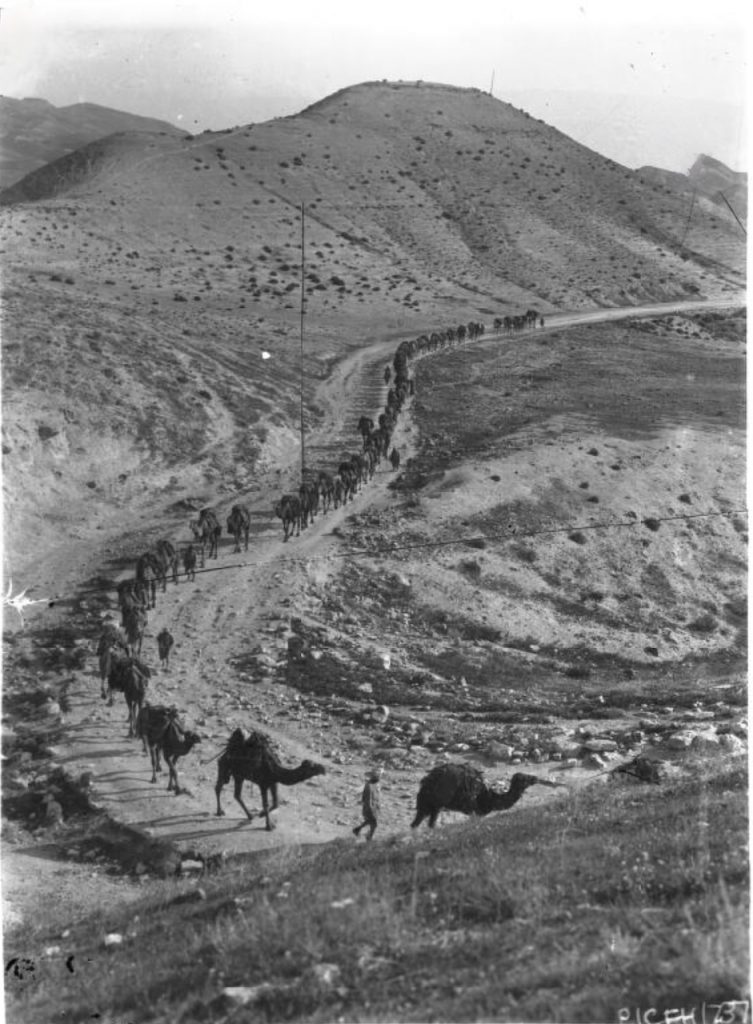

Above: Palestine hills and water.

Above: Camels crossing water.

Above: Rocky, hilly landscape Palestine.

Above: Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives, on lower left Absalom’s Pillar, on right the Grotto of Saint James, Kedron Valley.

Above: Egypt on leave.

Above: Left to Right note the uniforms of the Australian, British, New Zealand and Indian troopers from Camel Corps.

Below: Indian Camel Corps Trooper

Below: Australian Camel Corps

The Imperial Camel Corps Brigade was formed January 1916 from British and Commonwealth troops (Australia, New Zealand, India) and attached to Anzac Mounted Division. There were four regiments: the 1st and 3rd were Australian, the 2nd was British, and the 4th was a mix of New Zealanders and Australians. Each regiment had around 770 men, and at full strength the brigade contained almost 4,000 camels.

Initially the Camel Corp was used to deal with the revolt of pro-Turkish Senussi tribesmen in Egypt’s Western Desert. During 1916 the Camel Corps undertook long patrols and brief skirmishes with the Senussi. British commanders in Egypt appreciated their fighting qualities and in late 1916 the ICC was transferred to the Sinai desert to take part in operations against the Turkish army.

Battalions of the ICC fought alongside Australian light horse units at Romani, Magdhaba and Rafa. The ICC remained an integral part of the British and dominion force that advanced north through Palestine in 1917 and 1918. It suffered particularly heavily during the Second Battle of Gaza on 19 April 1917, and in the operations conducted in November to destroy the Turkish defensive line between Gaza and Beersheba. As the ICC moved into more fertile country of northern Palestine, its practicality declined. The camels needed more fodder and water than equivalent numbers of horses. Unimpeded by the desert, horses could now move much faster.

Fresh supplies from ships came ashore on barges and then travelled by camel to military camps. Camels were used as ambulances, with stretcher-like cacolets attached to their saddles – a terrible and painful ride for injured!

