The Importance of Burma for Japan

Showing main route of Britains retreat from Burma and Japan’s Advance – how it was necessary to repair airfields at Victoria Point, Tavoy and Ye and construction of Burma-Thai Railway would assist Japan’s conquest for Burma and India.

Burma would provide essential resources of rice, oil and wolfram (used in manufacture of tungsten for armaments) – however Japan’s strategic motive was to conquer Burma for several reasons-

To secure Japan’s newly won landward approaches to Thailand, Malaya and Singapore.

To cut Allied air route to providing essential arms, medicines etc into China by way of the Burma Road – more than 700 miles from Lashio, Burma to Kumning, the provincial capital of Yunnan, China and thus depriving Japan the opportunity to conquer all of China.

The above map shows the famous ‘Burma Road’ which the Allied Forces required to keep operating to supply China also ‘the Hump’ which Allied Bombing raids had to fly over from India. NB The ‘Burma Railway’ is not to be mistaken for Burma-Thai Railway.

The rough and mountainous section from Kunming to Burma border was built by 200,000 Burmese and Chinese labourers during Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and completed 1938. The British had used this road transporting materials to China before Japan was at war with Britain. Supplies would be landed at Rangoon (today known as Yangon) and moved by rail via Mandalay to Lashio, where the road started.

In 1940 Britain yielded to Japan to close down the Burma Road for 3 months. When Japan overran Burma the Allies were forced to supply Chiang Kai-Shek and the Nationalist Chinese by air. The US Army Air Force flew lend lease from airfields in Assamn, India over the mountainous ‘hump’ of the eastern end of the Himalayas.

‘Lend lease: Passed on March 11, 1941, this act set up a system that would allow United States to lend or lease war supplies to any nation deemed “vital to the defence of the United States.”

At this time: United Kingdom (and British Commonwealth), Free France, Republic of China, and later the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, and materiel between 1941 and August 1945.’

During March until July 1944 at Imphal, capital of Manipur, northeast India the Japanese Army suffered their first major defeat with heavy losses. It was the beginning of the end of Japan’s invasion and war in the Pacific. It was to be known as Japan’s worst defeat in history.

Under the command of British Forces made up of mainly Indian and British soldiers, the bitter fight to the end at mountainous Imphal – saw desperate hand to hand fighting, day by day and night by night. The Japanese attacked British troops across an asphalt tennis court and bomb damaged ruins of the surrounding small military base. Imphal remained British when they were saved by reinforcements. In particular, Indian troops gained recognition for their soldiering and bravery.

When finally defeated, Japan had lost much of its best army – Yamamoto Force, formed from units detached from Japan’s battle experienced 33rd and 15th Divisions under Major-General Tsunoru Yamamoto, commander of 33rd Division’s Infantry Group. The Japanese were without food and had little ammunition.

The Battle of Imphal took place in the region around the city of Imphal, the capital of the state of Manipur in northeast India from March until July 1944. Japanese armies attempted to destroy the Allied forces at Imphal and invade India, but were driven back into Burma with very heavy losses.

-

Rangoon, capital of Burma was of importance – Burma’s only seaport and a crucial link in the British air reinforcement route from India to Malaya and Singapore. These British airfields were Moulmein in the north, Tavoy, Mergui and Victoria Point in the south.

These four airfields were located on Burma’s Tenasserim Peninsula, a 500 mile long tail that hangs below Burma, sharing the Kra Isthmus with Thailand and Malaya.

With Japan’s expanding Pacific empire of occupying China, French Indo-China, Thailand, Malaya, Singapore, Hong Kong and the islands of Netherlands East Indies it was essential to take Burma to create a buffer zone to keep the Allies out of this immensely rich resources rich area – including oil, rubber and tin.

The British Royal Navy had lost its Singapore base and now Rangoon – restricting the Allies to operate out of Ceylon and Australia.

When Japan invaded Burma there was an existing railway line from Moulmein to Ye.

In Thailand there was a railway line from Bangkok to Banpong.

May 20, 1942: Japanese complete their conquest of Burma

August 1, 1943: Japan grants “independence” to Burma

‘A’ FORCE BURMA, GREEN FORCE NO, 3 BATTALION

Between September 1942 and July 1944 the Japanese sent more than 4800 Australian POWs to southern Burma. 800 Australians died.

‘A’ Force Burma – the first large work force to leave Singapore – 3,000 Australians as three Battalions with Brigadier Arthur Varley in command departed Singapore Harbour 14 May 1942 on two very dirty ‘junk’ ships – Celebes Maru and Tohohasi Maru sailing to south west coast of Burma. There was minimal space, drinking water was scarce and the rice and stew ration rarely reached the consistency of soup. There was diarrhoea, dysentery and bad latrines.

On the 17th a small sloop and two other ships carrying Dutch and British POWs and some Japanese troops joined the convoy off Medan on the east coast of Sumatra.

These three Battalions were offloaded at three places. On the 20th May Green Force and a medical and engineer detachment (1,017 in total) were dropped off at Victoria Point. On the 23rd May Ramsay Force (1,000 POWs) and 500 British troops from Sumatra were disembarked at Mergui.

Two days later the rest of the convoy reached the peninsula on the Burma coast near Tavoy.

Their first task was repairing/improving airfields left damaged by fleeing British. From the coast they would move to north end of Burma-Thai Railway to commence rail construction and meet with POW Parties working from Thailand.

‘The route of the railway line in Burma, though not as challenging in engineering terms as in Thailand, was remote and difficult to supply. It did not follow a river route and there was no good road. The work camps along the railway took their names from the kilometres that they were distant from Thanbyuzayat (for example, 55-Kilo camp).’

Please read Journalist Rohan Rivett’s published account of sailing to Burma

(Rivett was one of very few journalists to be taken POW)

Green Force began work at Kendau 4.8km Camp 1st Oct 1942. The first Australians to work on the Rail link.

In May 1942, the Japanese announced they required a

force of 3,000 men to be drawn from the 8th Division. Named ‘A’ Force, it was commanded by Brigadier A.L. Varley. This was the first Group of Australian POWs to depart Singapore, comprising Headquarters, Engineering and Medical Detachments, Battalions One, Two and Three.

It was drawn from 22nd Australian Brigade (under Brigadier Varley) 200 men from 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion (under Major C.E. Green) and 2/30th Battalion (under Lt.-Col Ramsay). Included was a medical group drawn from 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (under Lt. Col T. Hamilton).

Below: Lt Col Varley. He would later perish in a lifeboat after sinking of ‘Rakuyo’ Maru Sept 1944. He was elevated to CO 2/18th Batalion during battle of Singapore.

‘A’ Force was informed it would be sent to one destination.

The Japs refused permission to take any tools, medical supplies and other equipment, assuring the POWs that all these facilities would be made available at their unknown destination. Of course this was a lie.

The Force was landed at three different points, about 150 miles between each on the West Coast of Southern Burma. Victoria Point, Tavoy and Mergui. The Japanese would not permit communication between these groups.

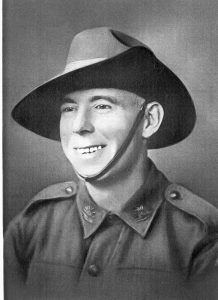

Green Force No. 3 Battalion was commanded by 2/4th’s Lt- Col. Charles Edward Green WX3435, who had become C.O. 2/4th MGB on the death of Lt.Col Anketell at Singapore.

60 men from 2/4th died – including 38 who did not survive in the South China Sea after their ship ‘Rakuyo Maru’ taking them to Japan, was torpedoed by American submarines 12 Sept 1944 and sank .

After repairing and constructing airfields, ‘A’ Force moved to Thanbyuzayat to work on the Burma end of the Rail Link.

On 14 May 1942 ‘A’ Force under the command of Brigadier Varley, embarked at Singapore on 2 ships with Headquarters, No. 2 and No. 3 Battalions on ‘Yoyohashi Maru’ and No. 1 Battalion and the medical detachment on ‘Celebes Maru’.

Near Medan, on the north east coast of Sumatra two small ships and a sloop transporting British POWs joined the convoy. They would be known as British Sumatra Battalion. Captured by the Japanese at Pandang, Sumatra they were moved north to Belawan, the port of Medan on 9th May 1942. Included amongst the ranks was Lt-Col Albert Coates A.A.M.C. – destined to become Senior Medical Officer on the Burma side of the rail link.

Please read further about Albert Coates

Green Force and 1,026 POWs disembarked at Victoria Point on 21st May.