The Camel Corp were involved in conflicts alongside the Light Horse. The cameleers would ride to the scene of action, dismount and fight on foot – as infantrymen. As with the Lighthorse a group of four troops lived and worked together forming a team. During action one trooper/cameleer would remain behind with the camels.

Troopers found camels were a lot easier to control than horses, once they were barraked (made to kneel down). Much less prone to panicking when exposed to enemy artillery and small-arms fire it soon became normal procedure for one man to look after 12 or even 16 camels once they were barraked.

-

The dromedary is a single-humped camel native to the Middle East and North Africa. The larger bikaners were used for carrying. The lighter Egyptian camel, in particular females was preferred for riding.

It is true Camels may be prone to have bad breath and bite. However they can:

-

carry up to 145kg – including cameleer’s equipment and supplies including 300 rounds of .303 inch ammunition for his rifle survive without water for up to 6 days, routinely 5 days, whereas horses required water daily.

-

travel over 40km a day – walking pace was calculated at 4.8 km (3 miles) an hour. At a trot the camel could make 9.5 km (6 miles) and hour.

‘The camel was well adapted to desert conditions, their feet splaying for traction in sand, their stomachs able to retain prodigious quantities of water, they can cover great distances where nothing else could even survive, while also capable of considerable bursts of speed. A modern racing camel can canter as fast as a horse for an hour and more, and sprint at 40mph.’

-

Camels eat almost any green vegetation they can find in the desert.

-

At full frontline strength the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade required approximately 3,880 camels. Sufficient to carry enough supplies and equipment to keep the Brigade in the field for five days as well as providing mounts for the men.

-

The Corps was supported by a Camel Remount Depot and Camel Veterinary Hospital where the camels were well cared for if necessary and returned to service. On a daily basis the troopers cared for their own camels, brushing down their coats and removing ticks. The troopers named their camels. In accordance with local Egyptian practice only un-neutered male camels were used. The following is a description by NZ trooper.

-

‘Sometimes in the syming [rutting] season a bull camel will go mad, and attempt to run amok through the lines, attacking anyone in its path. In this condition the brute lurches straight forward with neck outstretched, bared teeth, and foaming mouth, towards the object of his attack, and blindly stumbles over rope-lines or other obstacles in his path in his attempts to reach his victim. When a camel attacks a man he uses his teeth first, and then attempts to crush the life out of him by kneeling on him and pounding him with his hard horny knees.’

It was said the Carmel Corps ‘were notorious as rough men of less than desirable character’ – apparently they used colourful language i.e. swore a lot! Australian battalion commanders had seized upon the opportunity to offload some of their more difficult characters into the Camel Corps. They were regarded as poor cousins compared to the dashing Light Horse Brigade. The Camel Corps proved themselves to be inventive and effective in battle. The CC suffered terrible losses in the 2nd Battle of Gaza. When they ran out of ammunition, they hurled down rocks onto the Turks. The large numbers of wounded endured agony being transported by the 5th Camel Brigade Field Ambulance – rocking side to side, the journeys were particularly long by which time many wounded were dead.

The most famous camel-rider was world renowned Colonel TE Lawrence – Lawrence of Arabia.

Lawrence explained he wore Arab dress because it was more comfortable than military uniform when astride the beast.

Below: Ottomans completed this railway construction in 1908, to the surprise of many who believed the Ottomans were not capable. Below map shows the route.

One of the reasons for the attack by Camel Corps was to capture the important Hedjaz Railway at Omman in 1918 and thus prevent the movement of Ottoman Troops north and south.

Can you recall those ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ scenes where Lawrence with his dedicated team of arabs seemed to be aways blowing up the rail tracks?

Below: First Raid on Amman – Roy Trenaman was KIA Amman 30 March 1918. On this day, Sat 30/03/1918 – 1,530 died across WW1 battlefields.

‘The first “raid” on Amman was mounted between 22 and 30 March 1918 by the British 60th Infantry Division, the ANZAC Mounted Division and the Imperial Camel Brigade with the intention of inflicting casualties on Turkish forces and severing railway communications with Damascus. The force crossed the Jordan River on 22 March and, despite difficult conditions, the village of Es Salt was occupied by the evening of the 25 March. The attack on Amman itself commenced on the morning of 27 March with the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles and the cameleers providing the attacking force. Fierce fighting continued for two days. The force effected serious damage on the railway but Turkish resistance was so strong that British forces withdrew on 30 March. All elements of the raiding force had recrossed the Jordan by 2 April.’