14 December 1941 Japanese Forces take Victoria Point.

On 23rd May, Lt-Col Ramsay’s No. 1 Battalion & a British Sumatra Battalion disembarked at Mergui. As no prior arrangements had been made to accommodate Ramsay’s men, 1500 were housed in a school that could have comfortably provided room for 600/800 persons. (In Aug. 1942 Lt. Col Ramsay and his men were moved to Tavoy.)

Please read further about Lt. Col. Ramsay

The convoy’s remaining POWs, No. 2 Battalion under the command of Major D.R. Kerr of 2/10th Field Regiment disembarked Tavoy on 25th May. Lt- Col Varley also remained with No. 2 Battalion.

On arrival at Tavoy Lt-Col Anderson became Commander of No. 2 Battalion and Major Kerr his Second in Command.

From this point on the battalion was known as Anderson Force until its amalgamation with Williams Force on 3 January 1943.

Further reading on Williams Force

The men were set to work on runway repairs, extensions and roads at the aerodromes at all three locations for several months before moving north to Burma-Thailand railway.

Victoria Point 21 May 1942 – mid August 1942

Green Force was broken down into two groups. The first group comprising 600 all ranks were to work at the airfield camp – about 7 miles from Victoria Point town site.

The remaining 416 men in the second group were based at Victoria Point, accommodated in houses along the waterfront. Their work consisted of unloading aviation fuel drums and rice from ships, rolling, stacking and loading fuel drums onto trucks for the airfield and roadwork.

The Airfield group were accommodated in huts on the western slopes of a range of hills located on the eastern side of the airfield – about 1,000 yards north of the Japanese Garrison.

Major Green pointed out housing inadequacies and overcrowding. To alleviate the problem the men pulled down some huts around the airfield and rebuilt them at their camp. Improvements continued as the men settled into their new surroundings.

Towards the end of May work commenced on the airfield. The Japanese had grand ideas about improvements, but without equipment to carry out these tasks it would be impossible.

Unexploded mines were found and daily searches discovered a total of 4. The British, before they left following defeat by Japan, had damaged the runway before departing; leaving it pitted with craters which required filling before the airfield was serviceable. The total of 40 craters on the runway consisted of 11 small craters about 2-½ ft. in diameter and 6-8 feet deep. The 29 larger craters were about 25 feet in diameter and varied between 10 – 30 feet deep.

Other work consisted of levelling and rolling the runway, loading sand onto trucks, unloading and ramming sand, carrying sand in bags, filling bags, wiring the camp and roadwork.

Story of Pte Robert Goulden NX20420

At 1000 hours on 8th July 1942 Pte Robert Goulden NX10420 was reported missing. He was a cook and had transferred across to 2/4th so that Claude Webber could join his brother George who was also a member of 2/9th Field Ambulance. Goulden had made good his escape, however became lost and decided to surrender to Burmese Police. They handed him back to the Japanese.

He was returned to Camp and at 10.30 hours on 12th July was interviewed by Major Green. He told the Major he had been worried about his wife who had been sick. Goulden did not know his wife had given birth to his son Howard on 6th March 1942. Major Green pleaded Goulden’s case, explaining his anguish.

The Japanese insisted Goulden knew the rules governing escape and was executed by firing squad at 1200 hours, 12th July 1942. His execution was witnessed several including three men of 2/4th – Major Green, Lt. McCaffrey and Lt A H Watson.

Goulden’s death was used as an example of what would happen to POWs caught trying to escape. The irony was the Japanese firing squad honoured Goulden by presenting arms to his lifeless body before marching off.

Padre F.X Corry, 2/4th MG Battalion

conducted the funeral service at 1400 hours. Goulden was buried at Victoria Point cemetery, Lot No. 30, English Section.

From the end of July 1942, men from Victoria Point Camp started to arrive to help with working on the airfield. This indicated another move was afoot. By 10th August the airfield was being cleared of refuse, rollers moved and tools stacked away.

Tavoy-Ye-Lamaign-Moulmein

Green Force was now split into 2 detachments, the first under Major Green and the second under Major J. Stringer, 2/26th Battalion. From this point the 2 detachments leap frogged each other until they joined forces again at Kendau, 4.8km camp; the first construction camp on the Burma side of the rail link.

The first detachment left Victoria Point on 6th August arriving at Tavoy, three days later. They embarked on 2 ships, one with only the identification No. 593, being a small coal ship and the other ship named ‘Tatu Maru’.