From AWM

‘Defending Amman on 27 March the Ottoman and German garrison consisted of 2,150 rifles, 70 machine guns and ten guns. Jemal Kuchuk commander, Fourth Army, arrived on 28 March to take command of the defence of Amman. Up to 30 March, approximately 2,000 reinforcements arrived with more to follow. In reserve at the Amman railway station were the 46th Assault Company from the infantry’s 46th Division. Part of the 150th Regiment (48th Division) garrisoned Amman and part of the regiment guarded the railway to the north and south of the city. One battalion of this regiment and one battalion of the 159th Regiment with some Circassian irregular cavalry, guarded the region towards the Jordan River between Es Salt and Ghoraniyeh, manning posts guarding the river. The German 703rd Battalion with a cavalry troop, an artillery section and the Asia Corps’ machine gun company which was “particularly strong in machine guns”, had arrived back from Tafilah and was in the foothills at Shunet Nimrin on the Amman road by 21 March. These units amounted to no more than 1,500 rifles deployed between Amman and the Jordan River, when the EEF crossed the river.’

Total casualties of both infantry and mounted divisions were between 1,200 and 1,348. The 60th (London) Division suffered 476 infantry casualties including 347 wounded and the Anzac Mounted Division (incl. Camel Corp) suffered 724 casualties including 551 wounded.

Above: British 60th Infantry Division – marching to the First Battle of Amman

Procedure for Injured.

-

1. Regimental aid posts – usually set up about 700 yards behind the front.

- 2. Field and Light Horse field ambulances –

Field ambulance staff moved the wounded from the regimental aid post (just behind the front lines) to an advanced dressing station. The trip was about 1 to 3 miles (1.6 to 4.8km) and took around 6 hours to complete.

Stretcher-bearers worked in relays. At least 36 stretcher-bearers handled each patient along the way.

The main dressing station was another 3 to 8 miles (4.8 to 12.9km) beyond the advanced dressing station.

-

3. Casualty clearing stations: Camel cacolets used by the Light Horse Field Ambulance which are used for bringing sick and wounded across the desert to the clearing hospitals, from where they are sent to base hospitals.

- Below: Some evacuated to train sidings.

-

4. Base hospitals:

-

I would imagine many wounded knew they would never reach a base hospital and they were right. ‘The journey’ could take sometimes as long as a week or two.

The regimental aid post was a vital point of liaison with the field ambulance units set up further behind the front. The post controlled everything in front of its position. Field ambulances controlled the medical evacuation chain behind the post.

Above: Hedjaz Railway was essential for transporting supplies, troops in WW1.

The war ended October 1918 and the Imperial Camel Corps was rapidly broken up. At Lawrence’s request many of the camels were given to the Arab forces who had fought alongside Allenby’s men.

“We were sorry for the camels. Although we often cursed them, when they were to be taken away from us we found that we had become quite attached to our ugly, ungainly mounts. The Arabs would not treat them as kindly as we had done, and we reckoned they were entitled to a long spell in country that suited them better than the rough and slippery mountain tracks of Palestine.”

Please listen to the Australians of the Imperial Camel Corps – they also mention personal knowledge of Lawrence.

Below: Camel Corps transporting supplies

Known as Cacolet Camels – Right: for wounded who required to lay down Left: for the wounded who could sit. Understandably and sadly many wounded did not survive the slow and agonising journey to reach medical aid.

Above: Camel lines for the Imperial Camel Corps Field Ambulance.

Above: ‘Barraking’ (made to kneel).

‘Mounted drill began with “barracking” – getting camels to their knees. The rider tugged the halter rope downwards, making a guttural “duh, duh, duh”. Old soldiers were intrigued to find that the camel seemed to do everything by numbers:

One! Bend the lower portions of the forelegs.

Two! Sink down on the lower sections of the hind legs.

Three! Fold the upper portion of the front legs on top of the lower.

Four! Bring down the upper parts of the hind legs above the lower.

Five! Shuffle and tuck in the feet comfortably.

Six! Groan.

On the order “Get read to mount” the rider pulled round the head of the camel until it looked to the rear, placed his left foot on the bend of its neck and grasped with his right hand the peg at the back of the saddle.

On the word “Mount” he raised himself sharply into the saddle, throwing his right leg over the front peg (pommel), let out the halter full length and the camel would instinctively rise to the accompaniment of ferocious roaring that stopped as soon as the camels were up.