The 15th August saw the initial draft of the first detachment leave Tavoy by truck, arriving Ye the same day. This was followed on 17th August by the remainder of the force in the second draft arriving at Ye the same day.

Work on the last and most northern of the three airfields was completed by mid September. All ranks, less the sick, marched out of Ye to Thanbyuzayat via Lamaign, over 25th and 26th September 1942, arriving at Thanbyuzayat on 28th September.

VICTORIA POINT – TAVOY

Conditions at Tavoy were much tougher than at Victoria Point – this is where the 2/4th first met with Dutch East Indies POWs.

1st Group was transported to Victoria Point to board a ship. Thus began the inevitable waiting around – but fortunately were given permission to visit local shops. Few had money and the frenzied shop proprietors tried to serve, return change and protect their stock!

When the POWs departed the shelves were almost bare – much was hidden in haversacks and on the bodies of POWs.

The men finally boarded two small ships (200-300 tons) one identified as No. 593 and the second ‘Taut’ Maru where the men were confined to the deck with little room except to stand or sit. The latrine was a frame slung over the side of the ship. Their only food supply for the next three days of rice bread was now turning mouldy.

The first night it rained heavily with the next morning fine with calm seas. Later showers returned and the seas became heavy resulting in many POWs being seasick.

Tavoy was situated at the mouth of Tavoy River, quite a distance from the coast. The POWs were ordered off the ship and onto steel barges which were towed by a tug up the inlet to where Anderson Force had been working for the past three months on the aerodrome. The Green Force POWs were about to join them.

They arrived late at the dimly lit HQ and saw what appeared to be foreign workers – wearing green European type uniforms with high peaked caps, talking in a language foreign to the Aussies! Initially they were thought to be Germans!

The next morning the newly arriving POWs realized they were Dutchmen from Java.

TAVOY

Conditions at Tavoy were much tougher than at Victoria Point and Mergui – where Ramsay Force disembarked.

TAVOY TO YE

Tavoy was to be Transit Camp for two drafts of 277 and 258 men from Green Force who on 15th and 17th August, moved to Ye further north on the Burma Coast. The trip can be described as a nightmare for some – all standing packed tight like sardines in an open truck at the mercy of some crazy Japanese drivers (obviously inexperienced) the speeding truck swayed side-to-side dodging pot-holes and careering around corners. The POWs were quite relieved and distressed on arrival.

Work on the aerodrome at Ye was completed by mid Sept 1942.

All ranks, less the sick, marched out of Ye to Thanbyuzayat via Lamaign over 25th and 27th September 1942 arriving on 28th September.

On 1st October 1942 all ranks of Major Green’s first detachment that left Victoria Point on 6th August marched out to Kendau 4.8km Camp.

Stringer’s 2nd detachment which left Victoria Point on 13 August aboard No. 593 ship disembarked at Tavoy. No. 583 returned to Victoria Point to transport the second and smaller draft – arrived Tavoy 15th August. They boarded Ukai Maru to sail to Moulmein on the Salween River.

Over 23rd and 24th August this group travelled by train from Moulmein to Thanbyuzayat. On 26 October 1942 Stringer’s detachment marched into Kendau 4.8km camp.

Green Force became united – Green Force now became No. 3 Battalion of the Burma Administration Group No. 3. – under the command of Japanese 5th Railway Regiment. Each POW was issued with a wooden plaque with his Japanese POW number inscribed into the wood.

Ye

Ye Camp have five special claims to fame –

It’s name

chanting monks

Howling dogs

‘Blue Danube’ soup

Dutch Dysentery Choir

The old English flavour of the name was applied to everything:

Ye Camp, Ye Toilet, Ye Jap, Ye Cookhouse, etc.

The large monastery in the town was filled with student monks who spent their whole day chanting religious verses at the top of their voices.

At night the village’s hundreds of stray dogs took over from the monks with their howling.

The very crowded Camp huts were filthy and vermin infected old native dwellings – between the monks and dogs came the marauding mosquitos at night to attack the sleeping POWs. Malaria increased.

The only vegetable supplied was eggplant. We were eating deep purple stew.

The Dutch Dysentery Choir originated from the Camp Hospital where there was a lot of sickness amongst the large party of Dutch POWs at Ye. The Dutch had suffered at Ye and to help raise morale they formed the Choir.

The beautifully harmonized Choir provided many hours of pleasure to the POWs.

The Japanese had been particularly ‘generous’ with their barbaric treatment of the Dutch – including stringing POWs up by their thumbs.

Tom Hampton of 2/4th wrote

“This was a bit too much for Jack Sherman from ‘A’ Coy. Finding one of the victims he cut the man down and assisted him to his hut. There was no immediate reaction from the Japs, they either didn’t see what happened or chose to ignore it so Jack lived to thwart them another day!”

Keith Griffith of 2/4th wrote

“About 8 Dutch Prisoners were tied around a tree with one long rope looped around each man’s knees with a slip knot round his neck. The tree was infested with large green jumping ants which were swarming over and biting the prisoners. They were continually bashed and as one man collapsed it would tighten the knot on the next man’s neck. A Japanese officer was present.”

The Green Force POWs remained working for about 5 weeks – mostly building a wharf.

Les Cody of “Ghosts in Khaki” wrote

“The men had by now adapted to a basic existence as POWs – the rice diet, living conditions and had learned to go with the flow on work parties with the Japanese. However they did not at any stage, surrender their personal independence.”

He wrote the story of a work party of about 20 men under Sgt. Brian Manwaring, 2/4th

“They were recovering logs from the jungle for piles and wharf decking. A bit of a character with a rather quizzical sense of humour Brian selected a log he thought would be eminently suitable for the job in hand and hooking on the chains gave the order …………. One, two, three, heave ………… one, two, three, heave……..

As the 20 straining men slowly emerged from the jungle, the Jap guard jumped to his feet in anticipation. With about 30 feet of rope attached to the log it took a while for it to appear and when it did the gang collapsed in exhaustion – it was about 6 feet in length and about the circumference of a small sapling. Brian looked at the Jap and in his quiet way said “yuroshi ka?” (good hey!)

The Jap looked at Brian, then ‘the log’ then at Brian, then at the men and then again at ‘the log’ and then exploded …… “Number One – Number One” and burst out laughing!

Not the reaction the men had expected they were taken by surprise and when the guard said “all men yasumei” (rest) the men couldn’t believe it!”

It never happened again. The story became a precious memory to share again and again in the dark days ahead. The Jap with a sense of humour!

‘A’ Force Burma was nearing the end of work on the airfields of south west coastal Burma. Their next work camp would be on the Burma end of the railway.

Ramsay Battalion from Mergui had by now joined Anderson Battalion and the balance of Green Force at Tavoy. Leaving Tavoy the Force moved by ship to Moulmien – then by road and rail to the small town of Thanbyuzayat – the starting point for the railway into Thailand. The exception was the Green Force contingent and a small group from Anderson Force at Ye who travelled overland.

The overland groups had a tough journey.

The bridges on the rail line from Ye to Thanbyuzayat had been blown. The POWs had to march 25 miles carrying all their gear, along the rough metalled line. The final 50 miles from the last broken bridge to Thanbuyuzat was by train in filthy cattle trucks with the POWs standing in inches deep manure.

On 1st October all ranks of Major Green’s first detachment that had left Victoria Point on 6th August marched out to Kendau 4.8 km Camp. The end of October drew nearer as did the end of the southwest monsoon. The men in Green Force would soon be hard at work constructing the rail link from the Burma end. Work had already begun on the Thailand side by a British work force.

Stringer’s 2nd detachment had left Victoria Point on 13th August aboard the ship No. 593. After disembarking the 1st detachment from Green Force, this ship returned to Victoria Point to transport the 2nd and smaller draft. This group arrived Tavoy on 15th August and on 20th August boarded the ‘Unkai Maru’ for passage to Moulmein for Thanbyuzayat. On 26th October Major Stringer’s detachment marched into Kendau 4.8 km Camp and Green Force was once again united.

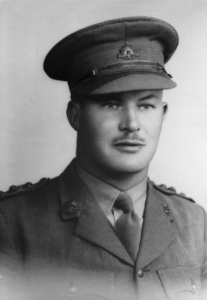

Below: Green at War Trials

Green Force became No. 3 Battalion of the Burma Administration Group No. 3, under command of the Japanese 5th Railway Regiment. Each prisoner was issued a wooden plaque with his POW number inscribed into the wood.

In October 1942 survivors from the HMAS Perth were shipped to Singapore from Java, and then to Burma. In October 1942, 385 Australians, commanded by Major L.J. Robertson, left Java on board ‘Moji Maru ‘; they joined up with A Force on 17 January 1943.