On a dark night in a wadi the effect could be weird!’

Below: List for Troopers to take on active service – Marching order. The Dhurra bag was Carmel food.

Above: Midday rest scene. In foreground are ‘fantassies’ (5 gallon water vessels) and dhurra bags (containing 50 lb corn) for camels

We wish to acknowledge the above 3 photographs are from ‘Sand, Sweat and Camels. The Story of the Australian Camel Corps’ by George F and Edmee M Langley. ISBN 0 7270 1013 1.

Above: Australians of the Imperial Camel Corps near Rafah during the war against the Ottoman Empire, 26 January 1918

Note: Troopers above stripped off uniforms, often remaining shirtless in the desert heat – when discovered by an Officer in Egypt quite near to ‘Barracks’ at Cario he complained. Obviously these officers never travelled in the desert and probably never left the comforts of Cairo life. In fact Cario seemed to attract large numbers of officers and government officials who would later be ‘cleared out’ – of no value in a war.

Above: Imperial Camel Corps riding outside Beersheba 1917.

Above: Feeding time.

Above: Bath-time for the troopers and their camels.

We wish to acknowledge Imperial War Museum for these photographs – an opportunity to share these historical insights with today’s Australians.

Above: Ambulances

Above: Amman looking towards the Citadel 1918.

Above: Pencil drawing of Omman in distance.

Above: Amman Raid March 1918

Above: Hill 3039 where we believe Trooper Trenaman lost his life 30 March, 1918. 62 Troops died at Israel/Palestine conflict on this day, it was a military failure. There had been no time to collect and bring back dead troops.

Please read further about Camel Corps

We acknowledge Birtwhistle History Centre, Armadale, WA

Two years of service cost the ICC 240 deaths: 106 British, 84 Australians, 41 New Zealanders, and nine men from India.

Above: CC officer outside his tent. Everything was temporary – to be pulled down and erected elsewhere.

Below: Jerusalem CWG Cemetery

Below: Red Cross Report – Wilfred (Roy) TRENAMAN’S body was never recovered. His name is recorded on the Australian Memorial WW1 – Jerusalem War Cemetery.

Trenaman is one of 3,300 Commonwealth Serviceman who died WW1 in operations in Egypt or Palestine who have no known grave.

It was an unwritten law those serving with Camel Corps and Light Horse were always recovered unless absolutely impossible. The nomadic Bedouin usually robbed bodies of personal effects and sometimes worse. This silent law was also applicable to the Turks and Germans. There are stories of Turks carrying a white flag to return an Australian’s belongings recovered from a Bedouin.

Above: The Imperial Camel Corps Memorial – This sculpture is located at Victoria Embankment Gardens, Thames Embarkment east of Charing Cross, London.

Above: In June 1918 the Camel Corps disbanded, (no longer useful for travelling until the end of the war). The troopers of Australian Camel Corps formed the 5th Light Horse.

The above memorial is in Melbourne – This small shrine is planted beneath a tree in Birdwood Avenue, Shrine Reserve, Melbourne. The tree was planted in 1934 by Captain J.R.Hall and was No.16 in the ballot.

There appears to be no substantial Memorial in Australia to the Imperial Camel Corps Australia WW1.

The Camels and their troopers have disappeared into the past!

There is no regimental history of the Imperial Camel Corp because as a regiment it did not exist. There were never any headquarters or organisations in Australia, other than the groups of originals who met up after Anzac Day.

Of all the fighting units in the British Army the Imperial Camel Corps are the least known to the general public throughout the Commonwealth, Britain, Australia and New Zealand.

They came from outback Queensland, Western Australia, Australia’s rural towns and cities, including many indigenous, from London slums and Britains’ stately homes. All classes of society and all types welded together by the incredible animal – the Camel.

Above: Kalgoorlie St Johns Anglican Church Honour Roll, Maritana Street, Kalgoorlie was opened 27 November 1921 by General Hobbs.

The inscription reads:

Gallipoli, Belgium, France, Egypt, Palestine

To the Glory of God

And in the memory of the gallant men of this Diocese who fought and fell in the Great War 1914-1919

The tablet is erected in pride of their valour and in sorrow for their loss

See Ye to it that they be ever held in honoured remembrance

Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori.

May they rest in peace

Amongst the names is Wilfred Roy TRENAMAN