Between September 1942 and July 1944 the Japanese sent more than 4800 Australian POWs to southern Burma. 800 Australians died.

The railway line in Burma was remote and difficult to supply, especially during monsoon season when any existing roads became impassable. The roads were of poor condition and there was no river route to follow nor supply foods. In engineering terms, Burma was not as challenging as as in Thailand. The work camps took their names from the number of kilometres distant from Thanbyuzayat such as 55-km camp.

Please read more detail about Thanyuzyat, Japanese Admin and Base Camp for POWs.

Work consisted of felling trees, undergrowth clearing, excavating cuttings, building embankments and the construction of bridges across streams and gullies. At first when the railway route crossed reasonably easy territory the workloads were reasonable. By mid-1943 the construction pace increased, known as “Speedo” with some camps working shifts of 24 hours on and 24 hours off. The POWs were frequently subjected to violence from their guards, particularly the hated Koreans.

The Japanese administration in Burma was less efficient in Burma than Thailand. Supply difficulties increased as the railway advanced with monsoon season. By late 1942 the numbers of ill POWs increased because the lack of adequate food and medical supplies. Their condition worsened during 1943. The effects of malnutrition resulted in cholera, beri beri, dysentery, malaria and smallpox and tropical illnesses unknown to the POWs.

Quite early in the war the Japanese were exposed to Allied bombing. The Japanese denied POW leaders requests for Thanbyuzayat Hospital be marked as a hospital and POW camp. On 12th and 15th June 1943 by Allied bombing killed 23 POWs including 18 Australians. There were many more wounded.

WX9270 Thomas Joseph Fury died during an Allied air Raid on 15 June 1943. Aged 35 years, he had a wife and 3 sons.

Fury had left ‘Aquitania’ when it arrived Fremantle and was unable to reboard before the ship sailed for Singapore from Gage Roads, the following day 16 Feb 1942.

He became one of about 90 men from 2/4th to soon after be shipped out of Fremantle, but instead of disembarking at Singapore as planned, they landed at Java, joined the small number of Allied Forces and with ‘Blackforce’ prepared for the Japanese invasion a month later, inevitably becoming POWs on Java.

Fury was selected with ‘A’ Force Burma, Java Force No. 4 Williams Force for Burma, sailing via Singapore.

By October 1943 the railway was completed. During the next few months the POWs were moved south to Thailand. With evacuation of Thanbyuzayat many sick POWs walked to camps further up the line. Some had the dubious pleasure of travelling on the railway line they built. Some remained until 1944 cutting trees for fuel for the locomotives.

Despite the hardships, the death rate in Burma was not as high as some of the worst camps in Thailand. It is suggested the strong leadership of **Brigadier A.L. Varley and his relationship with the Japanese attributed to this. Varley cannot be written about without the great strength of ‘A’ Force’s officers and medical staff. (Brigadier Varley lost his liffe in the South China Sea following the sinking of ‘Rakuyo Maru’ September 1944).

**Lt-Col Anderson who became Commander of No. 1 Battalion was said by many to be the driving force behind Varley.

Lt-Col Ramsay read further about Ramsay.

Varley thought highly of Lt-Col Green. Please read further.

Of course ‘A’ Force cannot be written history without including the strength, skills and dedication of the doctors and their medical staff. Claude Anderson of the 2/4th, Albert Coates, Bruce Hunt just to name a few.

In October 1942 survivors from the HMAS Perth were shipped to Singapore, and then to Burma. In October 1942, 385 Australians, commanded by Major L.J. Robertson, left Java on board the Moji Maru ; they joined up with A Force on 17 January 1943.

MEILO CAMP (75km Camp) 28 March 1943 to 11 May 1943

In Burma the forward camp at Meilo (75km Camp) was home to over 2,000 Australians – moving the combined Green, Ramsay and Black Forces further into the jungle.

“The ‘75’ was a bad camp: it was at the peak of the speedo, the work load beyond endurance, the food ration cut to near starvation point and the never ending harassment. Time had degenerated into just a blurred sequence of pain when there was no beginning and no end to the day. Anywhere must be better than this,” wrote Les Cody, ‘Ghosts in Khaki’.

105km Camp (Aungganaung) 11 May to December 1943

The ‘fit’ men left ’75km’ on the 40km march in two drafts, many having just finished a 15-hour shift. The hungry, footsore men struggled through mud and jungle constantly harassed and driven for 3 days by the Japanese guards.

The sick were to be transported by truck.

A week later the Japanese Camp Commander Lt. Hoshi ordered 200 of the sick to begin the march. Another week later, a further 100 sick men were ordered to begin the march. “It was a shocking experience,” wrote Les Cody with men trying to support one another. The Japanese guards set a pace that resulted in the march degenerating into a shambles with men continually falling down and being forced to their feet with a boot or bayonet.

There was no drinking water and the POWs were forced to drink from the many streams they crossed. Cholera broke out. The death rate amongst these sick POWs accelerated rapidly during the next months.

They soon realized 105km was as bad as 75km. Fortunately the camp was located on a slope. The camp was not in ankle or knee deep mud. However there were frequent falls and injuries as they worked in the rain and mud.

The rain devastated the condition of what roads existed. They became seas of mud and men were diverted from rail to road work

With no machinery the only available material was timber – trees had to be felled (with blunt axes) stripped and cut to length, carried a long distance and laid 5 or 6 side by side for every metre!

The men were reduced to total exhaustion with shoulders, arms and legs numb and/or aching. Rations were scarce. Weevily, dirty rice cooked with melon or radish or turmeric. There was the occasional yak and the men searched for signs of grease on top of the soup.

Work on the line continued, pushing to meet the September deadline.

The Japanese demanding more and more men work. The POWs daily quota increased. From moving 2 ½ metres per day per man to 3 metres and finally 4 cubic metres per man per day. Work continued into the night by the light of bamboo torches. As the works extended, the trek back to camp became longer at the end of the day.

The roads from base had stalled. Engineers began diverting ballast from the track to fill holes. Men were required to carry heavy loads from the quarry by bag and pole or basket, along narrow muddy jungle tracks to the road. At ten loads per day, two men had moved more than a ton of metals over 10 kms and covered twice that distance.

Without transport rice parties were sent back to camps 20-30km further down the track. The loads were heavy.

Quarry work smashing and carting stone for ballast for the roads and stockpiles for the line lasted from dawn to dusk. The POWs were bootless and dressed only in ragged shorts or gee strings. Their unprotected bodies and limbs were covered in cuts and abrasions from flying chips of stone. The cuts and abrasions were then prone to tropical ulcers. The first sign of an infection would spark fear. Out of control 4th ulcer was capable of destroying a limb within weeks.

The only treatment for this scourge other than saline bathing was nightly scraping of the small ulcers with a sharpened spoon. The men would line up night after night at the ‘hospital’. There were no drugs and the pain excruciating and mates held the patient down whilst the Doctors scraped away the infected flesh.

Doctors and their helpers undertook the strain of inflicting such pain as above, the amputations, etc. without drugs as well as illnesses such as cholera.

The 2/4th’s M.O. Claude ‘Doc’ Anderson and his chief orderly Bob Ritchie had nursed the men all the way from Northam. Other M.O.s who used their added skills, knowledge and dedication to keep the men alive included Coats, Hunt, Dunlop, Moon, Corlette, Fisher, Hobbs, Krantz, Chambers etc.

“Together with the volunteers and orderlies the M.O.s wrote entirely new chapters into the manuals of care and dedication,” wrote Les Cody.

The POWs first turned to the Camp M.O. for protection and help during the grim days working on the line. And it is the names of the Doctors that are always spoken of by the survivors.

With increasing work pressure and hours, the rate of sick men escalated. The major base hospital at that time was Reptu (30km) and this raised the problem of either returning the sick to Reptu or alternatively sending up supplies to 105km for ‘the men who could not work’.

A ‘new’ hospital at 55km (Khon Khan) was to be no different from the other camps on the line. The same old decrepit bamboo huts, no facilities, no supplies and little food. The hordes of mosquitoes ensured malarial infection was rife.

Control of the camp was given to the senior Medical Officer, Lt. Col. Albert Coates who at that stage was seriously ill with scrub typhus at 75km camp. He arrived on a stretcher too week to walk and was carried around on it whilst doing his first rounds. The magnitude of the problem emerged when more than 2000 seriously ill men crowded into the sub-standard huts, which stood in the Camp mud and slush. With the concentration of sick at 55km, additional medical staff were brought up from base camps and transferred from working camps.

There were some 500 ulcer patients. The stench of the wounds and the continual sounds of pain penetrated all levels of the hut. Each patient dreading the verdict “it will have to be removed son”.

Coates carried out more than 120 major amputations between July and November. Of this number, 40 survived.

TAMARKAN CAMP – THAILAND.

Movement of men from Burma to base camps in Thailand began just prior to Christmas and continued for several months. The first to leave were the sick from Khon Khan, the 55km hospital to Nakom Pathon. Apart from maintenance gangs at 105km and small camps on the line back to Thanbyuzayat, all the POWs from Burma were cleared by March 1944, mostly to Tamarkan Camp, Thailand. Many of the sick died en route, their journeys often delayed and conditions harrowing.

Tamarkan was located at the southern end of the steel bridge over the Kwai Yai River. It was a dream camp in that there were vastly improved cookhouses and toilets. It had a canteen – most had little Japanese pay to spend (10 cents a day when on full work parades). Work parades were few, tasks were almost recreational servicing Japanese HQ, carting supplies of rice, wood and water for kitchens. The food was incredible! Thick and meaty stew loaded with vegetables and eggs and sufficient for seconds.

The physical transformation of the men began within a few weeks. The improvement extended to attitude. The pellagra sores caused by vitamin deficiency and the swollen limbs from beri beri began to disappear.

But this was not a change of heart by the Japanese – they wanted workers for Japan and healthy workers too. Some POWS were released for use in other areas of S.E. Asia but the Japanese wanted 10,000 of the most ‘fit’ men for general war production industries in Japan.

This selection for the Japan Party was entirely taken over and run by the Japanese. Those hospitalized with amputations, serious ulcers, skin complaints, malaria patients or were too old were excluded, including those who had dark skin (even freckles). 900 names of POWs were placed on that first list.

There were mixed reactions to the news. The POWs wanted to get away from jungle conditions, but were aware of US submarine attacks and had some knowledge of the progress of war via secret radios.

64 members from ‘A’ Force were included in the first party to leave Tamarkan for Saigon on their journey to Japan. Other parties were being assembled in base camps at Tamuang, Chungkai, Non Pladuck and Kanburi. Between April and June 1944, all Japan parties began leaving their camps for Saigon or Singapore.

From May 1944 onwards, the remaining POWs were sent back to Thailand’s jungle for various work parties.

Read Harry Pickett’s story of a POW on ‘Rakuyo Maru’ which was sunk in South China Sea and his rescue by USS ‘Pananito’.

Railway Construction Camps for Green Force

Kendau 4.8km 1 Oct 1942 to 1 Dec 42

Thetkaw 14km 1 Dec 42 to 28 Mar 1943

Meiloe 75km 28 Mar 43 to 11 May 43

Aungganaung 105km 11 May 43 to Dec 43

With the completion of the railway in December 1943, the Japanese began moving all POWs working in Burma, South to Thailand to one of 4-6 larger camps. These included Tamarkan and Kanchanaburi. They were mostly transported by trains on the track the POWs had themselves constructed and sabotaged! It was somewhat frightening during their train journey at times knowing their deliberate actions to undermine the stability of the rail.

The POWs were grouped into low-grade sick, very sick, etc. Those too ill to be moved remained behind with medical staff to care for them.

From Thailand the Japanese selected ‘fit’ POWs to be sent to Japan to work. (Many of these for the doomed ‘Rakuyo’ Maru Party). Those too sick to be selected remained convalescing in Hospital Camps and when sufficiently mobile made up work parties for various parts of Thailand.

Our Departed Comrades By Ted Murtagh, who worked on Burma end of Burma-Thai Railway with ‘A’ Force Burma, Green Force No. 3 Battalion (printed January 1999 Borehole Bulletin)

In the depths of southern Burma

Our departed comrades lay

Their grave there, marked by crosses

Beside the railway stay.

To make the hellish passage of those

Who passed that way.

They toiled, starved and suffered,

Our captors did not care

If we had no food or medicine

To fight disease with there

And when there came a small amount

They had the lion’s share

The doctors fought their hardest

And did their level best

To bring them through the darkness

To keep life in their breasts

But they went on their journey

And we left them there to rest

Comrades, left behind out there,

In our hearts will be

Your memory, till our race is run

And we meet up there with thee.

The following letter written by former POW Vern Roach from NSW mentions the friendship and nicknames of some of those with ‘A’ Force. See further